As Jo-Ann G. Ordoyne takes the roll in her 11th grade American history class, about half the names she calls out are greeted with silence.

“Fernando?” says Ordoyne, a teacher here at Bonnabel High School for 33 years. “Anybody hear from Fernando?”

No one answers.

“Megan?” she calls out a few minutes later.

“I heard that she’s not coming back,” one student replies.

It is Monday morning, Oct. 3, the first day back for public schools in Jefferson Parish—just outside New Orleans—since Hurricane Katrina struck southeastern Louisiana on Aug. 29. Since that day, Ordoyne’s students have been scattered far and wide: Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, Panama City, Fla., Shreveport, La., and St. Louis.

Now 15 of them are reunited, but things are definitely not the same. They’ve all been through a lot, and so has their school.

First, there was the storm. Roofing was ripped off some of the beige, block-like buildings that make up Bonnabel High’s nondescript campus nestled in a suburban neighborhood near the New Orleans airport. Heavy rains flooded halls and classrooms. Powerful winds leveled trees. Parts of the campus were under more than a foot of water.

And then there was the mess left after the school was pressed into service as an evacuation center. Filthy clothes, rotting food, urine, and feces had soiled hallways and classrooms.

Still, five weeks after Katrina landed in Louisiana, Bonnabel and 78 other Jefferson Parish schools were welcoming students back—and far sooner than many had expected.

“It was an incredible effort by a whole lot of people,” says Diane Roussel, the superintendent of the district, which enrolled 49,000 students before the hurricane forced mass evacuations in the New Orleans area.

As school resumes, Ordoyne’s regular classroom is still off limits, with cleanup contractors removing ceiling tiles, flooring, and plasterboard. The teacher is in temporary quarters that are not nearly as fancy as her old space, dubbed the “Fourth of July” room by cleanup contractors because of its elaborate red, white, and blue decorations.

Read the related story,

Still, the 55-year-old educator has festooned the room with eye-catching extras: stuffed bears in honor of the school mascot, a big poster from the movie “Meet Joe Black,” and placards with slogans like “You never, never, ever give up!”

On the front chalkboard, she has written: “Welcome back, Bruins!”

In her makeshift surroundings this first morning back, Ms. O., as Ordoyne’s students call her, shares some of her own experiences and invites the students to speak up, too.

“We have all lost something,” she tells the class. “But in spite of all our personal misery, we are here, and we know the value of education.

“The future that you envision for yourself,” she adds, “begins again today.”

The ‘C’ List

The worst damage in Louisiana from Hurricane Katrina didn’t come to Jefferson Parish. That distinction was reserved for portions of New Orleans, as well as St. Bernard Parish, where large areas were deep under water. Public schools still are closed in those areas.

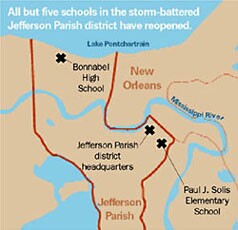

Even so, Jefferson Parish didn’t get off easy. The district headquarters remains unusable. Five of the system’s 84 public schools were damaged so badly that they still have not opened, and may well be written off altogether. Many local businesses remained closed the first week of October, including two major shopping malls.

Days after the storm hit, district leaders began the task of getting the school system open again. At an early-September school board meeting—held in Baton Rouge, the state capital—district officials estimated that about half the schools would be ready for the target reopening date of Oct. 3.

Schools were divided into three categories—A, B, and C—based on the extent of damage. C schools had the most severe damage, and were not expected to reopen on the target date, if ever.

Bonnabel High was on the C list. So was Paul J. Solis Elementary, due south of New Orleans, across the snaking Mississippi River.

Despite its C-list status, Ginny S. Dufrene, the principal of Solis Elementary, was determined to get her school ready in a hurry. Among the tasks was pushing standing water out of the main building.

“All of the trees were down in the backyard,” recalls Dufrene, 51, thumbing through a photo album of the damage during a tour of the school. “Sixty-five percent of the roof was gone. … One classroom had about four inches of water in it.”

She points to another photo: “This is a 14-foot glass window that was blown to the middle of the floor.” And, she recalls, “stink bugs” were all over the foyer.

Another picture shows National Guard troops from Oklahoma and northeastern Louisiana removing fallen trees.

“I didn’t have any food or drink or anything to give these people,” laments Dufrene, who is quick with a hug and has an easy familiarity with her students and teachers.

Scott B. Adams, the construction manager for the Jefferson Parish schools, praises Dufrene and some of her teachers for making “a Herculean effort. ... They were true heroes in this thing.”

Hauling Trees, Bleaching Walls

If there was a hero at Bonnabel High School, by some accounts it was Alan P. Forcha, the school’s plant manager, who stayed on campus throughout the storm and afterward. He did all he could to minimize the damage, and barely slept the week of the storm.

“I never, ever thought the school would open” on time, he says. “It was just trashed.”

The school was not supposed to be an evacuation center, he says, but at the last minute, the police said it was needed to take in displaced people.

“I had to turn it over to the authorities,” he recalls. “It was crazy; it was chaos.”

In all, some 2,000 evacuees stayed at the school over the course of seven days, he says, though they came and left in waves.

“Most of the people who came in had no food, no water, they had nothing,” Forcha says. The situation worsened when the buildings first lost power, and then water.

“The buildings were just deplorable,” says Raymond Ferrand, Bonnabel’s principal, in describing the damage inside from its use as a shelter. “That was probably the biggest shock to all of us.”

Ferrand says some items, including physical education uniforms and sweat suits, were taken; he estimates the school lost “$5,000 worth of stuff” that way.

Teachers and other staff members helped with some of the cleanup, though professional contractors were hired to sanitize the buildings and help them meet health and safety codes.

