Corrected: Clarification: The story implies that three unaccredited schools mentioned in the report are diploma mills. Unaccredited schools are not necessarily diploma mills.

Experts say federal efforts to investigate “diploma mills” may eventually help educators purge their ranks of people who hold bogus degrees.

Those efforts were stepped up last week, when a report on the problem was released and discussed at a hearing of the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee. Among other troubling findings, the report found that some Head Start programs around the country had used federal money to pay for degrees from diploma mills, which require little, if any, academic work and are now primarily offered online.

Read “Diploma Mills: Federal Employees Have Obtained Degrees from Diploma Mills and Other Unaccredited Schools, Some at Government Expense,” from the General Accounting Office. (Requires Adobe’s Acrobat Reader.)

The report, produced by the General Accounting Office, the investigative arm of Congress, also found that at least 463 federal employees, some in the upper ranks of government, held bogus degrees from diploma mills. Two of them work for the Department of Education.

But Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, who chaired the Senate hearing, said she believes those numbers largely underestimate the scale of the problem.

“This is the tip of the iceberg,” said Sen. Collins, who noted that the probe targeted only a few out of the scores of diploma mills, and that 330,000 federal jobs require some sort of degree or completed coursework.

Others pointed out that the problem goes way beyond federal employees. (“Educators’ Degrees Earned on Internet Raise Fraud Issues,” May 5, 2004.)

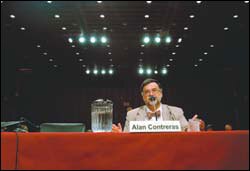

Alan L. Contreras, the administrator of the Oregon Student Assistance Commission, which tracks the diploma mill problem, testified at the hearing that he believes K-12 teachers and administrators are among the most common professionals to obtain such degrees. (“Evaluator Reverses Position on Degrees From Saint Regis,” this issue.) In an earlier interview, he said skills in education, like those in police work, corrections, and counseling8#151;other prime fields for bogus degrees—are easier to fake than those in technical and scientific fields.

Nearly 150 diploma mills, including all of the institutions identified as such in the GAO report, are on an official list of diploma mills maintained by Oregon’s Office of Degree Authorization in Eugene, Ore. That state is one of a few states that have made it a crime to use a diploma mill degree.

Tagging Bogus Degrees

Though the term was coined in the 1920s, diploma mills have in recent years gone virtual, as online learning has become a popular way for Americans to have easier access to educational programs, experts say.

In the probe, GAO investigators asked four unaccredited schools for information about their graduates. Three complied. And that’s how they found the 463 federal employees who had gotten bogus degrees.

|

| Alan L. Contreras, the administrator of the office of degree authorization at the Oregon Student Assistance Commission, testifies at a U.S. Senate hearing last week in Washington. Mr. Contreras has tracked the growth of diploma mills, which offer academic degrees for little, if any, work. —Photograph by Allison Shelley/Education Week |

Robert J. Cramer, the managing director of the GAO’s office of special investigations, underscored that those numbers represent only the three schools: Kennedy- Western University, California Coast University, and Pacific Western University.

GAO investigators also looked through the personnel files of eight federal agencies, including the departments of Education, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, and Transportation.

GAO investigators found that 28 high-ranking federal officials, at the GS-15 level or above on the federal job scale, held diploma mill degrees.

“We believe that is an understatement,” Mr. Cramer said.

Officials with bogus degrees include managers in the Department of Energy and in the National Nuclear Security Administration, and senior executives in the departments of Transportation and Homeland Security.

The GAO did not release the names of the employees who have diploma mill degrees, but it has provided them to the agencies’ inspector general offices, Mr. Cramer said.

In interviews with six of the employees and their managers, GAO investigators were told that “experience, rather than educational credentials, were considered in hiring and promotion decisions” concerning those employees.

Investigators also requested financial records from the four schools that they said were diploma mills; two complied.

Data from just those two schools —Kennedy-Western University and California Coast University—revealed nearly $170,000 in tuition payments from the federal government for more than 64 federal employees.

But Lewis M. Phelps, a representative for Kennedy-Western University in Los Angeles, who attended the hearing, defended that institution. “I’m not pretending that they’re Harvard, but they’re not a diploma mill,” he said.

Head Start Links

Investigators also found checks that indicate that recipients of Head Start grants have used federal funds to pay for courses at diploma mills.

|

| U.S. Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, chairs a Governmental Affairs Committee hearing on bogus degrees awarded to federal workers. —Photograph by Allison Shelley/Education Week |

Sen. Collins said she was surprised when investigators turned up three checks to diploma mills from federal Head Start grantees in three different states.

“We didn’t expect to find this; we were looking for federal checks going from federal agencies to diploma mills,” she said.

At the hearing last week, Sen. Collins said diploma mills pose “problems on many levels,” such as by devaluing legitimate degrees and impugning legitimate universities that have similar names; giving diploma-mill degree-holders unfair advantages for promotions; and, in some cases, giving unqualified or dishonest employees authority in sensitive federal jobs.

The senator called on the federal Office of Personnel Management and the Education Department to close a loophole in federal regulations that allows government employees to pay for courses from unaccredited schools with federal money.

“What looks at first to be a clear rule prohibiting agencies from paying for diploma mill degrees is, in reality, subject to a loophole that can be easily exploited,” Ms. Collins said. “The loophole allows agencies to pay for classes at diploma mills. It must be closed.”

Sally L. Stroup, the Education Department’s assistant secretary for postsecondary education, told the hearing that the department was developing an online list of properly accredited institutions. The list would give employers and prospective students easy access to information about accredited learning institutions.

But Ms. Stroup said such a list was not a complete solution, in part because some unaccredited institutions offer high-quality educational programs.