“We’re going to treat PARCC and Smarter Balanced like any other vendor,” Mr. Holliday said.

The Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers released pricing that’s just under the $29.95 median spending for summative math and English/language arts tests in its 19 member states. That means that nearly half of PARCC states face paying more for the tests they use for federal accountability.

The Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium, or SBAC, the other state group using federal funds to design tests for the common standards, released its pricing in

Georgia Drops Out

States at various points in the cost spectrum reflected this week on the role that the new tests’ cost would play in their decisions about how to move forward. Within 30 minutes of PARCC’s announcement on July 22, Georgia, one of the lowest-spending states in that consortium, withdrew from the group, citing cost, along with technological readiness and local control over test design, among its reasons.

The cost of the tests being built by PARCC and Smarter Balanced are a topic of intense interest as states shape their testing plans for 2014-15, when the consortium-made tests are scheduled to be administered. Building support for different tests can be difficult even without a price increase. But that job is even tougher when new tests cost more than those currently in use.

SOURCES: PARCC, Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortia

“I’m not going to suggest to you that it’s an easy sell to the legislature,” said Deborah Sigman, the deputy superintendent who oversees assessment in California, which belongs to the Smarter Balanced consortium. “But we think that assessment should model high-quality teaching and learning. To do that, you have to look at assessing in different ways.

“The irony is, people say they want a robust system that gets to those deep learnings, but let’s make sure it doesn’t take as much time and that it doesn’t cost more money. Those things are incongruent. Those performance items require more resources and a greater investment.”

California faces a steeper assessment bill if it uses Smarter Balanced tests, Ms. Sigman said. The state’s lower legislative chamber has passed a measure embracing those tests, but the Senate has yet to act on it.

Douglas J. McRae, a retired test-company executive who monitors California’s assessment movements closely, believes the SBAC test will cost the state much more than current estimates suggest. Testifying before the legislature, he said that assumptions about cost savings from computer administration and scoring, and from teacher scoring, are inflated, and that the real cost of the test there could be closer to $39 per student.

Different Models

While PARCC’s pricing offers just one fee and set of services, Smarter Balanced offers two pricing levels. It will be responsible for providing some services, such as developing test items and producing standardized reports of results, and states are responsible for others, including scoring the tests. Smarter Balanced states could opt to score their tests in various ways, such as hiring a vendor or training and paying teachers as scorers, or combining those methods. SBAC will design guidelines intended to make scoring consistent, said Tony Alpert, the consortium’s chief operating officer.

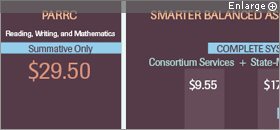

Smarter Balanced’s cost projections include what states pay the consortium for services and what they should expect to spend for services they—or vendors—provide. For instance, the $22.50 cost of the “basic” system is made up of $6.20 for consortium services and $16.30 for state-managed services. The $27.30 cost of the “complete system,” which includes interim and formative tests, breaks down to $9.55 for consortium services and $17.75 for state-managed services.

In PARCC, the consortium, rather than individual states, will score the tests, according to spokesman Chad Colby. PARCC’s pricing includes only the two pieces of its summative tests: its performance-based assessment, which is given about three-quarters of the way through the school year, and its end-of-year test, given about 90 percent of the way through the school year.

Its price does not include three tests that PARCC is also designing: a test of speaking and listening skills, which states are required to give but don’t have to use for federal accountability; an optional midyear exam; and an optional diagnostic test given at the beginning of the school year. Pricing for those tests will be issued later, according to Mr. Colby.

Paper-and-pencil versions of the PARCC tests, which will be available for at least the first year of administration, will cost $3 to $4 per student than the online version, according to a document prepared by the consortium.

A Value Proposition?

State spending on assessment varies widely, so states find themselves in a range of positions politically as they anticipate moving to new tests.

Figures compiled for the two consortia’s federal grant applications in 2010 show that in SBAC, some states paid as little as $9 per student (North Carolina) for math and English/language arts tests, while others paid as much as $63.50 (Delaware) and $69 (Maine). One state, Hawaii, reported spending $116 per student. In the PARCC consortium, per-student, combined costs for math and English/language arts tests ranged from $10.70 (Georgia) to $61.24 (Maryland), with a median of $27.78.

Comparing what one state spends on tests to what another spends—and comparing current spending to what PARCC or Smarter Balanced tests could cost—is difficult for many reasons. One is that states bundle their test costs differently. Some states’ cost figures include scoring the tests; others do not. Some states’ figures include tests in other subjects, such as science. Some states’ figures lack a subject that the two consortia’s tests will cover: writing.

