Although some 90 percent of teachers may be considered “highly qualified’’ under the teacher-quality provisions of the No Child Left Behind Act, varying state definitions of what counts as highly qualified mean that skilled teachers likely remain unevenly distributed among the nation’s classrooms, according to a large-scale federal study released today.

“I think the high compliance rate suggests there were states that set the bar low and, in a way, grandfathered in a lot of teachers,’' said Kerstin Carlson Le Floch, one of the primary authors of the study, which was conducted for the U.S. Department of Education by the Washington-based American Institutes for Research and the RAND Corp. of Santa Monica, Calif.

“To get the real story,” she added, “you have to look below the surface, where we’re still seeing inequities.’'

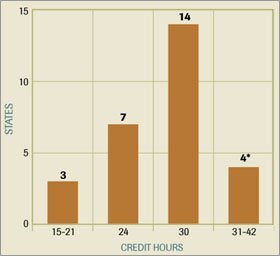

States vary in the amount of subject-matter coursework they consider equivalent to a college major in order for new secondary teachers to meet the content-mastery requirements under the No Child Left Behind Act.

NOTE: These data, from 2004-05, are based on the 27 states and the District of Columbia whose guidelines for highly qualified teacher specified the number of hours equivalent to a major.

* Indicates that the District of Columbia is included.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education

The interim study, part of an ongoing congressionally mandated evaluation of the federal Title I program for disadvantaged students, draws on survey data from the 2004-05 school year for nearly 13,000 teachers, special educators, paraprofessionals, and administrators in 300 districts across the country.

Researchers said the study, which was originally due to be published in 2005, is the largest federal survey to date examining how educators are implementing the teacher-quality provisions of the 5 ½-year-old No Child Left Behind law. Researchers finished collecting data this year for the eventual final report.

Under the federal law, states had until the end of this past school year to ensure that they are staffing core academic and fine arts classes with teachers who hold a bachelor’s degree, are fully certified, and can demonstrate mastery of the subjects they teach through coursework in those subjects, passing tests, or meeting some other criteria.

Among the general education teachers surveyed, the report says, nearly three-quarters said they had met their states’ definitions for being highly qualified. However, 23 percent did not know their status under the law at the time of the survey; another 4 percent said they did not meet the teaching-quality requirements.

The researchers estimated the percentage of highly qualified teachers at 90 percent, though, after examining teachers’ answers to other survey questions and determining that they had met the grade in their states.

Definitions Vary

State policies for determining whether new teachers are highly qualified also varied widely, according to the study, “Teacher Quality Under NCLB: Interim Report.’' For instance, although all but two states had tests of teachers’ knowledge of subject-matter content, the minimum passing scores spanned a wide range. On the Praxis II test in mathematics, for example, the cutoff ranged from 139 of 200 in South Dakota to 163 in Virginia.

By 2004-05, the report also says, 47 states had also adopted an option under the law—known as the High Objective Uniform State Standard of Evaluation, or HOUSSE, provision—that allowed them to set their own criteria for determining whether teachers already on the job met the “highly qualified’’ standard. The standards differed in the degree to which teachers got credit for their years of experience on the job vs. measures aimed more directly at assessing their knowledge and teaching skills.

One result of that state-to-state variation: “Highly qualified’’ often meant something different in schools with high concentrations of poor students than it did in better-off schools, the study found.

In the former group of schools, the report says, “highly qualified’’ teachers tended to have fewer years of teaching experience and were less likely to have degrees in the subjects they taught than so-designated teachers in more affluent schools.

Among other findings, the report says:

• Special education teachers were almost four times more likely not to be considered highly qualified than were general education teachers. The percentage of teachers without “highly qualified’’ status was also particularly high for teachers of non-English-speakers and teachers in middle schools.

• While nearly all teachers took part over the 2004-05 school year in the kind of content-focused professional development in reading and mathematics that the federal law promotes, only a minority of teachers had received extended training in those areas. On a more positive note, teachers in schools with high percentages of poor students and minority students were more likely to receive that kind of training than teachers in other schools.

• About two-thirds of the paraprofessionals surveyed were considered highly qualified under the NCLB law, meaning that they had two years of postsecondary instruction, held an associate’s degree, or had passed a state assessment. Another 28 percent either did not know their status or did not answer that question.