Semper Gumby.

That’s the catchphrase Sergeant James Reynolds and his Army National Guard unit—part of the 28th Infantry Division—lived by while serving as peacekeepers in Bosnia, back in 2002-03. Semper Fidelis, the borrowed Marine Corps motto, is Latin for “Always Faithful.” Cross it with the iconically flexible green Claymation character, and you have a slogan that helps keep you—and others—out of harm’s way.

Reynolds learned as much early in his deployment, while serving as rear gunner on a Humvee patrolling a Bosnian town. Although the streets were considered safe, the four-man unit, he recalls, was gung-ho—“prepared for anything.” Reynolds was facing backward, watching houses stream past. “All of a sudden, in a break in a wall, a little boy steps out with a gun and points it at me,” he says. “Now, I’m really keyed up because we’re fresh in-country. So I swing over. But because it’s a little kid—he must have been, like, 8—I hesitated.” The gun, it turns out, was a toy.

As the father of a 7-month-old boy, Reynolds doesn’t like to dwell on the incident. Thoughts of what could have happened haunted him for weeks, but it was being Gumby-like—a trait instilled by his then-dozen years of service in the Guard—that spared the child and prevented a lifetime of nightmares.

Flexibility has proved just as important in Reynolds’ current job: teaching 6th grade. Considering that the reservist spends one weekend a month honing his tank-gunner skills, some might feel uneasy about letting him shape the minds of 11- and 12-year-olds. But the second-year teacher is one of about 10,000 former and current military service members who, since 1994, have arrived in the classroom via the federal Troops to Teachers program.

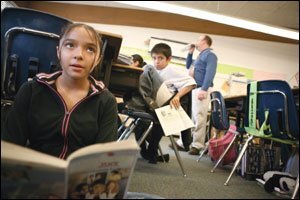

Reynolds, at age 40, doesn’t look like your typical soldier. His red hair is thinning. He’s potbellied. He wears wire-rimmed glasses. And with his next training session three weeks away, he can hang onto his beard for a while. But spend some time with Reynolds at Hybla Valley Elementary—a mostly minority, high-immigrant K-6 school in Alexandria, Virginia—and you can see many of the lessons he’s learned in the Guard coming through.

On this foggy February morning, Reynolds is teaching science, reviewing results from an experiment his students have just completed. Standing in front of a Venn diagram on the whiteboard, marker in hand, he goes over the properties of water, glycerin, and rubbing alcohol.

“If I call your groups ‘cohesive,’ what does that mean?” he asks the mix of African American, Hispanic, Asian, and Pakistani kids.

“Stick together,” a few of them cry.

“Right, you stick together. You work well together.”

“So,” Reynolds says, reviewing the experiment’s second part—tilting wax paper to see how the liquids flow. “Alcohol has a cohesion problem. Once it starts moving, it falls apart. It doesn’t stick to the surface like glycerin. And water had good cohesion, not a lot of adhesion. Roberto?”

“Can I go to the bathroom?”

“Not yet.”

The question—perhaps inspired by all this talk of liquids—distracts Reynolds for a second. Turning to the diagram, he writes “more adhesion” where the circles for water and alcohol overlap. Marisol, a slim girl in a pink hoodie, raises her hand. “Isn’t it the opposite?” she says. “Shouldn’t it be ‘less adhesion’?”

Reynolds looks at the board, then erases what he’s written. “You’re right, these showed less adhesion,” he acknowledges, writing the words. “Thanks, Marisol, for fixing that for me.”

Semper Gumby, indeed.

Hybla Valley’s not the sort of school most teachers pine for. More than 80 percent of the kids receive free or reduced-priced lunches and roughly half are students with limited English proficiency. But it’s exactly the kind of place that Troops to Teachers focuses on. A 2005 study by Old Dominion University’s education school found that 54 percent of the 2,100 Troops teachers it surveyed were employed at schools in which more than half the students were low income.

There’s a reason for that: The program offers participants willing to work in high-needs districts up to $5,000 to cover the costs of earning alternative-route certification. Those who work in the neediest schools and stay on for three years qualify for up to $10,000 in bonuses.

Arlene Inouye, a Los Angeles K-12 speech-and-language specialist and coordinator of the California-based Coalition Against Militarism in Our Schools, calls this “preferential treatment.” “It seems like they’re saying that there’s something special about a military person,” she explains. “My thinking is, What is it about the military that would make them more qualified to be teachers?”

Even if they aren’t more qualified, many teach high-demand subjects such as math, science, and special education. According to a 2005 study by the private National Center for Education Information, TT meets these demands in much higher proportions than the teacher pool as a whole: 27 percent of Troops educators teach math, compared with only 7 percent of teachers overall. There are equally marked disparities in the ratios of TTs to other teachers in the sciences (46 percent to 18 percent) and special ed (44 percent to 19 percent).

Hybla Valley principal James Dallas sees additional benefits in Reynolds. Though he’s still a novice in the classroom, the administrator believes he “really cares for his kids beyond the academic day. And that’s so important for our population.” The school, Dallas says, draws from a community made up largely of transient and working-class immigrant families. According to the NCEI survey, more than a third of Troops educators work in urban schools—twice the proportion of teachers overall. The program also draws more minorities—37 percent versus 15 percent—and a much greater share of men: 82 percent versus 18 percent.

