Corrected: The original version of this story contained an incorrect title for David Hawkins, who is with the National Association for College Admission Counseling. His correct title is director of public policy and research.

On a recent afternoon, cousins Samantha Carter and Arielle Giles dropped by the guidance department at Nelson County High School here to show off their acceptance letters to Ferrum College, a small private school in southwestern Virginia.

Sarah Borish, who worked with both students on their applications, gave the cousins her congratulations—and an assignment: Check out Ferrum’s internship opportunities, athletics, and, especially, graduation rates, particularly for students who, like the cousins, are African-Americans.

Ms. Borish, who received her bachelor’s degree in history from the University of Virginia last spring, is one of more than 60 newly minted college graduates serving in the National College Advising Corps. The corps is a network of higher education access programs that places recent college graduates in high schools to address an information barrier that hinders many academically qualified low-income students in gaining access to college.

Ms. Giles, who has lived all her life in this farming community in the Blue Ridge Mountains and will be the first in her family to go to college, credits Ms. Borish with helping her stay on track through the application process.

“If she wasn’t here, I probably wouldn’t have gotten anything done,” Ms. Giles said.

The National College Advising Corps, which started at U.Va., was initially financed in 2004 by a two-year, $623,000 grant from the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, a Landsdowne, Va.-based charity formed with a bequest from the late businessman who was best known as the owner of the Washington Redskins football team. Mr. Cooke died in 1997. The organization focuses on helping academically talented, financially needy students reach their potential.

The University of Virginia, in Charlottesville, which began placing advisers in schools during the 2005-06 academic year, received another grant, for $464,300 for two years that expires this year.

Last year, the Cooke Foundation put an additional $10 million into the program, and expanded it to 10 other colleges nationwide. The institutions will each receive about $1 million over four years, after which they will be expected to take over the financing of their own programs.

The foundation was drawn to U.Va.’s proposal because advisers can do “the high-touch, retail work that we think is essential to encouraging students who otherwise wouldn’t go to college to go to college, and also encourage students who might not go to selective colleges to go to selective colleges,” said Joshua S. Wyner, the executive vice president of the Cooke Foundation.

High school guidance counselors often are overwhelmed with an expansive list of responsibilities in addition to college counseling, including course scheduling, test coordination, career assistance, and discipline. Many counselors can’t spend as much time as they’d like—or as much as some students need—helping their charges with admissions and financial-aid advice.

At many schools, the ratio of students to counselors exceeds the 250-to-1 recommended by the American School Counselors Association, or ASCA, based in Alexandria, Va. Nelson County High, the only high school in the 2,000-student Nelson County school district, has two guidance counselors who each work with a caseload of about 300 students. (A third focuses primarily on test administration.)

The Jack Kent Cooke Foundation gave four-year, $1 million grants to 11 institutions to start the National College Advising Corps. These colleges have advisers placed in schools this year:

• Brown University

• Loyola College in Maryland

• Pennsylvania State University

• Tufts University

• University of California, Berkeley

• University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

• University of Utah

• University of Virginia

These colleges also received grants but are in the planning stages, and will place advisers in schools next academic year:

• Franklin and Marshall College

• University of Alabama

• University of Missouri-Columbia

SOURCE: Jack Kent Cooke Foundation

The problem of high ratios “absolutely has a negative result for college access,” particularly for students who aren’t able to rely on their families for advice in completing applications and seeking financial aid, said David Hawkins, the director of public policy and research for the National Association for College Admission Counseling, or NACAC. The Alexandria, Va.-based group represents high school guidance and college-admissions counselors.

While NACAC, ASCA, and similar organizations advocate hiring more counselors, they say that programs like the National College Advising Corps can help supplement efforts to boost enrollment in higher education.

Tracy F. Miller-Goode, one of the counselors at Nelson County High, echoed that sentiment. “I just think it’s a wonderful program that reaches out to a population that might have been overlooked,” she said. “[Ms. Borish] can give them more concentrated attention than we can, given all our other responsibilities.”

Unlike most high school guidance counselors, the Advising Corps members can focus exclusively on college access. They help students identify which schools to apply to, assist with getting waivers of SAT and ACT entrance-exam fees, and help students and their parents navigate the often-bewildering process of applying for financial aid. They also coach students on the nitty-gritty of admissions applications, such as helping brainstorm over essay topics and revising drafts.

Last fall, Ms. Borish, 22, organized a trip for Nelson County High seniors to Longwood University, a small public college in Farmville, Va. And she is entering students who turn in their Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA, by mid-February in a raffle to win a $100 gift certificate to Wal-Mart for dorm supplies. Ms. Borish also gave presentations to freshmen and sophomores to help get them thinking about their postsecondary options, suggesting they could put themselves on a path toward higher education early in high school by taking challenging courses.

Dustin Saunders, another member of the Advising Corps, who works about 45 minutes away at Charlottesville High School, in the 4,000-student Charlottesville city school district, organized an evening financial-aid seminar for students and their parents. He helped administer and lead an SAT-preparation course. He even showed up on a recent SAT testing day with students’ entry tickets, so they wouldn’t have to worry about anything but the exam.

If preliminary data are any indication, such efforts are paying off, at least in the number of students from the Virginia high schools served by the Advising Corps applying to four-year public colleges in the state, including its top-tier institutions.

During the first year of the program, the University of Virginia saw a 9 percent spike in applications from advisers’ schools. The College of William and Mary, in Williamsburg, and Longwood University received 23 and 26 percent more applications from such schools, respectively.

