Never mind that she’s 15, in 9th grade, and a bit out of place among the toddlers playing at their mothers’ knees in the waiting room of the state-run health clinic in this Washington suburb.

If Rachel Trail had to get a shot, she figured that like the other youngsters, she should get a treat.

“I’m one of those panicky-type people,” she said, laughing, one day this month. “When I get my shot, I want a sucker, and a sticker.”

And true to her request, Ms. Trail, a high school freshman, returned to the waiting room after receiving her shots with a Dora the Explorer sticker right over her heart. The shots were “just a pinch,” she said.

Ms. Trail was one of thousands of teenagers in Maryland who found themselves at the other end of a needle—or its state-of-the-art equivalent, a device that administers immunizations through the skin using a blast of compressed air—after state health officials decided in 2005 to accelerate the vaccination schedule for the state-mandated vaccines for hepatitis B and varicella, commonly known as chickenpox.

Maryland’s scramble to get middle school students up to date on their vaccinations serves as a cautionary tale for school and public-health officials nationwide.

Vaccines are one of the triumphs of modern medicine, relegating many once-fearsome diseases to the history books. And denying access to school has long been the best way to ensure that children get vaccinated. But carrying out any change in immunization policy means a lot of work for school officials.

“We’re the enforcement,” said Debbie Somerville, the coordinator of student services for the 107,000-student Baltimore County school system, which does not include the city of Baltimore. “It becomes the school’s burden to find out who’s the problem child.”

Several states, including Maryland, are considering changes to their immunization regimens to include the new vaccine against human papillomavirus, or HPV, as a requirement for public school attendance. No state has yet made the HPV vaccine mandatory, though it is recommended by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in Atlanta.

It is the law in all states that children be properly immunized before attending school. In addition to medical exemptions offered in each state, 28 states allow religious exemptions and 20 states allow personal-belief exemptions that include religious, philosophical, or other unspecified nonmedical reasons.

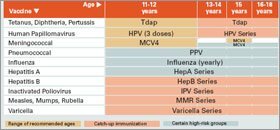

*Click image to see the full chart.

SOURCE: Institute for Vaccine Safety

The requirement for hepatitis B and varicella vaccination was added to Maryland’s immunization regimen in 2000, and had been phased in year by year, starting with kindergartners. Accelerating the implementation schedule forced officials in the state’s 24 school districts to comb through sometimes-incomplete records to find out which of their older students didn’t have the shots.

Some 55,000 students were found to be out of compliance. Those students then had to get appointments to take the shots, show proof they had already received them, or risk missing part of the second semester of school, which began Jan. 2.

As of mid-January, some districts reported that employees were still knocking on the doors of the last few students whose families had not responded to repeated efforts to contact them.

The challenges in putting immunization policies into effect become particularly noticeable when the vaccines are intended for adolescents. Parents are generally aware that babies and toddlers need shots to enroll in school; about 75 percent of recommended vaccines are administered before a child is 18 months old.

Parents tend to be less aware of the vaccines recommended for older children.

Most vaccines are administered before a child is 2 years old. However, medical experts recommend certain vaccines for adolescents. Not all are required by all states.

*Click image to see the full chart.

SOURCE: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

“He’s 14, so I figured he was done with all his shots,” said Marion Leonard, whose son Davon, a 9th grader, showed up at the clinic for a varicella vaccine.

In addition to HPV, adolescent vaccines recommended by the CDC, include one against meningitis and a combined booster shot against tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis. Adolescence is also considered a prime time to catch up on any other vaccines that were missed in early childhood.

Though the CDC makes recommendations, it is the states that make and enforce immunization policies for schools.

“As states look at immunization, they need to partner with education,” Ms. Somerville said. “This is an opportunity to look carefully at these requirements, and what happens when you change vaccination requirements mid-school-career.”

The important role that schools play in implementing vaccination policies became apparent in the mid- to late 1970s. In 1976, Alaska experienced a sustained measles epidemic, despite a vaccination requirement. Along with offering free clinics, the state health department and schools tightened up enforcement efforts by telling parents that they had to show proof or risk school exclusion. Within three months, the outbreak was halted. A similar measles outbreak in Los Angeles in 1977 was stopped when schools excluded children and made free clinics available.

“Even in the middle of measles outbreaks, some parents just made it a low priority,” said Dr. Walter A. Orenstein, the director of the program for vaccine policy and development at Emory University, in Atlanta, and a former director of the National Immunization Program, based at the CDC. It takes the schools’ involvement to focus parents, he said.

“Most of us are much more preoccupied with day-to-day problems than to try and prevent a disease some time in the future,” Dr. Orenstein said. “The laws are designed, in part, to make [immunization] a higher priority.”

More recently, an outbreak of pertussis at a large high school in a Chicago suburb illustrated how immunizations are often dependent on school action. Several cases of pertussis, also known as whooping cough, were documented at the 4,000-student New Trier Township High School campus in Winnetka, Ill., in December. Whooping cough is not a fatal disease in older children and adults, but can be dangerous to the very young. It leaves sufferers with a wracking cough that can last for weeks.

More than 30 cases were reported among New Trier High sophomores, juniors, and seniors, all of whom had been given pertussis vaccines in childhood, but the effectiveness had worn off over time. The school started barring students from attendance if they had any coughing illness, but the county health department still wasn’t seeing a high rate of booster shots among students, despite recommendations.

Finally, the health department bought vaccine and administered the booster shots on campus Dec. 11, said Dr. Catherine Counard, the assistant medical director for communicable-disease control for the Cook County Department of Public Health.

Some parents said they were having problems getting the vaccine, she said. But others said that they just weren’t worried about it.

“We as a society are pretty complacent about infectious diseases because we don’t have experience with them,” Dr. Counard said. The outbreak now appears to be over, she said this month.

But while school involvement is essential, it is also time-consuming for personnel.

Ann Hoxie, the administrator for student wellness for the 40,000-student St. Paul, Minn., district, also serves on the immunization-practice advisory committee to the state health department. She recalls making a trip to Atlanta when the CDC was discussing whether the vaccine against hepatitis B, a viral liver disease spread through sexual contact or blood, should be a recommended vaccine for children.

“One person said, ‘We shouldn’t even be talking about this. Let’s pass a law and get it done.’ I stood up and said, ‘On whose resources?’ ” Ms. Hoxie said.

She said the argument is not about the value of vaccines.

“It’s just a huge balancing act, and we only have so much time,” she said. “It does take significant school resources.”

Ms. Somerville, of the Baltimore County school system, said work began at the end of the 2005-06 school year to prepare for her state’s change in immunization policy. The original intent was that the revised policy would be in place for the start of the 2006-07 school year, but schools received a one-semester extension.

“We spent weeks talking to parents,” Ms. Somerville said.

Rhonda C. Gill, the director of student services for Maryland’s 74,000-student Anne Arundel County district, reported the same level of interaction with parents. Right now, she said, the effort has shifted from health services to the school personnel who handle truancy. The families that the district hasn’t been able to get in touch with, she explained, probably have children with chronic attendance problems.

Ms. Gill’s take on the new immunization mandate is that there have always been problems in getting some children the vaccinations they need, she said.

But “it hasn’t gotten the level of publicity this has received, because it’s been routine,” she said. “Once we get past this, this too will become routine.”