With the conclusion of the second round of the federal Race to the Top competition, states across the country—winners and losers alike—are vowing to move forward with ambitious plans to reshape teacher-evaluation systems, fix struggling schools, revamp antiquated data systems, and make other changes aimed at raising student achievement.

Yet predicting the long-term impact of those proposals is difficult. States will attempt to make complicated and controversial policy changes, in some cases with uncertain levels of support from powerful interest groups.

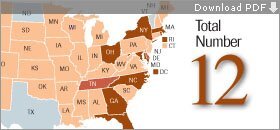

Nine states and the District of Columbia were named winners in the second round of the competition last week, and they will receive a combined $3.4 billion in federal funding. They join the two states, Delaware and Tennessee, that were winners in the first round in March, bringing the total funding for the 12 Race to the Top award recipients to $4 billion. In a parallel competition, another $350 million is expected to be awarded under the program this month to help states design common assessments.

The winners of the $4 billion now face the task of meeting the goals and deadlines spelled out in their applications, which they acknowledge will be challenging.

“Yesterday, everybody’s happy. Today, everybody’s like, ‘Oh my gosh,’” said Robert Campbell, the executive assistant for school reform for the education department in Hawaii, one of the round-two winners. It is slated to receive up to $75 million. Hawaii officials were convinced all along that they had a “bold, ambitious plan,” he added. “Now, it’s showtime.”

Eleven states and the District of Columbia were chosen from among 47 applicants that took part in two rounds of competition for $4 billion in federal economic-stimulus funds.

SOURCES: Education Week, U.S. Department of Education

As was the case in the first round of the competition, the release of the winners’ and losers’ scores drew criticism from officials in losing states and others who described the judges’ methodology as arbitrary and inconsistent. Still, officials in a number of losing states pledged to press ahead with the plans described in their applications.

“Colorado’s disappointed, but undaunted with regard to our reform strategy,” said Richard J. Wenning, that state’s associate education commissioner. His state was considered a favorite by some observers after having approved a law earlier this year that tied teacher evaluations to student performance.

Hard-Fought Competition

The 10 second-round winners, selected from a group of 19 finalists, are: the District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, and Rhode Island. They will receive from $75 million to $700 million through the competition. Delaware and Tennessee received $119 million and $500.5 million, respectively, in the first round. The winners have four years to spend the money to implement their plans.

Over the two rounds, 46 states, plus the District of Columbia, took part in the competition, funded under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, better known as the economic-stimulus program. Only Alaska, North Dakota, Texas, and Vermont abstained.

Obama administration officials have argued that the competition itself will have a broad, positive impact on schools. Thirty-four states have changed laws or policies “to improve education” since the competition began, the U.S. Department of Education said in announcing the second-round awards.

The Race to the Top has “prompted states and districts across America to change laws, remove obstacles to reform, and force stakeholders to work together in ways they haven’t in decades,” Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said last week, in a speech in Little Rock, Ark.

A number of representatives of winning—and losing—states agreed.

Arizona, which lost despite greatly improving its score between rounds one and two, is well poised to pursue aggressively the agenda laid out in its application, said Paul Koehler, the director of the policy center for WestEd, a San Francisco-based research and development organization. He helped the state craft the round-two proposal. Even states that put forward unsuccessful bids helped themselves through the process, he argued.

“If you win, you’ve got a plan, and you’ve got some pretty good funding for that plan,” Mr. Koehler said. He added that Arizona officials reasoned, “If we don’t win, we’ve still got a plan, ... a blueprint to bring stakeholders together. It really got the state motivated.”

The federal Education Department judged states’ applications on a 500-point scale based on more than 30 criteria, which included adopting common academic standards; revamping their data systems; improving teacher and principal effectiveness based on measuring student growth and other factors; turning around low-performing schools; supporting charter schools; and focusing on math and science strategies. States were also encouraged to seek broad support from a diverse set of stakeholders, such as teachers’ unions.

Puzzling Results?

