Teachers often look back on their careers, wondering if they’ve made a difference. I write this from rural western Massachusetts, where I am not teaching at the moment. (I’ll return to the profession, I’m sure, when the time is right.) Instead I am looking back on a job I had six and a half years ago, as a shift leader at a school for juvenile delinquents on a small island off the coast of Cape Cod.

The island, a 75-acre crescent called Penikese, seems idyllic from afar. It rests in the blue-green waters of Buzzards Bay, 12 miles south of Woods Hole near the end of the Elizabeth Islands, and serves as a refuge for troubled young men. For me, the Penikese Island School is a place (and every teacher has at least one) where I found out something about who I am.

Published three years ago, my book, Crossing the Water, chronicles my first 18 months there, as a teacher. But it doesn’t cover my final six months as a shift leader, which came three years later. That stint, and a particular kid I worked with, are what I’d like to recount here, along with some observations about how the school has changed.

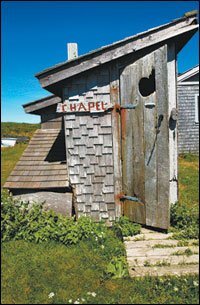

Picture Scotland, if you will, islands like Mull or Skye, and you’re getting close to what Penikese looks like. It doesn’t have the high cliffs or the deep waters of those places, but it has something of that feel—isolation, exposure to the sky, and the constant presence of the sea. The island has been used variously as a seasonal fishing camp (by Native Americans), a home to early settlers (who farmed and grazed sheep on its meadows), a retreat by a wealthy New York financier, the site of a summer school for biology, and a leper colony, from 1906-22.

After the lepers were transferred to Louisiana, the buildings on the island were dynamited, and Penikese was left to the wind and the birds until 1973, when George Cadwalader, an ex-Marine who’d served in Vietnam, convinced the state to allow him to start a private school for teenage kids in trouble with the law. In exchange for the use of 11 acres, the school now serves as steward to the remaining 64 acres of sanctuary, which is home to many animals and birds, among them terns, snowy owls, and Leech’s storm petrels.

The school’s onshore office is in Woods Hole, a village bordered on three sides by the sea. It has a four-room elementary school, a general store, and a post office where a letter addressed simply to “Dan Robb, Woods Hole,” will find its destination. It is a peaceful place once the tourists leave in the fall.

When I was a kid there, riding my bike home from the pharmacy with some gum in my pocket, I’d often see a few tough boys I didn’t recognize walking the streets. Close behind would be Cadwalader or Dave Masch, a local biologist and the co-founder of the school. Their vision, in those heady days of the 1970s, was to have a school community the size of a large family that took troubled teenagers out of their usual environments and put them on the island.

Penikese is a nonprofit that, early on, contracted almost exclusively with the Massachusetts Department of Youth Services and its Rhode Island equivalent. Eight boys convicted of crimes ranging from shoplifting to grand theft auto were offered the option of a six-month stay at the school instead of jail or a foster home. And they lived vigorous lives. Academics were taught every weekday in the one-room schoolhouse, and skills such as gardening, carpentry, lobstering, cooking, and animal husbandry were learned as part of survival on the island. There were chickens for eggs and a few pigs as pets.

In the early ’90s, Cadwalader explained the system to me, saying, “What we try to teach ... is that there is a direct relationship between what one does and the reality one experiences as a result. If we don’t chop the wood, the house is cold and meals can’t be cooked. If we don’t heat water on the stove, we can’t take a shower. If we don’t feed the animals, they go hungry. If we don’t build community, we have none.”

I experienced this firsthand, for two and a half years, while I did stints as classroom teacher and carpenter on Penikese. Then I moved West and spent three years in café-dappled Seattle, working on my book and pounding nails for rent. After returning home, I needed work, so I called the school to see if they had any.

They did, but I’d never before been shift leader, the head disciplinarian. I knew the ropes. I knew when a kid called you a son of a bitch (or worse) that it probably wasn’t you he was seeing but just another adult who was either going to disappoint him or punish him for all he’d done wrong. I knew how to see the students’ anger and pain for what it was. But was I up to the task of being alone at the top? When that boat left Penikese, not to return for at least a week—man, it really went away.

