Corrected: High school student Ameera Patel is multiracial. She has black and white ancestry as well as Indian.

Schools in the ‘new’ South Africa are shouldering the burden of developing future leaders to unite a nation fractured by apartheid.

“Too many white people,” Junior Nyola declares with a shrug, after joining a group of white teenagers hanging out in their high school auditorium.

Nyola is black, and so far, of the black students gathered here at H.F. Verwoerd High late this afternoon, he’s the only one to approach the white boys.

Then, the lanky 18-year-old jokes: “They’re like black guys, these guys.”

The white boys blush and burst into laughter, shoving each other as Nyola smiles broadly.

More teenagers from two other area schools trickle into the auditorium, gathering in clusters with their friends and inevitably within their comfort zones: blacks with blacks, whites with whites, Indians with Indians. Handpicked by their teachers and principals, they’ve come to Verwoerd High for an interpersonal-communication workshop intended to foster ties among students of varied races through art.

Teens scribble their names on white stickers, as rock music laced with pulsating African rhythms sends vibrations rumbling through the room. Corralled by the workshop organizers, the students march in a circle gyrating to the beat. All the while, a blend of pleasure and anxiety shows on their faces.

Questions abound: How do their counterparts of other races live? What does their school look like? Will they like me?

Normal teenage angst? Maybe. But digging deeper within every hug and handclap, these young men and women yearn to demolish the racial barriers that kept their parents apart in the South Africa of old.

A decade ago, it would have been rare, if not impossible, for students of different races to learn and laugh together. Laws, beliefs, and hatred would have separated most of these students, deepening their distrust and dislike for one another.

For many of them, 1994—the end of apartheid—is history. They want to move forward and distance themselves from their parents’ South Africa, to shape a country based on understanding and unity.

“The way my father was raised ... you won’t be able to change his mind,” admits Robert Boshoff, an earnest, 16-year-old Verwoerd High School student who is white.

Many are indeed counting on these young men and women to lead the new South Africa. But the deep scars of apartheid have ravaged the very schools charged with equipping them with the knowledge—academic and cultural—to transform this nation of 40 million.

‘I had to show them that I have a right to be in school.’

After a lengthy struggle to open schools to all children regardless of race or ethnicity, the battles these days have shifted to focus on improving the quality of education, raising students’ dismal test scores, and renovating dilapidated classrooms. Within that effort exists a strong emphasis on values and human-rights education to ensure that South Africa doesn’t revisit its racist past.

“To a certain extent, we have achieved universal access to education,” says Duncan Hindle, a deputy director-general for the national Department of Education, here in Pretoria, South Africa’s administrative capital. “The big question is, access to what? Clearly, the legacy of a divided system is still with us.”

A debate also is brewing about how to proceed: equality or equity? Equality is the principle that the same level of public resources should be distributed to every school, says Bobby Soobrayan, another deputy director-general for the Education Department. The South African government is currently taking that direction.

Equity is closer to the American concept of affirmative action, giving more resources to those who were oppressed and exploited, Soobrayan explains. Public pressure has been increasing for the government to place a greater emphasis on this policy approach.

Since South Africa’s market-driven economy has yet to yield additional money to improve the schools, little is left after equalizing the education budget to give extra help to disadvantaged schools. Some believe education funds are being mismanaged because school systems lack the capacity and knowledge to spend money efficiently. Others argue, however, that South Africa—one of the continent’s richest nations—is misdirecting its funds, particularly by giving an excessive share to the military.

“That’s a political question,” Hindle says in response to such charges. “I’m not going to answer that.”

While the odds appear overwhelming, Soobrayan points out that the new, black-led government has been in power for only eight years. In that time, the system governing the nation’s 11 million students and 27,000 public schools has been rebuilt from the ground up.

“Eight years,” Soobrayan stresses, “is a very short time.”

The United States, after all, has been tackling school integration, with mixed success, for almost 50 years, since the landmark 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka that ordered legally separate schools to desegregate.

But the racial makeup of South Africa’s population—roughly 10 percent white and 90 percent black, Indian, and “colored"—creates a completely different set of dynamics from those in America. (South Africans use the word “colored” to describe people who are of mixed racial descent. It is not considered a derogatory word.)

Given the overwhelming nonwhite majority, people here say, it’s impossible to integrate South Africa’s black children into the country’s historically advantaged schools, which previously served only white children. And white parents certainly aren’t sending their children to the long- neglected, deplorable schools that most black children attend.

Although South Africa is making headway in improving education conditions, a 2000 government report showed that a third of the nation’s schools had “weak” or “very weak” buildings. Almost half of all schools had no electricity, while close to a third had no access to water.