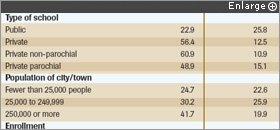

High school guidance counselors spend only about 30 percent of their time on aiding students on postsecondary admissions, according to a 2006 survey by the National Association for College Admissions Counseling.

Counselors in schools with a high proportion of students who qualify for free or reducedpriced lunches spend less time on admissions counseling than their colleagues in schools with more-advantaged populations.

SOURCE: NACAC Counseling Trends Survey, 2006

Most of the 22 advisers from U.Va. work in high schools around the state, serving 23 schools in all. Three advisers are placed in community colleges to aid students in transferring to four-year institutions. This school year and in the past, U.Va. advisers had to commit to one year of service, with an option for a second year. But starting in the 2008-09 school year, the advisers from the university must remain in their placements for two years. Other institutions in the program may choose to keep the second year optional.

Last year, about 35 seniors applied for 20 new slots in the University of Virginia program. Advisers were selected largely on the basis of their commitment to public service and their interest in education, said Keith Roots, the U.Va. program’s director.

The Virginia advisers spend about five weeks over the summer learning what admissions officers look for in successful applications. They’re taught how to prepare students for standardized admissions exams, and how to help families apply for financial aid. They also tour colleges around the state, making connections with the admissions staffs and getting a feel for the campuses.

During the school year, the U.Va. advisers meet back at the Charlottesville campus one day each month for supplemental training. Advisers often suggest topics, which recently included an intensive workshop on the FAFSA. In between those meetings, advisers use an e-mail listserv to swap ideas and offer each other support.

The Virginia advisers receive a stipend of about $20,000 a year, plus a $5,000 grant for each year of service, both of which are financed partly by the federal AmeriCorps program. Advisers can use that money to repay student loans or for graduate study. Advisers’ stipends, benefits, and training are financed by the U.Va. program, not the school districts they serve.

The National College Advising Corps, which is now based at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, isn’t the first program to use college advisers to augment guidance counselors’ college-outreach efforts. It is modeled partly on the efforts of the National College Access Network, which includes more than 250 access programs across the country.

Since the mid-1990s, many of the network’s member organizations have trained their own advisers, often retired teachers and guidance counselors, to serve in a similar capacity in schools and communities. NCAN has partnered with the advising corps program to help provide training and technical support.

In Virginia, the advisers fulfill different roles, depending on the needs of their high schools. Some, like Ms. Borish, work in rural or urban high schools with large populations of first-generation college-going students. They help most of the students in the senior class interested in going to college.

Others, like Mr. Saunders in Charlottesville, focus primarily on specific groups of students who might need extra help with the college-application process.

Charlottesville High School was ranked among the top high schools in the nation by Newsweek magazine in 2007, and serves many children of University of Virginia faculty members. The high school routinely sends many of its graduating seniors to top colleges. But it also has a large population of low-income and first-generation college aspirants, many of them minority-group members or recent immigrants. Most of the school’s six counselors have a caseload of about 300 students each.

Mr. Saunders, 22, generally works with students in the school’s Scholars Program, which helps prepare high-potential students for higher education beginning as early as elementary school. And with the support of the guidance department, he’s also elected to work with seniors whose grade point averages fall between 1.5 and 3.0 on a 4.0 scale. He’s helping about 100 seniors overall, out of a class of 275.

Charlottesville High students say it’s easy to relate to Mr. Saunders, in part because he’s close to their age. LaCorie Steppe, a senior, called Mr. Saunders on his cellphone the Saturday the student received his ACT score. He wasn’t familiar with the exam’s scale and wanted to know how the two-digit number compared with his SAT score.

“I like coming to him more than anything,” said Mr. Steppe, who will be the first in his family to graduate from high school. “He has a gift. … I think of him as my big brother.”

The guide program is still relatively new, and at both Charlottesville High and Nelson County High, it’s taken time for advisers and guidance departments to figure out how best to collaborate. Charlottesville High hosted two other advisers before Mr. Saunders, but those guides’ tenures weren’t as successful, according to Lisa Morales, the chairwoman of the guidance department.

“They were stepping all over our toes,” Ms. Morales said. For instance, she said, one adviser contacted teachers about doing classroom presentations on applying to college, even though the guidance department routinely gives such talks.

And she found the premise of the program “a little insulting.”

“Just having been to college yourself does not give you the credentials” to be a college counselor, Ms. Morales said.

Mr. Roots, the U.Va. program director, said the problems Ms. Morales mentioned have been discussed and clarified at Charlottesville High. “There wasn’t a full sense of communication” at first about the advisers and their mission, he said.

Nicole Hurd, who oversaw the creation of the program at the University of Virginia and is now director of the national program, said that as the program expands, colleges are mindful that they must “get buy-in” from school officials, particularly in the guidance department. Program staff members explain to counselors that the advisers “can only do a sliver of your job. They cannot do [emotional or career] counseling. All they can do is admissions.”

This year, Mr. Saunders joined the guidance counselors in giving the classroom presentations on college admissions, and he used the opportunity to introduce himself and explain his role to students. And unlike his predecessors, he takes part in weekly guidance meetings, at the request of the department, which helps to facilitate communication and student referrals.

Despite her initial skepticism about the program, Ms. Morales said Mr. Saunders “has been a godsend” for many of Charlottesville High School’s students. She added: “I like the fact that colleges are taking more of a role in getting these students to them, and not just leaving it to [K-12 schools].”