Ask Billy Harper, the president of Harper Industries, if he has trouble finding employees for his eight construction-related companies scattered across the United States, and he doesn’t mince words. “Absolutely,” he replies.

“It’s the same story, not only in Kentucky, but everywhere,” says the head of the Paducah, Ky.-based enterprise, which has some 1,000 employees. “Just finding warm bodies is hard in itself, people willing to work. And then finding the skills and the traits that you’re looking for makes it even more difficult.”

In a 2005 survey of manufacturers, schools got low marks for students’ work readiness.

SOURCE: 2005 Skills Gap Report. The National Association of Manufacturers, The Manufacturing Institute, and Deloitte Consulting

Figuring out what employers like Mr. Harper want has become an urgent issue as educators try to retool schools to prepare students for both work and college in a rapidly changing economy. And, so far, there are no clear-cut answers.

“I think there’s a lot of ambiguity about what ‘workforce readiness’ means,” said Donna Desrochers, a vice president and the director of education studies at the Committee for Economic Development, a business group based in New York City. “Some people are talking about: When you graduate from college, are you ready for work? Others are asking: If you don’t have any postsecondary education, are you work-ready?

“The general public, when you say ‘work ready,’ probably doesn’t think of any postsecondary education at all,” she said.

Yet even in the construction industry, Mr. Harper said, most jobs now need something beyond a high school education.

“We used to have a construction crew—if they were digging a ditch, you needed three or four laborers with a shovel and a supervisor,” he said. “Now, you’ll have one individual with no supervisor and a backhoe that’s laser-controlled, and he’s got to know how to set that up and how to use it. And that’s an entry-level job.”

But press Mr. Harper a little further about the work-readiness skills he’s looking for, and the list sounds less academic and technical than social—showing up for work on time every day, looking presentable, and being able to communicate with customers.

‘Top Priority’

Plenty of efforts to define work readiness are under way.

Through the American Diploma Project Network, for instance, 22 states are collaborating with Achieve Inc., a Washington-based nonprofit group, to align what employers and colleges expect of students with the knowledge and skills needed to graduate from high school.

Last month, the New York City-based Conference Board and partner organizations sent out a survey to some 10,000 human-resource and training executives asking them what knowledge and skills their companies are looking for in recent job entrants.

And this summer, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and its partners hope to unveil a “workforce-readiness credential” that businesses can use to identify qualified applicants for entry-level jobs.

“Education for the workforce has become one of our top priorities,” said Arthur J. Rothkopf, a senior vice president for the chamber, located in Washington. “It’s an American-competitiveness issue. It’s all about competing and all about having trained people to do the job.”

What’s clear, at least from poll results, is that employers and the general public don’t think that schools are doing enough.

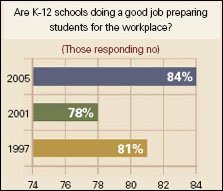

In a 2005 survey commissioned by the Washington-based National Association of Manufacturers, 84 percent of responding members said K-12 schools weren’t doing a good job in preparing students for the workplace. Nearly half indicated their current employees had inadequate basic employability skills, such as attendance, timeliness, and work ethic. Forty-six percent reported inadequate problem-solving skills, and 36 percent pointed to insufficient reading, writing, and communication skills.

Another poll last year sponsored by an influential Washington group, the Business Roundtable, found that 62 percent of the public thought public high schools were not doing a good job “adequately preparing graduates to meet the demands they will face in college and the world of work.”

Manufacturers polled were less happy with students’ work-related skills than with their academic preparation.

*Click image to see the full chart.

SOURCE: 2005 Skills Gap Report. The National Association of Manufacturers, The Manufacturing Institute, and Deloitte Consulting

But Michael J. Handel, an associate professor of sociology at Northeastern University in Boston, noted that while employers complain about the skills of young and high-school-educated workers, “it is unclear whether they are dissatisfied mainly with workers’ cognitive skills or rather with their effort and attitude.”

Manufacturers surveyed foresee a need for workers with strong technical skills who can work in teams.

*Click image to see the full chart.

SOURCE: 2005 Skills Gap Report. The National Association of Manufacturers, The Manufacturing Institute, and Deloitte Consulting

A study released this month by ACT Inc., which produces one of the nation’s two major college-admissions exams, suggests that the reading and mathematics skills needed for success in the workplace are comparable to those needed for success in the first year of college.