Still, as South Africa works through its human- rights and economic challenges, schools here have no choice but to shoulder the burden of teaching its future leaders to embody the country’s new vision.

How the nation will ensure that schools have the tools and the teachers have the training to achieve those daunting goals is uncertain.

‘When you're white, and you stay with whites all your life, you can't walk up and talk to blacks. You're afraid. What do you say?’

Rusted clouds of barbed wire, foreboding gray cement-block walls, or black iron bars topped with crown-like spikes surround practically every school, home, and business in Gauteng (pronounced How-tang) province, which includes Pretoria.

Because of the high rates of crime and violence, most describe the barricades as necessary protection to keep criminals out. Yet those same devices also keep people apart.

It’s this isolation that feeds into fear and mistrust. South Africans of all races live in this province, but somehow they exist in different worlds.

Diepdale High School in Soweto sits in one of these communities, amid a sea of “matchbox” houses that are characteristic of this poor township of more than 500,000 people. The cramped, four-room homes are made up of a kitchen, dining-living room, and two bedrooms. An outhouse stands in the back yard of many of these homes, but at night, it’s sometimes too dangerous to go outside. A bucket in the house serves as a makeshift toilet.

During a break between classes, Diepdale High’s 720 students, clothed in pilling chocolate-brown sweaters trimmed with gold stripes, scatter. Some girls head to the bathroom. Holes in the sink basin mark where faucets should be. The toilets are clogged with waste and used feminine products. Discarded newspaper substitutes as toilet paper.

In the schoolyard, students drink water from a tap on the side of a school building. Boys and girls at the all-black school kick up the reddish dirt that surrounds the campus, creating a dusty haze.

|

| Missing hardware transforms toilets at Diepdale High into waste receptacles. Students at all-black schools have only outhouses. —Karla Scoon Reid |

No need to venture into the library for a book. It’s a mere shell, with bookshelves warehousing useless and outdated books and materials. Pages ripped from books are strewn throughout the room, waiting to be recycled.

Cooking instruction is canceled, too; someone stole the stoves.

Back in teacher Thanyani Ramalata’s classroom, wires dangle from missing light fixtures in the ceiling. Without electricity, there’s no heat during the chilly winter season and no air conditioning in the steamy summertime.

The barren environment doesn’t detract from Ramalata’s economics lesson, though. Her senior students energetically debate South Africa’s economic policies, using local newspaper articles because they don’t have enough textbooks. The students here know that other schools have nicer classrooms and an abundance of books, as well as electricity. They don’t dwell on their disadvantages.

“Really, we have one thing in common,” Diepdale student Daphney Mabaso emphasizes. “That’s education.”

Mabaso and classmate Rirhandzu Gezani spent a week at Greenside High, a school with a multiracial enrollment, to attend classes and live with students’ families in a diverse middle-class suburb of Johannesburg.

“I was scared,” Gezani, 18, acknowledges, looking down at the floor. “I didn’t know if they would treat me well or not.”

|

| Teacher Thanyani Ramalata has only ripped-up books in the library at Diepdale High School. —Karla Scoon Reid |

Instead, the girls say the Greenside students’ parents treated them like their own children. Mabaso and Gezani were impressed that Greenside High parents communicate with their children’s teachers regularly and visit the school often. Students there must participate in sports.

The girls were part of a student-exchange program called Reach Out and Build Friendships, or R&B, run by AFS Interculture South Africa in Johannesburg.

AFS, an international nonprofit organization, normally hosts student-exchange programs between countries. But Teddy Boyi, an AFS coordinator who grew up in Soweto, realized the program’s premise could work in Johannesburg between black students living in poor townships and students living and attending schools in the suburbs.

With its goal of exposing myths and misconceptions between cultures and encouraging understanding, the R&B program also hopes to broaden students’ knowledge about South Africa. Many teens here live in racially isolated communities, never venturing far outside those borders. “We’re trying to show young people the realities in our country,” Boyi says.

‘The difference is the color. We are the same.’

A sweet perfume envelops visitors to Greenside High School’s lobby in this Johannesburg suburb. A sign propped up behind a huge bouquet of colorful flowers celebrates the school’s near-perfect senior-exam pass rate of 99.45 percent. Framed photographs of the school’s top students line one wall.

Roughly 1,000 students of every complexion bound around campus dressed in suit coats of Kelly green and lipstick-red and emblazoned with the school’s embroidered crest. Their school bags bulge under the weight of textbooks, papers, and projects.