I said yes in the end. I think I needed to feel again that my work was worthwhile. And I needed to see whether I had what it takes—both the strength and the patience to deal with those whom everyone else sees simply as “juvenile delinquents.”

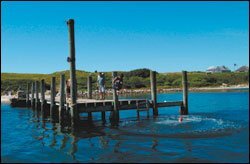

On a Thursday in mid-April in 1998, I found myself on the school’s boat, the Harold M. Hill (named after a generous donor). We’d chugged three miles down the rocky western coast of the Elizabeth Islands—by turns heavily wooded and laced with meadow, all crossed by low stone walls—when Penikese began to lift herself out of the sea beyond the starboard bow. Four miles farther, she was an undulating silhouette, and by the time we’d gone 10 miles, details of her 75 acres stood out. Two sharp stones sat near the top of the high hill, and at the hill’s base stood a plain-looking house with a red door in the middle. The stone pier reached out into the cove, and two small boats, one red, one black, rested on the beach, ready for lobstering. The hay meadows and the pig yard were visible beyond the house.

And then we were at the dock, where a kid in jeans patched with duct tape was yelling down to us, “Hey, suckuhs, welcome to Fantasy Island.”

The next thing he said was, “Throw your bags on up.” I did, and clambered up the ladder to the dock.

I remember feeling odd. Soon the boat would go, and with it the guy I was relieving, and the island would be my realm. I could rule as I chose. The water was so clear and blue along the pier. I stared into it as I took a few steps toward the beach. Of course, I could also be deposed, perhaps by force, I reflected.

“So, you’re the new shift leaduh,” the kid said in a thick New England accent.

I looked him straight in the eye and put out my hand.

“Good to meet you. I’m Dan.”

There was a pause, as he looked at my hand for a moment, a tall, skinny kid with big ears, and either tried to remember the etiquette of a handshake or wondered if he would regret our meeting.

“Jarod. It’s good to meet you, too,” he finally said, taking my hand in his and gripping it hard. His lip curled under his light mustache as he spoke, as if he might not mean it.

“How long you been here?” I asked.

“Ah, man, too frickin’ long. Foah months. I’m second-longest out heah. I’m due to go home in eight weeks. Evuh seen a place like this?”

“I used to work out here. I was the boat-builder guy, and before that I was the teacher.”

“The teachuh? We already got one of those. One too many of those.”

As we talked, I watched him looking me over. He took in my height, weight, stance, how my eyes met his, whether I looked scared—which was how I felt. Not because I was intimidated. I’d worked with many kids like him, bigger than him, angrier, less predictable. But as the teacher, I’d always had the shift leader to back me up. Suddenly, as the one in charge, I had to be the calm person, a combination of Clint Eastwood and Mother Teresa.

“You gonna drive the tractuh up?” a voice asked from behind us. I’d been so intent on Jarod, I’d failed to notice another kid walk down the pier.

“Nope,” said Jarod. “Hey, yo. This is the new shift leaduh.”

The second kid swung himself into the tractor’s driver’s seat. He grunted, “How’s it goin’?”

“Going well.” I stuck out my hand to shake his. “What’s your name?”

“Earl. What’s yoahs?”

As I told him, he shook my hand hard. Then he started the tractor and began to drive slowly up the pier.

“So, what’s the scoop with you?” I asked, walking next to him.

“Scoop?” He wore an Orioles cap turned backward and looked, with that scowl he wore, as if he were 40. I knew he couldn’t be more than 16.

“If you wanted to tell me something, that would help me understand you,” I explained.

He hunched over the wheel for a moment, and then said, “Hey, pal. Don’t get loud with me.”

“Don’t get loud?”

He nodded. Soon we were halfway to the house, the tractor swaying up the rough lane I’d walked many times before. Coming toward us was Ben, the departing shift leader. He was taller than me, broader of shoulder, and a couple of years younger. We stopped to talk where the track widened by the carpentry shop, and Earl and Jarod went on to the house. I asked Ben if he could fill me in on the students, but he was in a rush, so he told me that Rachel, the shift’s teacher, could help me out. We shook hands, and he headed down the wagon path.

I hustled up to the house and got Earl to give me a hand getting my bags inside. Rachel was in the kitchen, stoking the big cookstove. She had the fire roaring and was heating a pot of coffee.