Most states’ tests are primarily or exclusively multiple choice, which are cheaper to administer and score. Some give more constructed-response or essay questions, making the tests costlier to score but of greater value in gauging student understanding, many educators believe.

Matthew M. Chingos, a Brookings Institution fellow who studied state spending on assessment last year, said he is not yet sure the consortia’s pricing will prove accurate.

“What are these numbers based on? There’s no way for anyone to verify the work yet,” he said. “People need to be skeptical of anyone who says they know what this is going to cost until [the consortia] are further down the road.”

Edward Roeber, a former Michigan assessment director who is now a consultant for various assessment projects, said he is concerned that states that choose to withdraw from consortia work now face paying more to develop tests on their own because they won’t benefit from the economies of scale that consortium work can offer. That added cost down the road, he said, could lead states to buy cheaper, less instructionally useful assessments.

The two consortia are keenly aware that states might find it difficult to win support for the new tests if they represent increases in cost or test-taking time. They are taking pains to point out what they see as the value their tests will add compared with current state tests.

A PowerPoint presentation assembled by PARCC, for instance, notes that its tests will offer separate reading and writing scores at every grade level, something few state tests currently do. It says educators will get results from its end-of-year and performance-based tests by the end of the school year, while in many states, it’s common for test results to come back in summer, and even, in some cases, the following fall. Echoing an argument its officials have made for many months, the PARCC presentation says that its tests will be “worth taking,” since the questions will be complex and engaging enough to be viewed as “extensions of quality coursework.”

It also seeks to make the point that $29.50 isn’t a lot to spend on a test, noting that it’s about the same as “a movie date” or “dinner for four at a fast-food restaurant,” and less than what it costs to fill the gas tank of a large car half full.

Mr. Alpert of Smarter Balanced noted many of the same points, as well as the “flexibility” of SBAC’s decentralized approach to scoring and administration, which offers states many options for how much to do themselves and how much to have vendors do. If states choose to draw heavily on teachers for scoring, he said, they derive an important professional-development value from that.

“Comparing costs isn’t really accurate,” he said. “States will be buying new things. It’s like comparing the cost of a bicycle to the cost of a car. A car costs more, but what are you buying? [Smarter Balanced tests] are definitely a better value and a better service. They’re going to give teachers and policymakers the information they’ve been asking for.”

The role of artificial intelligence in scoring tests remains an open question in both consortia. If they determine that it is reliable enough to play a large role in scoring, test costs could decline.

Quality Versus Cost

In Massachusetts, cost isn’t the most important factor in looking ahead to new tests, since the state currently spends more than the PARCC tests are projected to cost, said education Commissioner Mitchell D. Chester.

“The number one criteria for us is the quality of assessment and whether it represents a value proposition beyond our own assessment,” he said. “If [PARCC tests] show that they’re at least as strong in terms of the expectations for student performance, and that they measure a broader range of academic skills, that’s the threshhold decision for me.”

The PARCC tests will demand more extensive tasks in math, and more writing and research tasks, than does the state’s widely regarded MCAS, Mr. Chester said. He said PARCC would prepare students for college better than the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System. Currently, he said, four in 10 Massachusetts students who enroll in public universities require remediation, even though the “vast majority” have scored “proficient” on the MCAS.

That is a poor reason to switch assessments, according to Jim Stergios, the executive director of the Pioneer Institute, a Boston-based group that has been among the common core’s most vocal critics in Massachusetts. The solution, he said, is to raise the cutoff score on the MCAS, something the legislature has “lacked the political will” to do. Mr. Stergios and other critics contend the common assessments are flawed because they rest on standards that emphasize nonfiction at the expense of fiction and lower expectations in math compared with Massachusetts’ current math frameworks.

In Kentucky, Commissioner Terry Holliday is considering many testing options, although Kentucky remains a member of PARCC and might be able to save money using the group’s tests. The state is already giving tests designed for the common standards, as well as ACT’s suite of tests in middle and high school.

Mr. Holliday said his state could stick with that arrangement, but it plans to issue a request-for-proposals in the fall to see what other vendors might offer for grades 3-8 and high school. He would consider proposals that emerge from that process, along with ACT’s new Aspire system, which is aiming for a $20 per-student price, as well as using Smarter Balanced or PARCC’s tests. He is also considering expanding the state’s own test-item banks with items from the two consortia’s item banks, he said.

“We’re going to treat PARCC and Smarter Balanced like any other vendor,” Mr. Holliday said.