The library boasts an impressive array of books, but students likely opt to surf the Internet in the computer lab instead. To stay fit, students can swim laps in an Olympic-size pool.

On a warm and sunny September afternoon, four girls gather under the branches of an imposing tree on Greenside’s immaculately landscaped campus to recall their week living in Soweto and attending Diepdale High School.

One word sums up Ameera Patel’s experience: “Unbelievable.”

A young child in the Soweto neighborhood cried out of fear upon meeting 16-year-old Sarah Godsell, a fair-skinned blonde.

“I didn’t expect to be the only white person,” Godsell says.

The others are quick to chime in, talking over each other about their observations of Diepdale. The teachers were loud and authoritarian. One science teacher was brilliant, despite having scant equipment and books for instruction.

“They do everything in standard grade,” explains Lauren Van der Westhuizen, a white 16-year-old. “They can’t get into university with only standard grade"—a lower-level class.

But you can’t feel sorry for Diepdale’s students, says Patel, shaking her head.

“Just because they don’t live in a big house doesn’t mean they’re not rich,” she contends. “Their family environment is so rich.”

Overall, all four girls agree that students in Soweto were friendlier to them than their Greenside classmates were to the girls who visited their campus. They’re not sure why.

‘Old, black people are not bitter. Old people of other races are not as forgiving.’

One of Pretoria’s most desegregated schools also happens to be named in honor of Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd, the man many describe as the architect of apartheid. The late prime minister, who was assassinated in 1966, is credited with strengthening racially divisive policies that denied blacks access to jobs and education.

Rich green shrubs in front of the school surround an imposing cement bust of Verwoerd (pronounced Fer-voort). The deputy principal gathers a group of white and black girls around the statue, asking them to arrange themselves: black, white, black, white, and so on.

“Show how diverse this school is, girls,” Fanus Pienaar pleads. The girls giggle and willingly toss their arms around each other, mugging for the camera.

Reluctantly, Pienaar breaks down the school’s demographics: About half its 737 students are white, while the remaining students are black, Indian, or colored. “We don’t speak of blacks and whites here,” Pienaar says, because race is such a divisive issue.

|

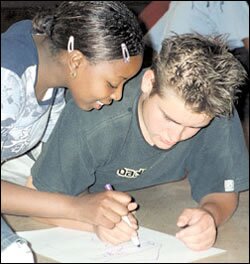

| Students share a marker to draw their dream house during a workshop at H.F. Verwoerd High School. Some participants in the workshop, which brought together black, white, and Indian students, had never before touched a member of another race. —Karla Scoon Reid |

The school opened its doors to black students in 1994, starting with the 8th grade, and added a grade each year until the school was desegregated. While South African law forbids using race to deny a student’s enrollment, no national school desegregation policy exists.

Pienaar says Verwoerd High wanted to control the pace of integration to avoid racial conflicts that had erupted at a few other schools. In the past eight years, Pienaar proudly reports, very few student fights could be linked to race.

“If the whole of South Africa could control racial harmony as we do,” he says, sighing, “this would be a wonderful country.”

The shades and hues of faces streaming by in the hallways between classes show that Verwoerd High is indeed desegregated. But in the classroom, students are divided based on their languages of instruction, which local school officials determine. Most black students, who speak African languages at home, choose to study in English. Most white students prefer to be taught in Afrikaans, a language unique to South Africa that grew from the first Dutch settlers and was influenced by the English, German, French, Malay, and Hottentot-Zulu languages.

Language is a particularly sensitive issue. The apartheid government forced black students to learn Afrikaans in the mid-1970s, leading to violent protests.

It’s a common pattern played out in schools across South Africa. Blacks see English as the language of economic and political power, while Afrikaners want to preserve their language and history, in addition to learning English. South Africa has 11 official languages.

Verwoerd High tries to bridge the language divide by teaching art and other electives in English so that students can take classes together. Socially, however, students tend to hang out with those who speak their home languages, and ultimately, are of the same race, Pienaar concedes.

While Mara du Toit teaches her algebra lessons in English, most of her students are black and whisper to each other in the melodic Zulu or another African language. When the public-address system crackles with a reminder from the office, it’s in Afrikaans.

Without skipping a beat, du Toit translates the announcement for those who may not understand. She hands out the latest graded test, encouraging some and scolding others who didn’t put forth their best effort. After class, she says that the cultural and language barriers aren’t a factor in teaching math.

“I don’t think in English or Afrikaans. I think in math.”

Still, this schoolby its very name is a contentious place, says Colyn Schutte, the head of policy and planning in the Gauteng education department’s Tshwane North District. So it’s almost “prophetic,” he says, that Verwoerd is progressing on the right track while other schools flounder.