We sat down at the rough-hewn dining table, the “board” where many of the school meetings take place. In her late 20s, with light-brown hair and a ready smile, Rachel gave me her report on the boys in low tones so that no one else could hear.

“Bill is smart, impulsive. He often doesn’t seem to have a check on his impulses. Earl is also quite smart and is beginning to flourish in school, but probably once a day, he goes nuts. When that happens, Marty [another shift leader] or Ben just has to sit on him.”

“Sit on him?”

“Well, they just wrap him up in their arms until he calms down.”

Shit, I thought. I can do that, but I don’t like it.

“What else?” I asked.

“Well, Jarod and Brian just got caught dealing weed one too many times. And then there’s Danny. He’s thoughtful, but he’s unpredictable when he’s feeling down, which is about once a day.”

“And what about our co-worker, Matt?” I asked. Matt was a junior counselor.

“He’s a good guy. He’s young, and I don’t think he sees very far into these guys, but I like working with him.”

So I’d learned that there were only eight of us—five students (three fewer than normal) and three staff. This was due to the rolling admissions process, in which the school at times found itself down a few students, depending on who’d been thrown out or sent back to jail. It wouldn’t take too long, however, for new students to come on board.

I grabbed my bags and headed through the rustic living room, which was given an air of solidity by the great posts (salvaged from wrecks along the shore) that supported the floor above. I found Bill and Earl upstairs and chatted with them a bit before stowing my bags in the staff dorm room. Later the three of us split wood for a couple of hours, then went for a walk to the leper cemetery, a plot of 16 graves hard by the sea at the north end of the island.

By the end of that first day, I felt pretty calm. I had met all the boys and Matt. Things were rounding into shape. We had an uneventful evening. Matt prepared dinner—roast beef, potatoes, salad, and fresh bread—and the boys seemed normal. I slept well that night, only waking twice as someone headed out to pee. I heard their footsteps going and returning.

During the next few days, I settled into the everyday rhythm of Penikese: Rise at 7:30; calisthenics; breakfast; schoolwork; break; more schoolwork; lunch; more schoolwork; outdoor work; break; dinner; homework; relax; bed. Things had a flow, and the weather was good. The adults work in shifts—one week on the island, one week off. And on Sunday the second shift arrived around noon, so Matt, Rachel, and I went home. We parted ways at the dock in Woods Hole, knowing we’d reconvene in a week.

Which we did. And when we got back onto the Harold M. Hill, there was a surprise passenger on board: Howard. I introduced myself to him, a tough-looking, quiet kid with a crew cut. He croaked “What’s up?” then turned back to steering the boat under the guidance of the captain. We had an uneventful ride—the day was calm, and the islands slid by like film shot from a slow train’s window.

I wasn’t made of wire thick enough to ground all of the anger and disappointment of these kids indefinitely.

And then we debarked at the stone pier, and the water along the beach was green and clear, and the tractor lurched up the hill. We were alone again. We fit ourselves to the schedule, and Howard seemed to work in reasonably well.

Then, on the second day, as we played touch football before breakfast, out in the hayfield, things began to fall apart.

First, in the huddle, Bill told Danny that Howard had called him a fag. Although Howard had said no such thing, Danny believed Bill and started talking trash. Finally, on third-and-long, Danny threw a haymaker at Howard as he tried to run a buttonhook past him. Remaining calm, Howard dodged the punch and met Danny’s chin with a straight right of his own. Danny went down in a heap. I sent the rest of the boys in with Matt for breakfast and wrapped Danny in my arms to keep him from making good on his threat to “cut his heart out with my fishin’ knife.”

Once he’d stopped struggling and calmed down, we talked for a moment.

“Danny, the kid just got here. Don’t worry about what he says, all right?”

“All right. But keep him the hell away from me.”

I knew I couldn’t do that on the island—which was part of its power. But what I hadn’t counted on was Earl.

In the afternoon, after work was done, Bill and Earl went for a walk to the pier. Twenty minutes later, Earl returned, banged the door open, took a seat at the dining table, and put his head down on his arms.

“What’s up, Earl?”

“Nothin’,” he growled. “My head hurts. My knee hurts.”

“Why don’t you take a nap?”

“Nah,” he said. “Punks take naps. Freakin’ Bill is a freakin’ numb nuts, makin’ stuff up.”

