Historic heat waves across the United States thwarted the start of the 2022-23 school year, forcing schools to shut down, pivot to remote learning, or dismiss students early in the day.

2022 marked the nation’s third-hottest summer on record, with several states seeing record-breaking temperatures stretch into September. Schools across the country—in Philadelphia, Baltimore, Cleveland, Denver, and San Diego, among others—closed due to excessive heat. In Columbus, Ohio, teachers went on strike demanding air conditioning in classrooms.

Experts say all of that is a foreboding harbinger of what’s to come.

As climate change accelerates, temperatures will continue to rise well into the school year, including in regions that aren’t used to hot weather. Many schools don’t have air conditioning units that are equipped to cope with sweltering heat. And a body of research shows that hot classrooms are detrimental to student learning.

“Schools are not prepared for the extreme heat, and we need to change that now,” said Jonathan Klein, the co-founder of UndauntedK-12, a national nonprofit supporting climate action in public schools that tracks school closures due to heat and other extreme weather.

It’s also an equity issue, he said: “Our most vulnerable students are the most vulnerable to extreme heat.”

How does heat affect student learning and well-being? How well are schools prepared for the longer, hotter summers to come? Here’s what you need to know.

Does heat affect student learning?

Yes, heat makes it harder for students to learn. Students perform worse on tests when they’re hot, according to multiple studies by economists R. Jisung Park and Joshua Goodman, among others.

One study tracked 10 million secondary students who took the PSAT, a standardized exam used to identify students for college scholarships, multiple years between 2001 and 2014. The researchers found that cumulative heat exposure decreases the productivity of instructional time—without school air conditioning, a 1 degree hotter school year reduced that year’s learning by 1 percent.

The effect was three times more damaging for Black and Hispanic students than for white students, that study found. A similar discrepancy was found for students from low-income households compared to their affluent peers.

Students from low-income households are 6.2 percentage points more likely than their more affluent counterparts to be in schools with inadequate air conditioning, the study found, and Black and Hispanic students are 1.6 percentage points more likely than white students to learn without air conditioning. Schools that serve predominately students from marginalized backgrounds often have fewer resources to invest in infrastructure.

Another study analyzed data from 4.5 million New York City high school exit exams to find that students scored significantly lower on the standardized state test on a 90 degree day than on a 72 degree day. And importantly, it found the consequences were lasting: The study linked exam-time heat exposure with a lower likelihood of on-time high school graduation.

A separate recent study that examined data on state exams for 3rd to 8th graders found that the impact of heat on mathematics achievement is about three times larger than its impact on achievement in English/language arts.

Educators say students can be unmotivated and distracted when sitting in a hot classroom. And other research shows that cognitive function declines during excessive heat, leading to slower reaction times on assessments.

Finally, students who don’t have air conditioning at home are at more of a disadvantage because heat also affects sleep, said Dr. Aaron Bernstein, the interim director of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at the Harvard School of Public Health. And sleep, of course, affects performance the next day.

“If you don’t sleep well because it’s too hot, you don’t think well,” he said.

Does heat affect students’ social and emotional well-being?

It can. The saying, “I can’t think straight, it’s too hot,” is backed by science: Heat can make people more impulsive and less able to regulate their behavior, Dr. Bernstein said. Decisionmaking skills deteriorate with heat. As a result, students might act out more during hot days.

And there’s a body of research showing that people are more aggressive and violent when it’s hot outside. Experts say this could extend to higher rates of bullying among students.

Does heat affect students’ physical health?

Public health experts warn that children are more susceptible to heat illnesses than adults. Heat-related illnesses can include muscle cramps, heat exhaustion—which may come with nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and fever—and heat stroke, which in extreme cases can lead to seizures or even death.

Student-athletes are particularly at risk for heat-related illnesses, as they often practice and compete outside. Football players are by far the most at risk for heat-related illness—at least 50 high school players in the nation have died from heat stroke in the past 25 years—followed by female cross-country athletes.

Experts say many states—especially those that haven’t previously experienced dramatic heat waves—need to strengthen their heat-safety protocols for student-athletes. Those include adherence to a defined heat-acclimatization process that gradually increases the length of training sessions and the intensity of workouts, as well as coaches or athletic trainers who are trained in monitoring heat safety.

School bus rides can also be a cause for concern. Students often ride a bus without air conditioning for extended periods of time, and schools across the country have reported instances of children overheating on school buses and experiencing symptoms of heat-related illness.

Students who have medical conditions should also be monitored on hot days, Dr. Bernstein said: “Heat can make any chronic medical problem worse.”

How frequent are hot school days?

