Understanding how and why students disengage or are starting to slide academically is especially important, given emerging findings from last spring’s national experiment with remote learning. In surveys, educators reported falling levels of engagement last spring the longer remote learning went on.

Unlike the other interventions in this series, an early-warning system doesn’t on its own help to re-engage students or fill in learning gaps. Like the lights on a dashboard telling you something’s wrong, an early-warning system uses indicators—missed days, falling grades, or a sudden rash of disciplinary actions—to identify which students need more help. And it provides a consistent framework district and school leaders can use to respond.

“It’s a nicely oiled machine, but it’s the seamless transitions from grade to grade and relationship building that really makes all of this work, so when you’re hit with a crisis, you can move and adjust,” said Jawana Akuffo, a middle school counselor in the White River school district in Washington state, about her school system’s robust early-warning system that spans both academic and social-emotional learning outcomes. “And by having that transition we can catch those kids who have fallen through the cracks.”

What indicators make up an early-warning system?

The purpose of an early-warning system is identification. The district selects a series of indicators—preferably ones that move in real time—that are statistically linked to dropping out, failing to complete major milestones in schooling, and other adverse effects. Generally, the indicators rely on data that districts should already be collecting.

District and school leaders are confronting difficult, high-stakes decisions as they plan for how to reopen schools amid a global pandemic. Through eight installments, Education Week journalists explore the big challenges education leaders must address, including running a socially distanced school, rethinking how to get students to and from school, and making up for learning losses. We present a broad spectrum of options endorsed by public health officials, explain strategies that some districts will adopt, and provide estimated costs.

Part 1: The Socially Distanced School Day

Part 2: Scheduling the School Year

Part 3: Tackling the Transportation Problem

Part 4: How to Make Remote Learning Work

Part 5: Teaching and Learning

Part 6: Overcoming Learning Loss

Full Report: How We Go Back to School

Then, districts create thresholds for each indicator that are consistent across all schools. For example, Johns Hopkins University, home to many of the researchers who have written on early-warning systems, recommends these thresholds for absenteeism at the high school level: Nine or more absences in a quarter indicate a student is “off track,” a student with five to eight such absences is “sliding,” and one with four or fewer is on track.

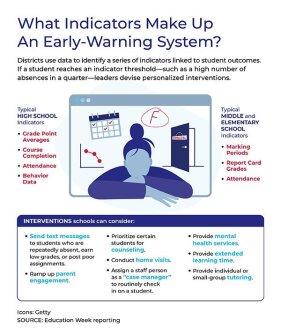

For high school, there’s widespread agreement about what should constitute the indicators: Grade point averages, attendance, course completion, and sometimes behavior data. Tests, it turns out, are not as predictive of dropping out at the high school level as the other combined indicators.

At the middle and elementary levels, attendance, marking period grades, and report card grades are often chosen. Districts have also added indicators they’ve validated on their own. Several districts in Montana, for example, found that mobility was predictive of future academic performance and incorporated that into their indicators, according to Sarah Frazelle, the director of early-warning systems for the Puget Sound Education Service District, in Washington state. Others have chosen 3rd-grade reading ability.

Above all, the system must be simple for educators to use. Indicator data should be compiled in an easy format for educators to review; some districts have hired third-party vendors to do that work, while others cobble together a user-friendly interface on their own.

“It should not be something that’s complicated; it should not be something that’s going to take a lot of extra time. Early-warning systems worked because they were very easy to understand and use so it’s not asking a whole lot in terms of people’s mental bandwidth for learning how to use this new system,” said Elaine Allensworth, the director of the Consortium on School Research at the University of Chicago, which has developed indicators for the Chicago Public Schools and produced many research reports.

What happens to students who are flagged under an early-warning system?

The key to success is what districts actually do when a student is identified. Sometimes intervention means a “light-touch” approach; students who trigger more flags in the system or don’t respond to initial efforts may need more-extensive help.

In the White River district, part of weekly professional learning community meetings is devoted to quickly reviewing the early-warning indicators and planning supports for any students they’ve flagged who need academic help. Support staff, counselors, and mental-health experts participate in weekly meetings too, just as teachers do, to review data on attendance, behavior, and social-emotional learning programming.

For example, at the secondary level, teachers on Monday review the academic indicators and academic targets for the week. If a student is having problems, a teacher goes into the student’s online planner to reserve “Hornet Time” or “Grizzly Time,” periods named after the schools’ mascots. During these 30-minute periods, which are worked into the master schedule on Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays, students work with the appropriate teacher to master the specific missing skill or content. (They don’t miss out on regular grade-level teaching.)