The Iowa City, Iowa-based nonprofit organization reached its conclusions based on a comparison of scores on the ACT admissions exam and scores on WorkKeys, an ACT test that measures employability skills. The study looked at scores for more than 476,000 Illinois high school juniors. (“Skills for Work, College Readiness Are Found Comparable,” May 10, 2006.)

The ACT researchers found that the scores needed to do well in first-year college courses were statistically comparable to the scores needed on the WorkKeys test to qualify for a range of occupations that pay enough to support a family of four and offer the potential for career advancement, but that do not require a four-year college degree. Those jobs—such as electrician and construction worker—typically do require some combination of vocational and on-the-job experience or an associate’s degree.

“What do we mean by ready for the workplace?” said Cynthia B. Schmeiser, ACT’s senior vice president of research and development. “What we’re really seeing is it requires comparable skills to readiness for college.”

What Employers Want

The ACT findings echo earlier work conducted by Ms. Desrochers of the Committee for Economic Development and Anthony P. Carnevale, an economist with the Washington-based National Center on Education and the Economy, for the American Diploma Project.

Defining ‘Work Readiness’

For years, experts have been trying to identify what high school graduates need for success in the workplace.

- 1987:

- “Workforce 2000: Work and Workers for the 21st Century,” by the Washington-based Hudson Institute, argues that rapidly increasing demands will create a gap between workers’ skills and those required on the job. By the year 2000, it asserts, “even the least-skilled jobs will require a command of reading, computing, and thinking that was once necessary only for the professions.”

Using data from the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Current Population Surveys, the researchers divided occupations into highly paid professional jobs; well-paid, skilled blue-collar and white-collar jobs; and low-paid, low-skill jobs. They then used data from a federal longitudinal database to look at the course transcripts for 26-year-olds whose occupations fell into those categories.

The upshot, said Ms. Desrochers: “Most young workers who were employed in highly paid professional or well-paid skilled jobs early in their careers had taken at least Algebra 2 while in high school, though about half of young professional workers had taken a higher-level math.” They’d also taken at least four years of grade-level English.

But a forthcoming report by Paul E. Barton, a senior associate at the Princeton, N.J.-based Educational Testing Service, does not support the proposition that those not going to college need to be qualified for college-credit courses in order to enter the workforce.

The report, “High School Reform and Work: Facing Labor Market Realities,” analyzes half of the 20 million job openings projected for 2001 to 2012 by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics in terms of their educational requirements and the quantitative abilities needed to perform each job.

See related story,

It concludes that while a strong case could be made for improving the academic skills of a large proportion of high school graduates, what’s needed is closer to a rigorous 9th grade level of performance. Based on previous studies of what employers say they are looking for when they hire for jobs that do not require a college degree, it finds that employers typically put school achievement below other qualities and attributes—such as attendance, timeliness, and work ethic.

“Academic skills are truly important,” agreed sociologist James E. Rosenbaum, who surveyed plant and office managers who hire entry-level workers, “but they’re not the only thing that’s important. As it turns out, when it comes to what employers want, they do want academic skills, but far more important to them are the work habits and social skills, the ‘soft’ skills.”

Of the 51 employers he interviewed for a study described in his book, Beyond College for All: Career Paths for the Forgotten Half, 35 said that basic academic skills in math and English were needed for the entry-level jobs they were seeking to fill; 13 of those described job tasks requiring math skills, with some requiring algebra and trigonometry. Ten reported tasks requiring reading, writing, and communication skills, with many saying those skills must be above an 8th grade level.

No Help on ‘Soft’ Skills?

Although academic skills aren’t needed for their entry-level jobs, some employers noted, they are needed for their higher-level jobs that entry-level workers can move into.

Mr. Rosenbaum, a professor at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., also found evidence that employers who cited academic-skill needs increased supervisors’ responsibilities and simplified job tasks to match workers with poor skills, and altered job conditions or rules to accommodate more-skilled job applicants or employees.

He worries, though, that by focusing on college goals, not job goals, education policies have been overly concerned with academic deficiencies and not with other weaknesses that employers complain about.

“Policies underestimate how many students are work-bound,” Mr. Rosenbaum said. “They do not help some students develop soft skills, and they do not help many students prepare realistically for their careers.”