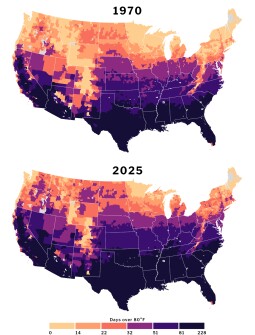

School days over 80 degrees Fahrenheit are becoming more frequent, research shows. A report published last year by the Center for Climate Integrity, a left-leaning environmentalist advocacy organization, estimates that between 1970 and 2025, there will be a 39 percent increase in the number of school districts that see 32 or more days over 80 degrees Fahrenheit. (Eighty degrees outside can lead to high temperatures indoors when there’s no air conditioning.)

Another finding: 1,815 school districts—serving about 10.8 million students—will see three more weeks of school days over 80 degrees in 2025 than they did in 1970.

Most hot school days occur in August and September, but some regions will also start to see hotter-than-normal temperatures in May and early June. Due to climate change, summers are expanding while spring, fall, and winter are becoming shorter—and warmer.

What is the ideal temperature for the classroom?

The ideal temperature range for effective learning in reading and mathematics is between 68 and 74 degrees Fahrenheit, according to a research report by Pennsylvania State University’s Center for Evaluation and Education Policy Analysis.

Experts agree that classrooms would ideally be kept at a temperature that doesn’t require fans, space heaters, or winter wear to make students and staff more comfortable.

One study, conducted in 2004 and 2005 on two classes of 10- to 12-year-old children, found that student performance on two numerical and two language-based tests improved significantly when the classroom temperature was reduced from 77 to 68 degrees Fahrenheit.

How many schools don’t have adequate air-conditioning units?

While national data are scarce, estimates suggest that anywhere between one third and one half of U.S. classrooms don’t have adequate—or any—air conditioning. A nationally representative EdWeek Research Center survey, conducted in summer 2021, found that nearly half of educators said heating and cooling problems were an urgent issue in their school districts’ facilities.

Two-thirds of district leaders said more than three-quarters of their school buildings have air conditioning in classrooms, but there were disparities by region. Only 20 percent of educators in the north said all their buildings have air conditioning, compared to 88 percent of respondents in the south.

A few decades ago, schools in many parts of the country didn’t need air conditioning because the climate was more temperate, said Paul Chinowsky, a professor emeritus of civil, environmental, and architectural engineering at the University of Colorado Boulder.

In the past, you could draw a line across the United States—from Washington, D.C., all the way to Southern California—and expect that everywhere south of that line would have appropriate cooling systems in their schools. But with the changing climate, that line has moved up. Now it passes from Philadelphia through Cleveland and Chicago, Chinowsky said—and yet many schools in those regions don’t have air conditioning.

Even schools that do have air conditioning may have aging systems that are not equipped to keep up with the changing temperatures. Chinowsky said many cooling systems were once designed to run six to eight hours a day for only a short period of time, and now they need to run for up to 18 hours a day for many weeks to keep up with longer, hotter summers.

“We see a real reckoning coming for the entire education system,” Chinowsky said. “The physical facilities in it were built for an environment that was in the 1980s and before. … The reality of what conditions are today and what they’re going to be in 10 to 15 years is a completely different world from what they were 20 years ago.”

What do schools do instead when it’s hot out?

When schools don’t have air conditioning, they often make do by opening windows and purchasing box fans to cool down classrooms. That can help mitigate the worst effects of the heat, experts say, but it’s not a reliable solution for all.

If the temperature inside the classroom is close to 100 degrees, it’s too hot for a fan—the fan will have the same effect as a convection oven and make people feel warmer.

Some schools dismiss students early during extreme heat, and others cancel classes entirely. Chinowsky said his research suggests that school districts cancel school for heat an estimated average of six or seven days per year—up from three or four days a decade ago.

Now that most schools have the infrastructure set up to do remote learning, several districts have opted to have students learn from home on particularly hot days instead, to avoid a disruption in learning time. Experts say this could become a more common occurrence, even though pandemic-era studies have found that remote learning doesn’t work well academically for many students.

“Many schools are saying it’s less expensive to do remote learning on those hot days than [it is to] invest in cooling schools,” Chinowsky said. “But everyone knows that’s not an optimal solution, especially if you’re doing random remote learning days at the last minute.”

What else can schools do to prepare for increasingly hot school days?

Addressing the air conditioning crisis in schools will cost tens of billions of dollars.

Federal pandemic relief money can be used to improve ventilation in schools, including installing or upgrading air conditioning units. But experts say that money alone won’t fully solve the problem, and policymakers should continue to invest in schools’ aging infrastructure.

Schools can mitigate the heat through other infrastructure choices. For example, when it’s time to replace a school’s roof, white roofing can lower the building’s temperature by several degrees. If there’s an opportunity to revamp the playground, avoid black rubber, which gets very hot. Planting trees on school grounds can provide natural shade and cool the air around them.

“Resources are scarce, but when we do make decisions that deal with infrastructure in schools—roofs, windows, playgrounds, trees—any of these things can affect the temperature of the school,” Dr. Bernstein said.