Just then Bill came through the door and began to head upstairs. Earl was up in a flash.

“Hey, Billy, why you such a freakin’ punk?”

“What are you talkin’ about, man?”

“You know what I’m talkin’ about, bitch.”

“Yo, Dan,” Bill said to me, at which point Earl jumped at Bill and put him in a headlock. There was a scuffle. After 30 seconds or so, Bill was free, unhurt, and upstairs, and I had Earl in a soft restraint.

“Let me go,” was what he said for the next 10 minutes.

“I will once you calm down. You calm down, and we’ll talk this out.”

Fifteen minutes after the fight had begun, Earl and I were standing on the high hill. His face was still dark, his hat pulled low so the brim shaded his eyes.

“What was that all about, man?” I asked him.

“Bill was ticking me off real bad, asking me all kindsa questions about my family. I told him to shut the hell up, but he kept on ... ”

Earl was a smart kid. One day, when we were putting a sister frame in one of the boats, he suggested how best to drill holes for the new screws. And he was right. But he’d grown up in foster homes, for the most part, and it seemed that in several, the parents were screamers. So he had an aversion to loud voices. I also gathered that he’d basically been on his own since he was a young boy. When he wasn’t in a foster home, he was raised hardly at all, with a backhand to the head for “no.” Either that, or he’d get thrown out of the house. So, he’d gotten in trouble—stealing cars, raising hell, and losing hope. I wanted to lead him the other way.

So I asked, “You and Bill are good friends, right?”

“Yeah,” he said. “We’re tight, but sometimes he pisses me off.”

“You think it had to do with Howard and Danny’s fight?”

“Nah, those two are just punks. I got no problem with them.”

We weren’t close to resolving anything, but Earl had calmed down. I told him I’d have to consider sending him off the island if he got in another fight. Later I called Pam, the school psychologist, who worked at the office onshore, to see if she could help Earl get through his problem.

“What I’m thinking is, something external set Earl off, and if I could get him to recognize it, we might be able to calm him down some,” I told her.

“Well, you’re on the right track,” she said, her voice full of reassurance. “Earl feels, when trouble’s brewing anywhere, he’s to blame. If something reminds him of home when he was growing up, like yelling, and he feels he’s to blame, he’ll probably flip out and tackle someone—that’s his MO. You think you can work with him on that?”

I told her I’d try.

That night, after dinner, I spoke with Earl on the deck as we drank cups of tea and looked out over the cove in the failing light. The wind was calm, and we could hear small waves coming onto the shore. I told him I’d talked to Pam.

“She said that sometimes when things hit the fan, even if you aren’t involved, you feel like everything’s blamed on you. Is that right?”

Earl looked across the cove for a few moments, his eyes wide, as if he were seeing something out there. “What the freak you talkin’ about, Dan?”

“She said that sometimes, if things are going bad around you, you feel like it’s all on you, and you bug out. True?”

“I don’t know what the freak you’re talking about.”

“OK. Let’s say that sometimes, like when Howard decked Danny, you have nothing to do with it, but you still feel like the blame’s on you. Then what? You feel bad, and then you rumble with your pal Bill. Let’s just say that could happen. All right?”

He nodded to me, and I could hear an airplane far overhead, flying southeast toward Martha’s Vineyard.

“OK,” I said. “When something like that happens, we’re going to say, ‘There’s a squall coming.’ ”

“What’s a squall?”

“A squall is a short, intense storm that comes fast and is real strong, and then it passes. Just like your anger yesterday.”

“A squall,” he said. “I ain’t heard that word before.”

“It’s an old word. But one other thing.”

“What?”

“You know how you always wear your hat?”

“My Orioles hat? The O’s are the shit.”

“Yes,” I said. “Well, this is what I want. I want us to have a signal. When you’re beginning to feel things are going wrong around you, you come and find me and tell me, ‘Dan, there’s a squall coming.’ And when you feel that way, wear your hat backwards. When you feel good, after we talk and get things straightened out, I want you to wear the hat forwards. All right?”

“All right.”

The house was calm that night.

But I wasn’t. I was thinking about Danny, what he might do to Howard, and about Bill, who seemed to relish creating strife. I tossed in my bunk, listening for footsteps, and finally fell asleep for a little while just as the horizon over by Cuttyhunk began to lighten.