The final scores in round two were criticized by some state officials and advocacy groups, particularly in cases where individual reviewers awarded very different scores to states on the same application criteria, or where states did not seem to receive credit for approving new laws or policies. In addition to their written applications, states sent delegations to Washington to make presentations to panels of judges.

“It’s just incomprehensible to us,” said Colorado Lt. Gov. Barbara O’Brien, whose state missed the cut by ranking 17th.

Ms. O’Brien speculated that reviewers may not have understood the state’s strategy of outlining broad goals for school improvement while leaving implementation details up to local districts.

“It was clear that a couple of reviewers just didn’t understand how you implement [reform] in a local-control state,” said Ms. O’Brien. “You can’t say it’s an objective process, and it certainly hasn’t been normed or standardized,” she added. “I just have no confidence in this process the U.S. Department of Education has put together.”

Another Colorado official, Mr. Wenning, said he was puzzled to see Colorado’s score declined from round one to round two in some categories focused on producing good teachers, particularly one for “developing evaluation systems,” in spite of the state’s passage of its teacher-evaluation law, which drew nationwide attention.

Similarly, Paul G. Pastorek, the state superintendent of education in Louisiana, which ranked 13th and lost out, said he was surprised his state did not fare better in the category judging states on producing “great teachers and leaders,” despite having approved teacher-merit-pay legislation before this round.

“I have to scratch my head and wonder why,” Mr. Pastorek said, “but at the end of the day I know this is the process, and we live [with] it.”

Unlike Colorado and Louisiana, Hawaii did not approve legislation assuring that teachers are evaluated based on student progress. Its application instead says that its education department has a “written agreement” with the Hawaii State Teachers Association to implement an annual performance-based evaluation for teachers and principals, with 50 percent of that evaluation to be based on student achievement. Hawaii will also create a system to achieve a more equitable distribution of effective teachers.

Eight of the 10 winners are located on or near the East Coast, and the only winning state west of the Mississippi River is Hawaii. Yet in a phone session with reporters, Mr. Pastorek scoffed at suggestions that the competition favored any type of state. “These are top-flightproposals,” he said. “This is serious competition.”

Secretary Duncan, in a conference call with reporters after the awards were announced, took pains to praise a number of the losing proposals, including those from Colorado, Louisiana, and California, but said ultimately there wasn’t enough money to pay for them. The administration has proposed spending $1.35 billion in fiscal 2011 to extend the program for a third round.

Although California lost, a number of other heavily populated states were named winners.

They included Florida, which will receive up to $700 million to create tough new expectations for the restructuring of struggling schools. New York, which also was awarded up to $700 million, will expand its “partnership zones” for turnaround schools. They will include clusters of restructured and charter schools using their central district offices for services, but separate scheduling, curriculum, and staffing controls, in exchange for agreeing to make dramatic improvements within two years.

Practical Hurdles

But turning winning ideas into policy will take significant work, several observers said.

Implementing the changes outlined in Race to the Top proposals will not be easy in state education departments that are “compliance-oriented organizations,” with little experience putting in place sweeping, contentious changes in teacher evaluation, school turnarounds, and other areas, said Paul Manna, a scholar who focuses on education governance at the College of William and Mary, in Williamsburg, Va.

Now those agencies will be attempting to focus on “big changes in how schools do their work,” said Mr. Manna, an associate professor of government and public policy. “People are naive if they think that’s going to happen quickly.”

The process of carrying out the winning plans is about to begin in several states. Hawaii, considered a surprise winner by some observers, will use its $75 million award to boost support to struggling, hard-to-staff schools and create incentives for effective teachers to work in them. It also will improve data systems and increase the use of distance technology. Mr. Campbell, of the state’s education department, said one of his biggest concerns is ensuring “fidelity of implementation”—making sure that targeted schools and teachers adhere to the new policies in areas such as formative assessment and teacher professional development.

He compared winning the competition, and implementing the winning plan, to moving to the front of the pack in a bicycle race.

“You break away from the pack,” he said, and once “you’re out front, you see how steep the incline is.”