Other interventions schools can consider, listed in order from lighter-touch to more intensive, include:

- Having a teacher send text messages to a student, if he or she is absent several days in a row or earns low grades on assignments.

- Ramping up parent engagement, for example by notifying them of homework assignments and quizzes.

- Prioritizing certain students for counseling.

- Conducting home visits.

- Assigning a staff person as a “case manager” to check in on a student several times a week.

- Providing mental health services.

- Providing extended learning time.

- Providing individual or small-group tutoring.

Finally, once the district has intervened with a student, it needs to follow up over time to see if the extra help is making a difference, or whether further assistance is necessary.

Do early-warning systems work for all students?

The research on the systems in high school is solid, concluding that they are better than test scores for identifying which students are at risk of dropping out. High school GPA seems to be an especially powerful indicator.

But the evidence is sparser on other populations. (One study of English-language learners found that early-warning indicators didn’t do a good job of identifying newcomer ELLs who would later go on to drop out.)

There’s generally less research evidence about how to structure early-warning systems at the elementary level, where grading is less emphasized, though many districts have adapted them for those grades as well.

The COVID-19 pandemic raises new questions and challenges for early-warning systems. Certain indicators like attendance take on new meanings, and the White River educators say they are contemplating how to keep the tenets in place as they transition to remote learning. One idea is reserving some in-class time at school for small group interventions; another is learning how to spot new clues that students may need more help.

“How do you find that right balance of online instruction with students interacting with the teacher and with one another from an engagement level, and how are we going to measure it? Maybe it means tracking who is showing up, and who, when we get on a Zoom meeting, always has their camera turned off. Or who isn’t eating well, or isn’t very well kept, or who is saying, ‘I can’t show up to algebra because I have to work,’” said Cody Motherhead, the principal at the district’s high school.

Putting It All Together

Districts will need to be creative about the attendance indicator.

Attendance is one of the most basic data points every district collects, and a core element of early-warning systems. But in a remote setting, the notion of attendance has taken on a myriad of new meanings.

Some districts are now looking at whether students are logging into the synchronous portion of instruction or filling in a shared spreadsheet on attendance. The problem with those measures is that they don’t say much about engagement. Researchers suggest a more useful gauge could be tracking whether they are completing assigned work.

“I think that what they will have to track is assignment completion. Anything else is going to be really tricky—all the data about whether students are logging in and how long are they on, a lot of times that’s not very good data,” Allensworth said.

Plus, assignment completion has the advantage of being workable across both remote and in-person contexts.

Involve a broad section of leadership in the development of indicators and deployment of interventions.

Amassing, disseminating, and interfacing with the data that powers the indicators can be a challenge, noted Frazelle. Information technology directors sometimes know where data live and can help connect disparate data sets; larger districts can bring their research teams to bear on the problem.

Above all, when you plan interventions, don’t put the responsibility solely on the counseling staff to respond; it’s already overburdened in most districts, she noted. Instead, think about who else could participate and receive training on interventions, including paraeducators, teacher-leaders, or teachers on special assignment.

Similarly, the systems only truly work through a combination of bottom-up and top-down buy-in. Superintendents need to support the data collection and reporting, but it’s the teacher teams and cross-sector communication that makes the interventions happen.

Don’t neglect social-emotional learning.

Isolation, lack of face-to-face contact, and other new challenges wrought by COVID-19 mean it’s critical to make an early-warning system responsive to SEL needs.

In White River, at the elementary level, the district uses a screener to examine behavior concerns, both externalized (theft, quarreling) and internalized (withdrawn, being bullied). Teachers fill it out three times a year and schools’ teams use the data to plan. And the district provides special SEL programming in the difficult transition years of 7th, 8th, and 9th grade.

The City Year tutoring program, which deploys AmeriCorps volunteers in schools in nearly 30 cities, uses early-warning data to prioritize the students it works with. Part of its intervention relies on involving students in goal setting and recognizing those students when they’ve met goals for attendance or behavior.

“There is some agency that I think is magical, when an AmeriCorps member can facilitate the student articulating for themselves what they need and what they believe can help them be successful to improve their academic performance,” said James Ellout, the managing director of impact for City Year Jacksonville in Jacksonville, Fla. “And they feel heard, and it’s really great to see.”