Fights over religion in public schools are not new. But several Republican-led states are testing the limits through initiatives that seem primed to land before the U.S. Supreme Court, seeking to reshape how faith and schools intersect.

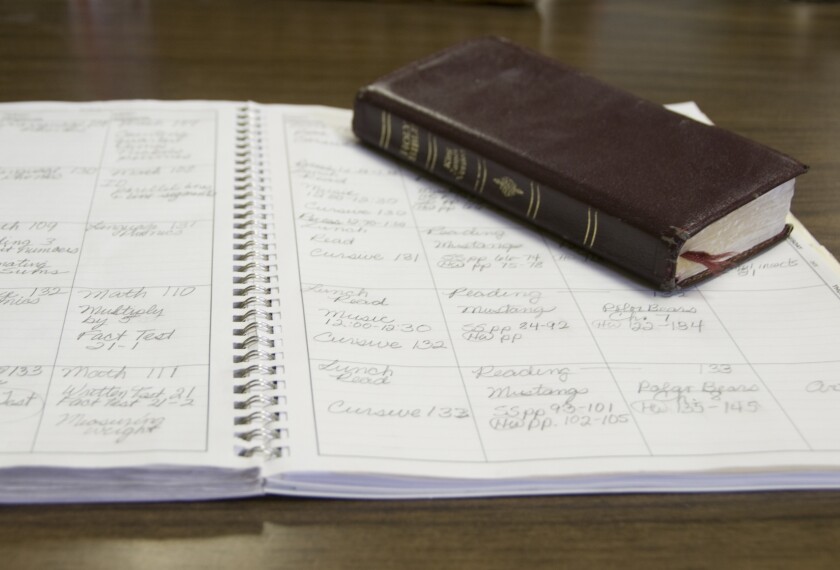

Texas on Friday became the latest state to infuse religion into instruction, with the state school board approving a controversial curriculum with Bible-infused lessons for elementary schools. It comes amid a wave of related measures in nearby Republican-led states, with Louisiana passing a law requiring all public school classrooms to display the Ten Commandments, a mandate in Oklahoma ordering teachers to include the Bible in lessons, and Oklahoma’s approval of a virtual charter school run by the Catholic church.

Oklahoma’s state superintendent, Ryan Walters, also recently announced the formation of an office of religious liberty and patriotism within the state education department and required that schools show a video announcement of the new office, in which he prays for President-elect Donald Trump.

Even though both Louisiana and Oklahoma have seen challenges in court—a judge blocked the Ten Commandments law for being “unconstitutional on its face” and Oklahoma’s supreme court ruled against the religious charter schools—experts say the political climate is becoming more favorable toward such policies. Trump has been supportive of prayer in schools and offered support for the Louisiana measure.

Historically, attempts like this aren’t unusual. But experts say the recent measures could be teeing up efforts to go before the U.S. Supreme Court. The court’s conservative majority has been paving the way in recent years for public dollars to go toward religious schools and ruled in favor of a football coach’s post-game prayers at midfield.

“I imagine legal scholars would say it’s kind of an uninteresting case from a legal perspective because it seems like the law is clear,” said Suzanne Rosenblith, a professor at the University at Buffalo, SUNY, who specializes in education politics and legal issues. “This court hasn’t appeared to show a lot of deference to precedent in cases that have nothing to do with religion, so I think it could be interesting.”

This isn’t the first time leaders have tried to bring religion in public schools

Every once in a while, there are “spurts” of similar measures that aim to bring religion into schools, said Rosenblith.

“These things flare up and then they kind of die down,” she said.

In 2005, Kansas approved curriculum standards that were skeptical about evolution. In 2006, lawmakers in Georgia passed legislation that would allow classes on the Bible’s influence on literature, law, music, culture, and other aspects of society; critics worried it didn’t have safeguards to keep it from straying into the unconstitutional. And back in 1978, Kentucky lawmakers passed a law similar to the Louisiana bill that passed earlier this year requiring a Ten Commandments display in each classroom.

Religion in schools has been litigated since the mid-20th century, with courts finding required devotional readings of the Bible and the offering of the Lord’s Prayer to be unconstitutional, as is religious instruction in classrooms, though schools can’t prevent students from praying independently as long as it doesn’t disrupt school activities.

The Supreme Court also found in 1980 that the Kentucky Ten Commandments law was unconstitutional.

But more recently, the Supreme Court has paved the way for increased mixing of religion and public schools, including through programs that allow parents to direct public funds toward private schools.

In 2020, the court ruled that a Montana tax-credit scholarship program couldn’t bar families from using the scholarships at religious schools. And two years later, the court said Maine couldn’t exclude religious schools from a public tuition program for towns without public high schools.

Private school choice over the past few years has grown into a top-ticket priority for the Republican Party.

Twelve states now have at least one private school choice programs that’s available to all K-12 students in the state or is on track to be, according to an Education Week analysis. And private school enrollment in the United States is overwhelmingly religious: In 2021, three-quarters of children attending private schools attended a religious school, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Now, state-level momentum for using public funds for private school tuition could translate into federal momentum. In announcing his pick for education secretary, Trump wrote that Linda McMahon would “fight tirelessly to expand ‘Choice’ to every State in America, and empower parents to make the best Education decisions for their families.” And that fight could be aided by growing Republican support for private school choice and Republican control of both chambers of Congress.

Is there a way to grapple with religion, without it being devotional?

There is a lot of religious illiteracy, Rosenblith said.

But teacher-preparation programs don’t prepare educators to talk about religion in class. In some ways, that’s missing an opportunity to help build students’ understanding of why people believe what they believe and where those beliefs come from, she said.

“We’d be more religiously literate, both of our own faith communities and others, and perhaps we’d be more tolerant and understanding of other people’s comprehensive world views,” Rosenblith said. “I don’t think you get any of that with some of the things that are gaining attention right now and will probably find a hospitable home in the courts.”