An act of mass violence hasn’t yet touched the Benjamin Logan Local School District.

Superintendent John Scheu is thankful for that.

But for years, every time news broke about yet another school shooting, Scheu faced a handful of “what if?” questions.

What if a school in this small, rural district about an hour northwest of Columbus, Ohio—where the closest police outpost is 10 miles away—were the next target of a shooting? What if Benjamin Logan students were the next to have to huddle in closets sending “I love you” texts to friends and family? What if Scheu’s community were the next to have to mourn the loss of beloved students and staff members?

“If it can happen in all of these other places, it could happen here,” he said.

So, Scheu and his district invested hundreds of thousands of dollars in security. They hired school resource officers who are stationed at each of the district’s three schools. Security cameras send live feeds to the local sheriff’s office. Staff are reminded often that exterior doors are not to be propped open or left unlocked for any reason.

There’s a new mental health clinic at one of the schools, staffed with counselors trained to help the district’s roughly 1,600 students and 225 staff members.

District leaders felt confident they’d done all they could to keep outside threats from entering their buildings.

But what if the threat came from someone already inside?

Students and teachers have lockdown drills, and, as has become commonplace in American schools, they know to pull down the shades and lock the classroom doors before hiding quietly from a threat. But, beyond that, there isn’t much they would be able to do but “wait and hope that help would come,” Scheu said.

Except, Scheu asked himself, what if there were staff members trained to intervene? What if a handful of teachers, aides, and others could quickly reach for a firearm if an active shooter were targeting students?

“When you’re talking about putting out an active shooter threat, it’s a matter of seconds, not a matter of minutes,” said Scheu, who has served as superintendent in the district since July 2020. “And it’s a matter of life and death.”

After a year of planning, the district’s first “Armed Response Team” was in place to start the 2023-24 school year, part of a growing trend in Ohio and elsewhere in which schools tap teachers and other employees to act as the first line of armed defense against an active shooter.

An evolution of thinking on arming teachers

Scheu isn’t the first to have the idea of allowing trained educators to be armed, but he brings unique experience to the process of standing up a team of teachers with access to firearms on campus.

In fact, Benjamin Logan is the second district to develop a program under Scheu’s oversight in which teachers and other school staff take firearms training and have weapons at the ready.

He ushered in a related program at a nearby district nearly a decade ago, in Ohio’s Sidney City Schools, when he served as superintendent there.

In 2013—just a few months after 26 people were killed at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut—the district approved an armed response team, which remains in place today. Staff members in the program keep their firearms and bulletproof vests in specialized safes in the buildings that only open with the team members’ fingerprints, Scheu said. Nobody, however, carries a concealed firearm with them on campus.

Sidney City Schools’ current superintendent did not respond to EdWeek interview requests over the summer.

There are no national data on just how many schools have armed staff, but the controversial change has gained steam in the past decade, corresponding with a rise in American school shootings and widespread attention to the issue of gun violence on campuses.

Thirty-three states now allow teachers to carry guns at school, if approved by their local district. Those state laws have all passed in the past decade, after South Dakota became the first state to enact legislation allowing educators to be armed in March 2013.

Is 24 hours enough training?

The 17 staff members who started the school year on Sept. 5 as part of Benjamin Logan’s inaugural Armed Response Team spent the summer preparing. The group is a mix of 10 men and seven women, a combination of teachers and other school employees.

After undergoing background checks and mental health screenings, they participated in a three-day, 24-hour training at the end of June, which included classroom-based lessons and practice handling and using firearms at a local shooting range.

The lessons addressed when and when not to engage with a shooter, first aid, firearms handling, and self-defense, and included simulated drills of active shooter situations and target practice.

Under the Ohio state law allowing districts to have armed staff members, the participants required approval from the local sheriff’s office, the firing range instructor, coursework instructors, and Scheu.

Armed Response Team members will also have to complete eight hours of additional training each year, and the experts who conduct the training will have to reapprove the participants.

Some have raised concerns that armed educators in Ohio aren’t receiving enough training, especially in the past year, after changes to state law in June 2022 dropped the minimum number of required hours of training to 24 from more than 700.

Ohio’s main teachers’ union and its primary police union both opposed the change. In a year of debate, legislators heard testimony from those opposed to the change more than 360 times, compared with 20 times from those in support, according to NPR.

