Tim Schlosser taught English/language arts for five years before becoming a principal.

With that experience and expertise, Schlosser, a principal of Tyee High School in SeaTac, Wash., can show ELA teachers what it’s like to break down an academic content standard, and how to plan an effective lesson.

“I am able to relate to literacy development challenges, the challenges with finding high-interest, but on-grade-level books for students to read,” Schlosser said. “I am able to connect, relate, offer guidance, or empathy, even. All of those things do add a dimension to coaching and to the conversation that it’s hard to claim doesn’t have a value-add.”

But what sort of “value-add” can Schlosser bring to a calculus teacher or Spanish teacher?

“A principal’s role is not to be the instructional coach and content-expertise developer for all people,” he said. “The principal’s role is to ensure that all people are getting content-expertise development and support.”

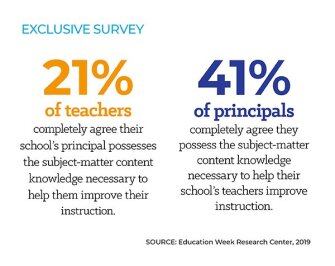

How deeply principals should know the subjects taught in their school and how much that matters are still an ongoing debate in leadership circles.

The oft-repeated mantra has been “good teaching is good teaching” and that principals should be steeped in effective teaching practices, which invariably transcend content and grade level.

But over the last decade or so, there has been a burgeoning argument around whether taking a deeper dive into subject areas outside their expertise would put principals in a better position to coach and support all teachers.

Grounded in Good Teaching

There’s broad consensus that principals need deep knowledge in three broad areas: curriculum and pedagogy; assessments for student learning; and classroom environment and culture.

With a firm grounding in those areas and equipped with guided questions, principals can have educated conversations with teachers about strengths and weaknesses across grade levels and subject areas, and connect them with experts who can help if principals do not know the subject deeply, said Ann O’Doherty, a former principal and director of the Danforth Educational Leadership Program at the University of Washington.

“These are general, broader areas that a principal needs to know and be able to recognize—when they are seeing those practices and not seeing those practices, and have a sense of how to move teachers along,” O’Doherty said. “I think having a deeper understanding of that teaching and learning framework is essential, and that people start with that.”

Principals should understand academic standards for every grade level in their school and have a working knowledge of the curriculum and teaching materials, said Susan Korach, an associate professor of education leadership at Morgridge College of Education at the University of Denver. But also essential is knowing how to evaluate and collect evidence that students are learning, she said.

At the same time, Korach said, principals are responsible for making sure there’s content-level expertise in the building, even though it may not be theirs.

“The recognition that ‘I don’t know enough about something’ should propel the leader to work with people who are experts on what kinds of support would help fill in the gaps,” Korach said.

But other academics are suggesting that when principals possess content knowledge beyond the subject they taught, they can be even more effective at improving teachers’ instruction.

While it is unrealistic and unfair to expect a principal to know deeply the content of all that’s taught in their school—including subjects many may not have taken when they were students—principals shouldn’t just lean on the refrain that “good teaching is good teaching” and point teachers in the direction of experts when the need arises, said Jo Beth Jimerson, an associate professor of educational leadership at Texas Christian University.

Jimerson and Sarah Quebec Fuentes, an associate professor of mathematics education at TCU, have been conducting interviews with 31 educators—15 administrators and 16 teachers—to understand how much principals’ content knowledge matters.

They found that principals who do not know the content often relied on the good teaching refrain and provide feedback that generally dealt with “atmospherics"—classroom climate, student interactions.

“There is definitely value to the kind of ‘good teaching is good teaching’ mantra, where there are certain crossover practices that appear to be beneficial no matter what the content is,” Jimerson said. “So how we are engaging students, how we are using formative assessments, these kinds of things do seem to be both content neutral and valuable.”

But teachers have also told them that the feedback from principals who had “even a modicum of baseline knowledge of how the content is taught” was more actionable and valued, Jimerson said.

An algebra teacher, for example, told them it was more valuable to have a principal who could discuss functions, “than it was for somebody to ask ... ‘whether I had done a thumbs-up every seven minutes,’ ” Jimerson said.

“So, teachers value the crossover practices, but when administrators have some kind of content knowledge, they seem to be able to see what they are observing in the classroom in a much more complex and nuanced way,” she said. “It does add value to that feedback, and it also seems to improve the relationship and credibility between the teacher and the leader.”

But to muddy the waters a bit, the inverse was not necessarily true. A principal’s lack of content knowledge did not negatively impact the relationship between the teacher and the principal. Teachers, for the most part, already knew what their principals taught, and principals who admitted to some weaknesses and were interested in learning alongside teachers added to the principal’s credibility.

From her research, Jimerson believes that while there are common teaching practices that help, principals who can gain a baseline understanding of how to teach content outside their area of expertise can be more effective at helping their teachers and finding the right professional-learning resources and mentors.