“The school was in bad shape,” Ordoyne tells her history students. “All of your teachers … were cutting trees and hauling trees, bleaching walls, picking up things that we never ever thought that we would have to pick up.”

The first week of school, contractors are still on the nine-building campus, with their efforts focused on one building that remained closed and another that is only partially open. In addition, more than 150 state and local police from New Jersey—in the area to help with the local relief efforts—are still staying in the gymnasium, and using half the cafeteria for dining.

For Ordoyne, Katrina calls to mind another big storm, Hurricane Betsy, which hit the area when she was a teenager back in 1965. She lived at the time in what she describes as a “typical old New Orleans home” on St. Patrick Street with her parents, two brothers, and a sister.

“I can remember the house just rattling, and the wind just blowing and howling and making these screeching, high-pitched sounds,” she says.

The shingles from a neighbor’s house crashed through her family’s windows.

“I can see it as if it were yesterday, those red-clay shingles just like knives in the wooden floor,” she says.

This time, Ordoyne’s home in nearby St. Charles Parish suffered only minor damage. But she lost at least one thing of great personal value. Katrina leveled three pear trees in her backyard planted years ago, one for each of her daughters.

‘I Dreaded Today’

Many of the 664 students who showed up the first day at Bonnabel—less than half the usual population of about 1,600—had been through a month of upheaval: packed into small hotel rooms in unfamiliar cities, staying at the Astrodome in Houston, moving from city to city, returning in some cases to see their homes unlivable and their parents out of work.

“The hurricane, the natural disaster, is over,” says Jo Ballantine, Bonnabel High School’s social worker. “But there is, I think, a hurricane inside of each one of us.”

Bonnabel serves a diverse enrollment, with many students from low-income families here in Kenner. Almost half the students are African-American; about one-third are white; one quarter are Hispanic or Asian.

About two-thirds of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunches. Most of the more affluent families here, including many in the neighborhoods right by the school, send their children to private schools.

Regjon Lee, a 10th grader, says she spent “four strong, hard weeks” in Baton Rouge after the storm. She slept on the floor in a Motel 6 in Baton Rouge with seven family members, all in the same room.

Karen Villegas, a junior at Bonnabel, traveled to Houston with her extended family—parents, siblings (including a pregnant sister), her aunt, and her grandmother—where they stayed in a trailer.

She attended a Houston public school for about one week.

“I didn’t like it,” she says. “I didn’t really have any time to get accustomed, so it was weird.”

She still can’t stay in her home, which sustained heavy damage.

Leigha Cooley, another junior, says she doesn’t feel quite right. With her, it isn’t so much what she lost. Her trouble seemed akin to survivor’s guilt.

“I didn’t lose anything, and a lot of people did,” she says.

Angela Carrillo, another 16-year-old junior, says she worried about what she would find on her first day back to school.

“I dreaded today,” she says. “I was scared to come back and see who’s not going to be here.”

At Solis Elementary, emotions also remain fragile the first week of school.

Teacher Camelia H. Hinojosa has put up a map in her classroom where her 3rd graders can mark places they stayed during and after the storm: Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Texas, and Lake Charles, La., to name a few.

Hinojosa says she is staying with a cousin, since her home is not yet habitable. She lost not only her home, but also her portable classroom.

“All of the children’s things, according to the National Guard, had to be thrown away,” she says, adding that she isn’t ready to let the students see their old room yet.

“You’ll understand when you see it,” she explains, starting to tear up. “It was upsetting to me.”

The portable, under lock and key, is a mess, with moldy walls, debris scattered across the floor, and a gaping hole in the ceiling exposing bare sky above.

Another portable at the school, meanwhile, seems frozen in time.

A message on the whiteboard from Aug. 26, the last day of school before the storm, reads: “The weatherman says we will feel the heat as much as had been over the weekend. Hurricane Katrina is in the Gulf and the Weather Center is keeping a close watch on her.”

On one wall, a giant purple octopus keeps an eye on the classroom, but the decoration can’t be saved because it’s covered with mold. “The kids called him Ollie,” says Sheila Adams, who taught special-needs students in the room. “He was usually the first thing I saw in the morning when I opened the door.”

The records clerk at Solis Elementary, April W. Stock, also suffered a loss after the storm: Her home was looted, including her 16-year-old son’s life savings of $157.

“I don’t know if you can put a monetary value on it, but I lost my sense of security,” she says.

Job security is another problem for many school employees. If not enough students return, the district will likely have to lay off staff. “Right now, I actually have too many teachers,” says Ronald P. Ceruti, the district’s assistant superintendent for human resources. “If we don’t get those kids, then you don’t get the money.”

‘This Is Your Catastrophe’

Back at Bonnabel High on day three, Ordoyne is already diving back into the curriculum. She is giving one of her U.S. history classes a quiz that day, and is planning another for the following day.

Most kids, she said, aren’t able to do homework outside of school, because they are helping rebuild their families’ houses, are piled into close quarters with many relatives, or are holding part-time jobs.

Still, she says, most of her students are “really good.”

“Every now and then, I’ll have one that drifts off, or starts to cry, and I tell them: ‘You know what? If you have to cry, cry,’ ” she says. “I’m trying to help them cope.”

Part of that effort is helping her students realize that they’re not the first ones to weather a disaster.

“As we talked about the Great Depression in history, that was not your reference, so you didn’t know the sacrifices that that generation made,” Ordoyne tells them the first day back to school. “You didn’t realize how strong a character it took to pull together to rebuild after the Great Depression.

“Now it has happened to you,” she continues. “This is your catastrophe, and as you grow older, grow into adulthood, you’ll talk about this for years to come, and you’ll tell people: You haven’t experienced anything. I survived Katrina.”