Jim Irvine, president of the pro-gun Buckeye Firearms Foundation, recently told a local news outlet that he doesn’t think the teachers across the state who have been certified to carry guns on campus in the past year, since the reduction in required training hours took effect, have been adequately trained.

“There are some things that are a mess with trainers that have been approved by the state that really don’t have the experience and the knowledge, we don’t think, to be doing this,” Irvine told TV station WSYX.

Scott DiMauro, the president of the Ohio Education Association—the state teachers’ union that represents educators across the state—agreed that the teachers involved are not receiving sufficient training. Twenty-four hours is not enough, he said, pointing out that other states, like Florida, require more than 100 hours.

“If we’re going to go this route, they should at least set a higher standard,” DiMauro said.

Scheu said he understands people’s concerns about the amount of required training, but said most Benjamin Logan employees on the Armed Response Team have participated in additional, voluntary training, and are committed to safety—that’s why they’re part of the program in the first place.

“They understand their commitment to being prepared and comfortable in their roles, and are invested in continuing their training,” said Scheu, who is not a member of the National Rifle Association and had limited experience with firearms before working with local police in Ohio to create the armed response teams. “We feel they are as well-trained as possible.”

All 17 Benjamin Logan staffers who participated in the state-mandated training received their required approvals, and none dropped out after the training, Scheu said.

That’s not always the case.

A few years ago, Scheu’s own daughter, a teacher elsewhere in Ohio, went through the training and passed before ultimately deciding she wasn’t the right fit.

“She told me she was glad she went through the training but just couldn’t do it, and I told her, ‘That’s fine. If you can’t do it, don’t do it. That’s why we have this process,’” Scheu said.

Participating school staff generally have firearms experience

Each Benjamin Logan staffer who is part of the Armed Response Team received a district-supplied handgun and has a biometric safe for storing the weapon that only opens with their fingerprint, rather than a passcode, in their classroom or office. Some are allowed to carry their firearm with them on campus concealed, while others store their guns in the safes at all times. That depends on their preference, the grade they teach, and the recommendation of the school resource officers and local sheriff.

One middle school teacher in the program said he felt compelled to participate because he has a long history of handling and training with firearms—a background he said most other participants shared.

“My kids go to school there. My friends’ kids go to school there. There are people I’ve worked with for almost 20 years, and they become your friends as well,” the teacher said. “So it’s kind of just protecting family and friends and students. That’s something I want to be able to add to what I do here.”

Education Week is not naming the teacher because district policy and state law require that participants’ identities not be disclosed to protect their own safety and the program’s integrity.

Much of the pushback against arming educators in the district has come from people who don’t have much personal experience with firearms, the teacher said.

“It’s something they’ve never experienced, or only experienced through a negative lens,” the teacher said. “My personal feeling about it is if they took the time to learn more about it and what we’re trying to do, they may feel differently about it.”

A life-saving strategy or dangerous gamble?

Although the majority of states allow teachers to be armed at school, the idea remains controversial.

Advocates say having staff on site who can respond in emergencies can cut the amount of time those in the school have to spend waiting for first responders—time that can save lives. Proponents also say that just the knowledge that there are staff on site who can and will intervene with weapons can deter potential acts of violence altogether.

However, opponents argue having firearms on campus is a dangerous gamble.

On top of piling another non-teaching responsibility on teachers, guns could accidentally discharge, get stolen by students or other staff, or create even greater confusion when there’s an active shooter.

National groups including the National Education Association, the National Association of School Psychologists, and the National Association of School Resource Officers have opposed arming teachers and school staff.

Support in the Benjamin Logan district hasn’t been universal, either.

At a public forum last summer, Scheu said a handful of people, many of them teachers, voiced concerns about colleagues carrying or storing firearms.

The local teachers’ union pushed back, too, he said.

The initial school board motion in the spring of 2023 to create the Armed Response Team passed by one vote, 3-2.

The initiative, however, garnered unanimous support in another school board vote in late August, following the conclusion of the Armed Response Team’s training. The two board members who initially opposed the team’s creation didn’t respond to requests for comment.

When you’re talking about putting out an active shooter threat, it’s a matter of seconds, not a matter of minutes. And it’s a matter of life and death.

The Ohio Education Association is firmly against arming teachers, said DiMauro, the association’s president.