The next day, we got up and did it all again, and things were calm until Friday, when Earl had another meltdown, this time after Brian dumped a bucket of lobster bait on Jarod’s head. But we got it straightened out, and Earl got his hat turned forward. And I never had to sit on him again.

Over the next month, he mostly wore his hat forward, except on six occasions. Relatively speaking, he had a month of good days. He was on the way.

I, however, was not doing so well. Over the weeks it took to deal with Earl’s problem and give him some tools to work on it, I lost ground. Most of the kids weren’t as easy to talk to as Earl. He was tough and troubled, but at least he was accessible. Most of the other students were harder to read, more intimidating, and a couple were more threatening. Small conflicts were constant. As May turned into June, I felt my patience waning, my resolve flickering. I wanted out. And I count this as something of a failure.

With help from the rest of the staff, I did get Earl through the end of his term. He made his grades, passed his tests, didn’t wallop anybody. His family came out to the island in June and saw him get the certificate awarded to those who complete their coursework and abide by the rules. From what I hear, he later graduated from high school and is doing well now, five years later. He works in construction and has a family. If I helped him, I’ll count that as a success.

But in the end, I decided to leave Penikese. Once we were up to eight boys and four staff again, which happened soon after Earl’s departure, once the school was ticking along on its own, it was time for me to go, six months after my return. I love the place—don’t get me wrong. So many things are right about it. It’s a school that believes in dealing with kids individually, that puts tough teens into a highly structured environment where they’re forced to work on relationship and living skills. It truly rehabilitates the child. But I needed to be out in the world again.

I had discovered something about myself. I could be hard enough, and grounded enough, to be the shift leader, to do it at least competently. But I wasn’t made of wire thick enough to ground all of the anger and disappointment of those kids indefinitely. I had begun to short- circuit in that little world, to miss space and a larger community and a room where I could shut the door. I missed ... normalcy.

But there was something else I’d found. When I first worked on the island, as a teacher, the anger and abuse the boys flung at the staff seemed nonsensical to me. I took it personally. Earl showed me how really logical his anger was—he’d been through hell—and how treatable. That meant I could let his anger be his, which in turn allowed me to be clear about my own response to it.

Not long ago, I returned to the island for a visit, as I do periodically. The students have changed little. They’re still troubled, and Penikese still does a fantastic job at moving them toward competence in our complicated world.

Some things have changed more, of course. When I left the school, Prozac and Zoloft were just becoming popular, and only a few kids had been diagnosed with learning disabilities or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Now it seems they’ve all been diagnosed, which I suppose is good in some ways. Still, it seemed to me that many boys learned better, and exhibited less attention deficit or hyperactivity, once they’d been on the island for a while. There, they watched no TV, ate well, and were subject to little external stress. They worked hard and slept hard. They had a chance to be kids. That hasn’t changed.

It’s a school that believes in dealing with kids individually, that puts tough teens into a highly structured environment where they’re forced to work on relationship and living skills.

The school also now makes talk therapy part of the curriculum, along with increased academic rigor. Which is good. And the house has been expanded, a building or two added. The student body has changed some, too, in that most students are not adjudicated but are either foster kids, handled by the department of social services, or are students (from public schools across Massachusetts) too disruptive to remain in mainstream classrooms. They tend to stay for as long as nine months, and they tend to stay out of trouble once they leave.

On my recent return, I talked to the school’s current director, Toby Lineaweaver. I asked him what he thought was important to communicate about Penikese.

“Well, we’re a one-kid-at-a-time program,” he said. “That’s the most important thing.” He went on to say that people are beginning to wake up to the truth about programs like Penikese: They work. They cost more in the short run than warehousing youthful offenders, he added, but their recidivism rates are five or six times lower than typical juvenile jails. This is being borne out in Missouri, he said, where the entire youth corrections program is constructed on a model similar to the Penikese Island School.

As I rode back to Woods Hole on the boat that day, I reflected on how much I owe Penikese and the boys I worked with. I hope I did them some good. Someday, perhaps, I will hear the call again and return for a year or two.

For now, when I have a tough day or a disappointing interaction, if I’m wearing a baseball cap, I work hard to turn it forward.