That skill can be particularly useful in cash-strapped districts, where every school may not have an instructional coach or subject-matter expert, or in rural school districts where the principal has to wear many hats.

So, just how can principals expand and build their expertise? Jimerson suggests these steps:

• Choose one subject area a year and dig deeper into it.

• Subscribe to a practitioner journal in one content area, such as the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics’ journal. Principals should read it monthly, and discuss it with their teachers.

• Make the learning public. Teachers and other experts in the building and districts should know that principals are engaging in this process.

• Have conversations with teachers about what you’re reading and ask to visit classrooms to see in practice what you’ve just read.

• Work with the district’s instructional coaches and content experts in the area of focus. Visit classrooms with them to see and learn good teaching practices in that subject area.

• Read one or two well-respected practitioner books in that content area.

• Attend professional learning community meetings in that subject area, not as a leader, but as a co-learner.

Those steps will give the principal a more nuanced look at teaching in an area outside of his or her expertise. And as part of sharing instructional leadership with other senior team members, the principal can ask the assistant principal to do the same to deepen their expertise. If they choose a different subject each year, over the course of time, they would know much more about the subjects that are being taught in their schools than they did when they started, she said.

“Nobody can know everything, we clearly agree with that,” Jimerson said. “We do think that it’s within the leader’s ability to know something about different areas, and that’s the important point that we’ve been more focused on. It’s that, ‘How can you know more over time? How can you have an intentional learning plan to build your content knowledge so that you can better engage around instruction with teachers?’ ”

Avoiding Blind Spots

But there is some inherent value in principals knowing that they are not the experts. If principals assume they are not the experts in a particular field, it can eliminate the possibility that they develop blind spots, particularly in those who may not have taught in a specific content area for some time, Korach and Schlosser said. It also keeps them in a continuous learning mode.

They can also draw from their lack of expertise to help teachers, by asking probing questions from a learner’s perspective that can force the teacher to think more deeply about lesson planning or teaching strategy.

“You can position yourself as a learner because you authentically are the learner,” Schlosser, the principal, said. “You don’t understand the content, and so you’re right there alongside the student experiencing the struggle with them, and in that sense could be offering more valuable feedback ...”

In the cases where gaps in content knowledge may be an issue—particularly between a new principal and the school’s veteran teachers—the leader has to be transparent about what he or she does not know and reinforce that the teachers’ expertise is respected and valued, Korach said. Principals must build a culture that’s based on collaboration and teamwork, she said.

It’s exactly that kind of collaborative learning environment—grounded in teacher expertise—that Jack Baldermann, the principal of Westmont High School in Westmont, Ill., and the 2017 Illinois Principal of the Year, sought to create in the school.

Baldermann, now in his eighth year as principal at Westmont, credits the school’s content-based professional-learning communities where teachers and coaches share expertise on everything—from common writing rubrics, formative assessments, collaborative analyses of student performance—for the school’s academic improvement.

Baldermann knows good teaching practices, but teachers have told him that the collaborative learning experiences with their peers who know the content deeply are more beneficial.

“I am not offended if they say they think this is helping us more with our growth than a traditional formal evaluation by an administrator,” he said. “I just think it makes sense.”

Westmont’s five-member math data team, which meets once a week to review student data or to help each other with teaching strategies, has been polishing its professional learning community approach over the last four years, digging deep into data to unearth gaps in student learning and plan interventions. One thing the group does is take the general teaching strategies suggested by the principal and devise ways to fit them into the content.

The administrator may notice that a student is not engaged in a group activity, and make a suggestion that the teacher think about including one in the lesson, for example, said Marc DeLisle, a math coach and teacher at Westmont. The math teacher would take the suggestion to the professional learning community and the members would deliberate over the best response.

“What would be a group activity for graphing quadratics?” DeLisle said. “Then we would brainstorm on that ... Would a think-pair-share be good? Would jigsawing be good? That kind of stuff.”

“A lot of it is informal conversation,” DeLisle said. “Somebody would come in and say, ‘I am struggling with factoring. How do you teach it?’ Some teachers may use the box method, some teachers may use guess and check. Somebody may have a great activity to do it. So that’s just part of being the team—bring where you are struggling, and we’ll use our strengths to help other people.”

Westmont math teacher Katrina Zorbas agrees they don’t turn to administrators for content expertise, but value the general teaching strategies they get from the principal.

“We have each other in the department for content-related development, I don’t think that’s what I would be looking for [from the principal], to be honest,” she said.

For Principal Schlosser, the most important thing is setting up teachers for success. Sometimes he has the expertise they most need. Other times, the assistance comes from someone else.

“I think, ultimately, without necessarily including myself, when you get to really high-performing principals, they are respected for reasons that don’t have anything to do with their content knowledge or expertise,” Schlosser said.

“They are respected exactly for the fact that their ability to support people goes far beyond their own specific content background or expertise. “