It was supposed to be the spoonful of sugar to make a bitter medicine—the loss of teacher tenure—go down easier. Instead, a pay mandate in North Carolina has ignited debate about a recent law’s ramifications for the quality and stability of the state’s workforce.

As the Tar Heel State lurches toward the employment overhaul, required under a 2013 measure, districts must offer four-year contracts worth $5,000 in additional pay to a quarter of their teachers by July 1. Lawmakers hope the promise of a raise will persuade eligible teachers to relinquish tenure voluntarily before it disappears for all in 2018-19.

From the looks of things, it won’t be that simple.

Administrators’ and teachers’ associations alike are protesting the 25 percent quota as unnecessarily divisive in a state where salaries have been all but frozen since 2008. Some districts are requesting extensions in meeting the mandate; others are vowing not to carry it out; two are suing to overturn it.

“At our countywide meeting, the district’s chief counsel got up and said, ‘There is no fair way to implement this requirement,’ ” recounted Benjamin C. Owens, a seven-year physics and mathematics teacher in the Cherokee County district in rural Murphy, N.C. “That to me spoke volumes about some of the issues we as teachers have brought to the table with this bad legislation.”

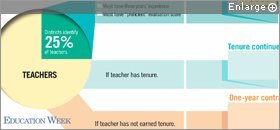

The changes in North Carolina are the products of a 2013 budget measure that does away with the state’s tenure rules. Under the new policy, all teachers will be instead placed on one-, two-, or four-year contracts beginning in 2018-19, making it far easier for districts to dismiss them.

The next few years are a run-up of sorts, during which lawmakers hope to encourage teachers to transition voluntarily. The carrot: four-year contracts, worth an additional $500 in base pay each year, awarded to teachers who agree to give up tenure.

Districts charged with implementing that mandate argue that it is simultaneously prescriptive and vague. It specifies, for instance, that only a quarter of teachers can be offered the four-year contracts and salary increases. Eligible teachers must have taught for at least three years in the district and garnered satisfactory reviews. But beyond that, the law is silent on how superintendents and boards should identify the teachers.

It also comes during a drop in the state’s teacher salaries relative to its neighbors. According to National Education Association tables, North Carolina teachers’ wages have tumbled from 25th among the states in 2007-08 to 46th in 2012-13. The average teacher in the state now makes about $46,000.

For years, merit-pay plans have proved difficult to implement because of disagreements within the profession about how to identify top teachers.

To that, the North Carolina requirements have the added complication of surprise. They were last-minute additions to the budget bill, leaving administrators just a year to devise criteria that meet the letter of the law.

Preserving Career Status

In theory, some administrators embrace the idea of getting rid of tenure: The state’s school boards association adopted that position a few years ago. But even its supporters felt that teachers who already had earned career status should be allowed to keep it, and that the pay plan has muddied the discussion.

“Across the board, most school board members want to be able to make sure all teachers are getting increases in their compensation,” said Leanne E. Winner, the director of governmental relations for the North Carolina School Boards Association. “Many districts feel that they have more than 25 percent of their eligible teachers who are performing well and should be eligible for the raise.”

There are no overall patterns among districts’ selection criteria, according to lawyers helping the state’s 115 districts devise the so-called “25 percent” plans.

Some are selecting 25 percent from each school, others from the district at large. Some are using mostly performance-based criteria, others are saving slots for teachers in shortage subjects, said Richard Schwartz, a partner at Schwartz & Shaw, in Raleigh, N.C., which represents some 45 districts.

There is one common element, though. “There has been pretty universal disdain for the whole process,” Mr. Schwartz said.

Concerned about grievances or litigation, some districts are writing criteria with an eye to protecting themselves. A handful, for instance, are incorporating a random lottery into their selection criteria, said Dean Shatley, a lawyer and partner at Campbell Shatley, in Asheville, N.C., which represents districts primarily in western North Carolina.

Most districts, Mr. Shatley said, have tried to involve teachers and administrators as they draft the criteria by surveying them or otherwise gaining feedback. Some are allowing teachers to “opt out” of the population that will be considered for a four-year contract.

“We’ve had clients say that a majority of their teachers wouldn’t accept a contract,” Mr. Shatley said.

Under a 2013 law, teachers in North Carolina will be moved to a new employment system by 2018-19 that does not include tenure.

SOURCE: Education Week

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg district surveyed teachers and principals and held meetings with them before it settled on the criteria, said Terri Cockerham, the director of human resources for the 142,000-student district, the state’s second largest. Among other things, it plans to select teachers through a point system that assigns more to those teachers who hold national-board certification, who have credentials in hard-to-staff subjects, like math and foreign language, and who hold more than one license.

Board members spoke against the plan before approving it March 25, and they have also passed a resolution requesting a year’s delay in implementing the mandate.

Teachers understand that the board’s hands are tied, Ms. Cockerham added, but that hasn’t stopped them from being frustrated with the new plan.

“They were not in favor of it. Period,” she said.

Lawsuits Filed

Guilford and Durham counties, the state’s third- and eighth-largest districts, respectively, have sued the state to overturn the law. The lawsuit, filed in state Superior Court, says that the requirements interfere with districts’ employment contracts with their teachers and potentially open them up to litigation.

“The 25 percent mandate is so loosely, obscurely, and inconsistently written that the boards and superintendent must necessarily guess at its meaning,” the complaint says. If implemented, “they necessarily will make ad hoc, arbitrary, and/or subjective decisions.”

During a preliminary hearing April 16, a judge requested more information on whether the boards have the standing to sue, the Greensboro News & Record reported.

Separately, the North Carolina Association of Educators has also sued the state, charging that the law’s repeal of tenure violates teachers’ federal and state constitutional rights.

The lawmaker who championed the policies, Senate Majority Leader Phil Berger, a Republican, could not be reached for comment by press time. In a statement his office sent, he said, “We should embrace the opportunity to recognize and reward more of our top-performing teachers who make a lasting impact on the lives of their students, while promoting greater student achievement.” It also referenced a 2013 study on teacher evaluations in the District of Columbia indicating that teachers on the cusp of a pay bonus improved.

Rumors are already circulating, though, that the outpouring of angst occasioned by the law could prod lawmakers into offering fixes when the legislative session resumes in May.

In the midst of the confusion, teachers say they don’t know how much they’ll be making come fall—or even for the multitude of falls after that. After June 30 teachers can no longer earn a 10 percent pay premium for completing a master’s degree, according to the new rules.

Even the $500 annual base-pay increases for teachers selected for a four-year contract aren’t a sure thing, because they rely on the largesse of state appropriators. Only the first year of funding, amounting to some $10 million, has actually been reserved.

Nor is it clear whether some other pay revision will replace the mandate after it concludes in 2018-19.

Retention at Risk?

Anecdotally, observers say, the plan could prove so divisive that it could break down collaboration in schools and affect the state’s ability to keep its teachers.

“A lot of districts are seeing a number of teachers leaving the state to go to another state or leaving the profession altogether,” Ms. Winner said. “And we are also seeing recruitment issues for beginning teachers; we’re seeing fewer students coming out of the university programs.”

Mr. Owens, the Cherokee County teacher, says the fear is real. At a recent meeting of district-level teachers-of-the-year in Raleigh, four of the colleagues at his table were questioning whether to stay in teaching.

And if Mr. Owens is offered one of the four-year contracts, he won’t take it.

“I would just be going against my core beliefs in order to do that,” he said.

Pay and Tenure in North Carolina

Under a 2013 law, teachers in North Carolina will be moved to a new employment system by 2018-19 that does not include tenure.