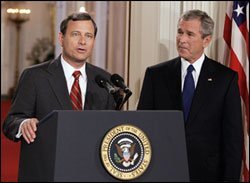

John G. Roberts Jr., President Bush’s pick to replace Justice Sandra Day O’Connor on the U.S. Supreme Court, has dealt closely with some of the most controversial issues in education as an appellate advocate.

If confirmed, he would bring to the high court perhaps the greatest firsthand knowledge of the concerns of district-level educators of anyone since Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr., who had served on both the Richmond, Va., school board and the Virginia state board of education before his service on the Supreme Court from 1971 to 1987.

“Among the names that were floated, I think he was the best candidate for schools,” Julie Underwood, the general counsel of the National School Boards Association, said of Judge Roberts. She noted that before he became a federal appeals court judge in Washington in 2003, he had several times spoken or participated at NSBA school law events.

“I believe he is so thoughtful and even-handed,” Ms. Underwood added. “Liberals are slamming him for briefs he wrote representing a conservative [presidential] administration. But I don’t think those briefs necessarily represent his personal views.”

Ms. Underwood was referring to Supreme Court briefs Mr. Roberts helped write when he was the principal deputy U.S. solicitor general during the administration of President George H.W. Bush. The briefs took conservative positions on such education issues as graduation prayers, school desegregation, and the scope of Title IX, the federal law that prohibits sex discrimination in federally financed educational programs.

Whether those briefs from 1989 to 1992 truly represent Mr. Roberts’ views is already being debated, given that an abortion-related case from that era resulted in a brief that he signed that called for a reversal of the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision establishing a constitutional right to abortion. Judge Roberts said in his confirmation hearings for his current post on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit that in signing on to such a position, he was acting as a lawyer for his client, in that case the administration of the first President Bush.

As deputy solicitor general in President George H. W. Bush’s administration, John G. Roberts Jr. co-authored briefs in these topical cases:

• Lee v. Weisman, a First Amendment case involving graduation prayer.

• Board of Education of Westside School District v. Mergens, an Equal Access Act case involving bible clubs in schools.

• Freeman v. Pitts, a case on school desegregation.

• Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell, a case on school desegregation.

• Franklin v. Gwinnett County Public Schools, a case invloving the mandates of Title IX.

Case information provided by the Legal Information Institute at Cornell University Law School.

In the brief in the school prayer case, Lee v. Weisman, Mr. Roberts and his boss, then-Solicitor General Kenneth W. Starr, called for the Supreme Court to replace its longtime test for evaluating whether government action violates the First Amendment’s prohibition against a government establishment of religion. The case concerned a rabbi’s prayer before a graduation ceremony at a public middle school in Providence, R.I.

“The graduation setting at issue here differs markedly from the classroom setting,” the brief said in calling for the court to uphold the practice.

In a major defeat for conservatives, the Supreme Court struck down the graduation prayers in a 5-4 ruling in 1992.

Mr. Roberts also helped write the administration’s briefs for two major desegregation cases, Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell and Freeman v. Pitts, which both addressed the issue of ending court supervision of desegregation plans. The first Bush administration argued for allowing school districts to ease their way out of such orders in stages, a view generally adopted by the high court.

In the Title IX case, Mr. Roberts’ brief took a narrow view of the sex-discrimination statute, arguing that it did not authorize awards of monetary damages. The Supreme Court concluded that it did, in a unanimous decision in Franklin v. Gwinnett County School District.

In response to President Bush’s nomination, liberal groups immediately expressed concerns, saying Mr. Roberts’ record in certain areas was, as People for the American Way put it, “disturbing.” The group criticized his brief in the graduation prayer case as “radical” and going “far beyond the case at hand.”

The Alliance for Justice, a Washington coalition that was instrumental in defeating the nomination of Robert H. Bork in 1987, said it was eager to find out more about Mr. Roberts’ views, but it could not support his elevation to the Supreme Court “at this time.”

‘Tough Questions’

After his service in the solicitor general’s office, Mr. Roberts returned to the Washington law firm Hogan & Hartson, where he argued a wide range of cases in the Supreme Court and sometimes helped the firm’s well-established education law practice.

In 1999, he argued before the high court on behalf of the National Collegiate Athletic Association in a case involving the question of whether the organization was itself subject to Title IX. The Supreme Court ruled unanimously in NCAA v. Smith that the sports body was not subject to the law merely based on the idea that it received dues from federally funded colleges.

Patricia A. Brannan, a former head of Hogan & Hartson’s education law practice, said she would often seek Mr. Roberts’ advice on appellate matters.

“I more than once came to John with the record in a case and said, ‘What do you think?’ ” she said. “He’s just superb at cutting through a heavy volume of material to the core issues.”

While at the firm, Mr. Roberts helped school district lawyers prepare for Supreme Court arguments by serving as a “judge” on the moot courts where they rehearsed their arguments.

Lee Boothby, a Washington lawyer who argued a case before the high court in 1999 involving federal aid to parochial schools in Louisiana, recalled how helpful Mr. Roberts was, even though Mr. Boothby ended up losing the case. Mr. Boothby represented local taxpayers who challenged such use of federal aid as unconstitutional.

“He asked some very tough questions,” Mr. Boothby said. “I felt very ill at ease about my case at the time I went into the moot court, but I felt much better prepared before the actual Supreme Court argument.”

In 2000, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in Mitchell v. Helms to uphold the provision of aid such as library books and computers to religious schools.

Mr. Roberts joined the federal appeals court in the nation’s capital two years ago. That court deals with much litigation related to the federal government, and probably fewer routine school district lawsuits than the other federal circuits. Judge Roberts has had no occasion for a substantive opinion on a school law issue there, but a widely discussed opinion of his in what is known in Washington as the “french fry case” may be of interest to educators.

The case involved not school authorities but Washington’s metropolitan transit authority, which in 2000 had staked out a subway station near a school, in part in response to complaints about rowdy students. The subway system has strict rules against consuming food or drink on trains or in stations, so when a 12-year-old student ate a french fry in a station, she was handcuffed and taken into custody.

The girl’s mother filed a lawsuit against the transit authority, alleging that the girl’s civil rights had been violated, in part because she was treated more harshly as a juvenile than adults customarily were for the same offense.

In an opinion for a three-judge panel that unanimously ruled for the transit authority, Judge Roberts said that “no one is very happy about” the circumstances of the case, but that “the correction of straying youth is an undisputed state interest and one different from enforcing the law against adults.”