“I think there’s a growing recognition and consensus that a higher level of academic knowledge and skills is required for all students for both college and career,” said Gary Hoachlander, the president of ConnectEd, a new California center for college and career preparation, based in Berkeley. “That said, academics is necessary, but it’s not sufficient.”

He argued that there is a substantial body of knowledge and skill that is more oriented to careers and occupations, which requires more systematic attention to students’ problem-solving skills, their diagnostic skills, their ability to interpret and respond appropriately to others, and their understanding of systems.

“I’m not saying that academics don’t pay any attention to those things,” Mr. Hoachlander said. “Of course they do, but not in an explicit, systematic way. And frankly, we don’t assess it, and that’s an issue.”

His concern is being attended to. The ability to solve problems and make decisions and to use and understand systems are two critical entry-level tasks workers need to be able to do, according to a new credential.

Work-Readiness Credential

The Work Readiness Credential is a voluntary national assessment being developed by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce; five states—Florida, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Washington—and the District of Columbia; and JA Worldwide, formerly Junior Achievement, based in Colorado Springs, Colo.

A new credential will assess applicants for entry-level jobs based on the following “equipped for the future” standards.

New workers need to be able to use these EFF skills.

Communication Skills

1. Speak so others can understand

2. Listen actively

3. Read with understanding

4. Observe critically

Interpersonal Skills

1. Cooperate with others

2. Resolve conflict and negotiate

Decisionmaking Skills

1. Use math to solve problems and communicate

2. Solve problems and make decisions

Lifelong-Learning Skills

1. Take responsibility for learning

2. Use information and communications technology*

* This skill is not now tested as part of the credential.

SOURCE: The National Work Readiness Council

“The assessment measures nine skills that employers believe are critical to employment for entry-level jobs” that are not supervisory, not managerial, and not professional, according to Karen R. Elzey, the senior director of the chamber’s Center for Workforce Preparation. Working with technical contractors, the partners brought together groups of employers and sent out surveys to identify the skills needed for entry-level work that cut across industries, she said.

The test will be available in a limited number of states and communities this summer, with a full national release scheduled for next January. It is composed of four computer-based modules: reading, math, speaking and listening, and something called “situational judgment.” For the latter, participants will be presented with real-world scenarios coming from the workplace and asked about the best and worst way to resolve the problem.

The credential was designed to improve the quality of job applicants coming out of state workforce-development systems and to help employers in hiring. However, Ms. Elzey said, “we’ve talked with school systems who are interested in using this for students engaged in internships and work-based learning opportunities, to demonstrate that their students not only possess the necessary academic skills, but also employability and soft skills.”

One of the reasons the states took on the project, she said, is that “there wasn’t a clear definition of what it means to be work-ready.”

To find out what employers think, four national organizations—the Conference Board, Corporate Voices for Working Families, the Partnership for 21st Century Skills, and the Society for Human Resource Management—are working together to conduct an in-depth survey of corporate views on the readiness of new entrants to the U.S. workforce. Those entrants include recently hired graduates from high schools, two-year colleges or technical schools, and four-year colleges.

The survey, sent to some 10,000 human-resource and training executives last month, asks them to rate the knowledge and skill levels of recent job entrants in areas ranging from reading comprehension to creativity; to rate how important each of those skills is to performing successfully; and to predict whether their importance will increase or decrease over the next five years.

“Skills needs are changing so rapidly that we felt it was more realistic to take a five-year outlook on this,” said Jill Casner-Lotto, the project’s research director. “The purpose is for the businesses to clearly articulate their needs to educators, to community groups.”

The project also will include case studies of organizations that are addressing issues of workforce readiness, she said, and panel discussions involving business people, educators, policymakers, and community members.

One structural problem rarely attended to, according to Mr. Barton of the ETS, is that many employers don’t like to hire high school graduates until they are well into their 20s, irrespective of how well they do in high school. Mr. Handel of Northeastern University said that suggests the problem may be one of maturity, not a more general lack of skills.

When it comes to reliable data on workforce competencies and job demands, said Mr. Handel of Northeastern, “there isn’t a lot of hard data on most of these issues.”

The author of a 2005 book, Worker Skills and Job Requirements: Is There a Mismatch?, Mr. Handel just completed a nationally representative survey of wage and salary workers to find out what types of reading, writing, math, problem-solving, technology, and interpersonal skills they actually use on the job.

His goal: to “get some real hard data and numbers on what has really been a very soft debate.”