Relatively small improvements in the skills of a nation’s workforce can have a big effect on its future economic well-being, concludes a new international study that seeks to quantify those benefits.

For the United States, the research suggests, modest gains in student achievement as measured by one international assessment could cumulatively boost the country’s gross domestic product by tens of trillions of dollars over the coming decades.

“There’s almost a one-to-one match between what people know and how well economies have grown over time,” Andreas Schleicher, the head of indicators and analysis for the education directorate at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, said at a briefing held here last week to discuss the findings. “It’s not the quantity of schooling that drives success in countries, it is the quality of [learning] outcomes that we see that is explaining the relationship.”

The Paris-based OECD was planning to release the report this week at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

An increase of 25 points in the average performance of countries on PISA would translate to an estimated economic benefit of $115 trillion in GDP by 2090.

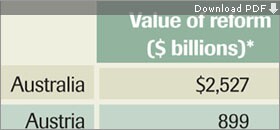

SOURCE: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

The study uses economic modeling to relate cognitive skills—as measured by the Program for International Student Assessment, or PISA, and other international instruments—to economic growth. It relies on nations’ GDP, a basic measure of a country’s overall economic output, for the analysis.

A “modest goal” of having all 30 industrialized countries in the OECD raise their average scores on PISA by 25 points in the next 20 years would provide an aggregate gain of $115 trillion in GDP “over the lifetime of the generation born in 2010,” the report projects. A gain of 25 points, it notes, is less than what was achieved from 2000 to 2006 by Poland, which the report calls the most rapidly improving nation on PISA.

The international average on PISA is 500.

Meanwhile, bringing all nations up to the performance level in mathematics and science of Finland, the OECD member country with the best-performing education system, would result in aggregate gains on the order of $260 trillion in GDP, according to the report.

There is “uncertainty in these projections as there is in all projections,” it cautions, but the authors argue that even reducing the projections considerably suggests very large implications.

“It matters a lot what our students know,” Eric A. Hanushek, an economist at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, and the report’s co-author, said during the Jan. 19 briefing. “It’s not just individual kids, it’s the well-being of our nation in this competitive world.”

Susan K. Sclafani, the director of state services at the National Center on Education and the Economy, in Washington, said the report drives home the need to set higher expectations for U.S. high schoolers. “We’re going to have to talk about establishing a competence level ... that is beyond what we used to think of as sufficient for high school graduates,” she said. “We don’t expect enough of a majority of our kids.”

Lagging on PISA

Mr. Hanushek argues that, based on PISA results, the United States is not doing very well compared with other nations.

In 2006, the United States scored statistically below the OECD averages for in both science and math literacy on PISA, which measures the skills 15-year-olds have acquired and their ability to apply them to real-world contexts. The 2006 reading results of the United States were later invalidated because of printing errors in the test booklets given to American children. (“Printing Errors Invalidate U.S. Reading Scores on PISA,” Nov. 28, 2007.)

The OECD report says the relationship between cognitive skills and economic growth has been demonstrated in a range of studies. The new analysis was based on the PISA in math and science, but not in reading, though it says the math and science scores are “highly correlated with reading-test scores.”

The study walks through the implications of three scenarios of improved student outcomes, the most conservative of which is to lift a nation’s PISA score by 25 points over 20 years. No initial impact would be seen until the higher-achieving students started becoming more significant in the workforce, it says. But as soon as 2042, GDP would be more than 3 percent higher than what would have been expected without improvements in human capital.

While a 3 percent gain might seem small, the analysis points out, it builds up over time. A 3 percent improvement in the GDP in 2042 rises to 5.5 percent in 2050 and 24.3 percent in 2090, according to the report.

“By the end of expected life in 2090 for the person born in 2010,” it says, “GDP per capita would be expected to be about 25 percent above the ‘education as usual’ level.”

The United States, with a current annual GDP of more than $14 trillion, would see growth of nearly $41 trillion in GDP over 80 years, with a 25-point gain achieved within the next 20 years.

In an interview, Mr. Hanushek said that level of increase would make the U.S. results roughly on par with the United Kingdom or Germany.

Under the more ambitious scenario of bringing U.S. scores up to the Finnish level in math and science, which would require an increase of 58 points, the value of its GDP would grow by $103 trillion over the same length of time.

‘You Can’t Copy and Paste’

At the briefing, Mr. Schleicher and Mr. Hanushek discussed some of the potential policy ramifications of the findings.

“You can never translate one system to another, you can’t copy and paste education systems,” Mr. Schleicher said, “but what you can do, what we’re doing here, is you can look at some of the policy levers that emerge from successful education systems and think about how you can situate those kinds of policy levers in a different [system].”

For one, he emphasized that spending more money doesn’t necessarily correlate with improved student outcomes.

“There’s some relationship, but it’s not particularly strong,” he said. “Money is not a predictor of success in systems.”

He added: “When you look at the best-performing systems, what characterizes them is that they get the money to where the challenges are greatest. They get the best teachers into the most challenging schools.”

Mr. Hanushek said “there is nothing more important than a highly effective teacher, but we also know that this is not something that’s easy to change.”

He estimated gains in PISA tied to replacing the most ineffective teachers with “average” ones.

“So if I replace 2 percent of the teachers with an average teacher, I get ... almost 25 PISA points, and if I replace 6 percent of the teachers, I get 50 PISA points, which is the difference between the [PISA results for the] United States and Canada,” he said. “If I can replace 10 percent of the teachers, ... we can beat Finland.”