Yet Schutte, a burly, outspoken man, notes that Verwoerd High was losing enrollment in the mid-1990s and had little choice but to enroll black children or face empty classrooms.

“We have to be brutal about it,” he says during a recent visit to the school. “Would [the school] have come this far if the enrollment numbers had stayed constant?”

‘We as blacks put ourselves down most of the time. Whites would accept us the way we are if we let them.’

The auditorium at Verwoerd High is filled with soothing sounds for the communication-in-diversity workshop. Students—Indian, black, and white— from Lotus Gardens and Makhosini high schools, along with Verwoerd’s, lie on the floor with their legs and arms spread wide apart. Their eyes are closed.

Christo Potgieter, a teddy bear of a man dressed in black, roams barefoot around the room speaking in a reassuring, almost priestly tone. Potgieter, who is white, aims to guide the teenagers to a stress-free center within themselves.

“You can cope. You are safe, and you are accepted by everybody in this group,” he coos in English tinged with an Afrikaans accent.

The workshop, designed and run by Pot-gieter and his partner, Esther Bredenkamp, is offered by the nonprofit arm of their interpersonal- communication and life-skills-development firm, Comskill. More than 2,000 students have participated in these educational programs, which they had to stop offering regularly after their funders went bankrupt.

Once the youths’ bodies go limp, the relaxation exercise is over, and it’s time to make music. The students grab drums, finger cymbals, sticks, and triangles.

After prompting from Potgieter and Bredenkamp, they compose an infectious, percussion- laden song punctuated by rhythms patterned after syllables in the phrases “I am magnificent” and “Change your attitude.”

“I get so frustrated with what’s happening in our country,” says Hennie du Toit, Verwoerd’s principal, watching the informal concert. “And you look at this. ... If you put your heart in it, it can work.”

Later, huddled in small groups, the teens discover that a black student wishes pizza could be served for every meal, while a white student is a rap-music fan. Seemingly uninspired conversations like these, and role-playing games, help shatter cultural barriers and build relationships.

The participants are instructed to each pair up with a student from another school (and especially another race, if possible), to draw a “dream house” together, using a single marker. Each two-person team must hold the marker together.

Boys and girls who were once rigid and a little resistant start loosening up. Hands, arms, legs are touching—in some instances, for the first time with a person of another race. Bredenkamp, a statuesque white woman with dramatic eyes deepened by dark liner, surveys the partners’ work and whispers, “This is very hard for them.”

Using an approach that they call “sound-voice-movement,” Potgieter and Bredenkamp, who have extensive drama backgrounds, encourage students to explore their beliefs and attitudes to help them reach a greater understanding of diversity. Because the teenagers are so culturally divided, they begin with the benign similarities they share—food and music, for example.

“Some way, we’ve got to get people to trust each other,” implores Bredenkamp, a former early-childhood educator.

But the drums, dancing, and chitchat can’t mask how sensitive and profound this experience can be.

Still, the process is exceedingly slow.

Being accepted by a white person, someone who still is considered part of South Africa’s elite social class, is seen as an achievement for blacks, notes Guilty Maaga, a law and business teacher at Lotus Gardens High School. The nation’s old social order started with white people at the top, followed by Indians, colored people, and then finally, blacks.

For some white and Indian children who have grown up with blacks cleaning their homes and cooking their meals, they see little benefit in associating with blacks, Maaga says, during a break from the workshop.

Even in the classroom, Maaga acknowledges that some of his Indian students accept him as their black teacher, yet they won’t accept other blacks.

As the diversity workshop at Verwoerd High draws to a close with one last dance, no one wants to leave. Hugs and telephone numbers are exchanged. Promises are made to meet again.

“I’m astonished that we could work together in that way,” Pieter Marais, 15, a white Verwoerd student, says with a thick Afrikaans accent.

Teenagers describe how black students who befriend white students are teased and called “Oreos” (black on the outside and white on the inside). Indian students say some worry that “blacks will rule you” as they become the majority in schools. Some boys and girls say their parents forbid children of other races to visit their homes. And others voice concerns that the black majority, now that it has political power, is starting to oppress whites.

But it’s not hopeless, assures Brenda Maseko, 18, a student at Makhosini High, a predominantly black school near Pretoria.

“The more of us that can be together ... the more contact we have with one another,” she says, beaming, “we’ll finally feel comfortable together—all the time.”

After all, they’ve promised to meet again one day. That’s a start.

Coverage of cultural understanding and international issues in education is supported in part by the Atlantic Philanthropies.