Having more guns on campus often makes other teachers uncomfortable and can distract them from doing their jobs, he said. But arming teachers is also a “shortcut approach” that puts more responsibility on teachers and less pressure on state officials to provide funding for “better trained” and “more appropriate” staff to manage school safety, like security guards and SROs, DiMauro said.

“I do think it’s a way for the state to shirk its responsibility … to provide funding so that you can have fully trained people who specialize in that work in our schools,” he said. “I understand the arguments, I do. But taking a step back and looking at the big picture, I don’t think this is the best way to address this need.”

Districts would be better served if state and federal lawmakers made a stronger effort to address the “root problems” of school violence, DiMauro said, like cracking down on who is able to access firearms in the first place.

‘We really don’t know anything’ about the effectiveness

Teachers generally appear to have major doubts that allowing educators to carry firearms on campus will make schools safer.

Fifty-four percent of educators polled late last year by the RAND Corporation said having armed teachers would make campuses less safe, as opposed to 20 percent who said doing so would make schools safer. Educators in rural districts were more likely to support arming teachers, with about a third saying the initiative would make schools more safe.

There are signs, however, that support among educators is growing.

Heather Schwartz, a researcher at RAND, said older surveys of educators’ opinions on arming teachers had shown less support for the initiative, which suggests there is “a national evolution in attitudes about it, and a more accepting attitude in many places.”

There are little data, though, about the “early adopters” that have employed armed teachers, Schwartz said, so there are many questions about the policy’s effectiveness, including its impacts on school climate and how closely armed staff are complying with training requirements.

“We really don’t know anything—not even just the basics of implementation,” Schwartz said.

A response to a problem, not a political statement

In the Sidney City and Benjamin Logan districts, the programs were designed as a response to a problem, not a political stand, Scheu said.

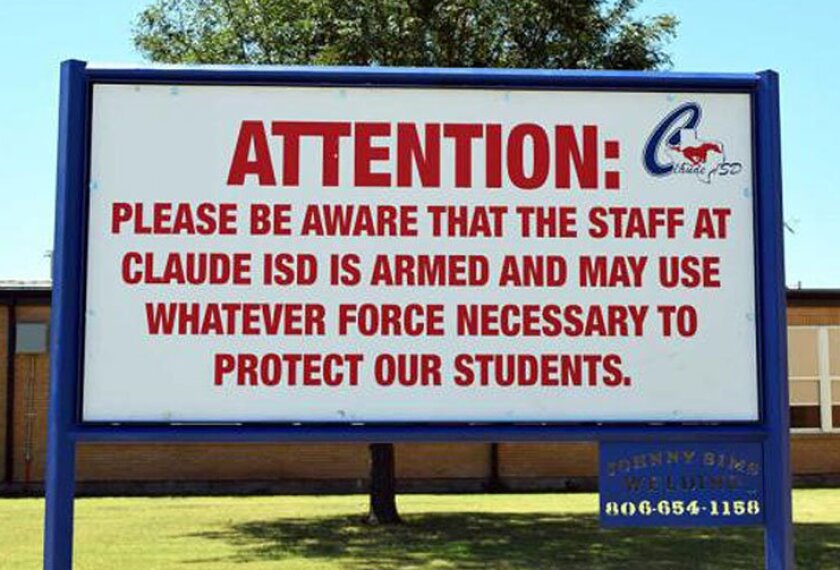

And the superintendent believes it’s a proactive step that could prevent a would-be shooter from targeting his community. Signs posted by the entrances to each of the district’s three schools warn would-be shooters that there are armed staff on the premises.

“In my opinion, just having the Armed Response Team serves as a definite deterrent because these active shooters will always seek out soft targets,” he said. “By putting up signs telling people, it’s not that we’re bragging. It’s just a matter of telling people that we’re not a soft target—do not pick us to do your carnage.”

Even now, when Scheu feels confident his district is doing everything it can to protect students and staff, a “what if?” still lingers in his mind.

What if something goes wrong with the Armed Response Team and someone is accidentally killed or injured, or a gun ends up in the wrong hands—all reasons others have cited in opposition to arming teachers?

“That is a concern any time you have an armed presence in the building, if something could go astray,” Scheu said. “But the flip side of that is, if you don’t have any plan and the shooter comes in and just kills innocent kids who are hiding under tables with no way of putting out that threat, how much sense does that make?”