A male teacher, especially at the elementary level, is a role model for students whose fathers are either absent from home or working more than one job to make ends meet, Dallas says. It’s important, he adds, “to have that male figure in front of them, every day, to demonstrate how a male is supposed to do those things that our parents taught us to do—to be respectful, to show respect to women, how we carry ourselves. I think a lot of boys miss out on that because they typically don’t have that male experience.”

Not everyone, however, thinks soldiers make good role models. Inouye, of the Coalition Against Militarism in Our Schools, worries that Troops educators could serve as military recruiters, if only inadvertently. Because he’s their teacher, she says, Reynolds’ sharing of any military experiences “does have an influence on students. And the fact that [TT] is run by the [U.S.] Department of Ed, along with [the U.S. Department of Defense], you can’t separate, a lot of times, that influence.”

Reynolds says when the Guard comes up in class, he doesn’t provide graphic detail or try in any way to recruit. Dallas suggests that Reynolds’ experiences, including stints in Bosnia and Egypt, where his unit helped train Egyptian military forces, bring both personal and academic benefits to students.

“He’s like living history,” Dallas says. “He’s sharing history as it’s occurring. ... I think it’s more about sharing what his experience is all about, and allowing his kids to make up their own minds about what they want to do with their lives.”

The principal also credits some of Reynolds’ flexibility to the sense of teamwork the military fosters. Compared with other new teachers, he says, those with experience in the armed forces are “more open to the whole idea of working together ... because that’s what they’ve been accustomed to—working as a team and valuing every member of the team.”

Dallas isn’t the only administrator impressed with Troops to Teachers. Roughly 90 percent of the principals surveyed in Old Dominion University’s nationwide study said Troops educators were more effective instructors and classroom managers than traditional teachers with comparable experience. About the same proportion of the principals also cited a more positive impact on student achievement.

After the science experiment is finished, 10 minutes remain until the kids have to head off to their special classes. So Reynolds, whose degree is in history, squeezes in a quick lesson on the American Revolution.

Such subject changes are OK with Dallas, who allows his staff some creative room—“as long as we are meeting the objectives that have been pre-established,” says Mary Daniels, leader of the 6th grade team. Reynolds, she recalls, knew early on when to go by the book and when to go beyond: “It was almost like he’d done it before.”

Ellen Colehower, a special ed instructor who was Reynolds’ mentor in 2005-06, also attests to his adaptability. “We spent a lot of time talking about differentiating instruction for kids with special needs, or who aren’t getting it in the traditional way,” she says. “And he was always open to trying new things to meet the needs of students.”

Those needs are many. Because of Hybla’s transient population, its class sizes fluctuate as kids move away and others arrive. Currently, Reynolds has 25 students, seven of whom are special ed, five ESL, and another handful gifted and talented. While Reynolds gets help from specialists like Colehower, he often teaches solo, engaging students by applying lessons to their lives.

Once, when covering colonial America’s taxation without representation, he brought candy and cakes into the classroom, handed each student $100 in fake cash, and told them, “End of day, buy whatever you want.” He then proceeded to “tax” them for visiting the restroom, taking a test, receiving grades, etc. “So, as the day progressed,” he recalls, “they began to get mad at me because they could see what they weren’t going to get.”

This kind of exercise, combined with weekly study of the Sunday Washington Post—donated by the newspaper to each Hybla 6th grader—gives Reynolds the opportunity to link today’s issues, such as immigration, to the country’s constitutional roots. “If I get them to know a little bit about current events,” he explains, “it’s easier to connect it to past events when we’re talking about them.”

As his students gather around, a few of the boys sprawling across the carpet, Reynolds reads briefly from the picture book Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride, by Stephen Krensky. “Dedicated to all Lexington Minutemen, past and present,” he reads. “What’s [the author] mean by that dedication? Do you know what a Minuteman is?”

“Farmers,” one of the boys says.

“Right,” Reynolds replies. “They were farmers and artisans who had their weapons and everything at home. And, supposedly, within a minute, very quickly, if they heard the alarm, they’d be ready to go and defend the town. So they called them Minutemen. So who would be similar to Minutemen today?”

In the discussion that follows, a few students confuse full-timers like police officers and career soldiers with National Guard reservists, who serve the state in which they’re based—during snowstorms or after natural disasters, for example—as well as the country as a whole. The Guard’s logo, in fact, features a Minuteman.

“Guys like me,” Reynolds tells his class. “I have my own job; I’m here every day, doing this job. But then I could be sent to Iraq at any point.”

It wouldn’t be the first time Reynolds had to leave his class. Early in his first year, he was pulled from Hybla and assigned to Egypt for three weeks for a training mission.

For Dallas, it illustrated that flexibility can cut both ways, and the departure made him reconsider his decision to hire a reservist. He made sure, after Reynolds returned, that he got quickly back on track, but until he retires four years from now, the teacher could be called up whenever the Army needs him.

Quotes from second-year educator and Troops to Teachers participant James Reynolds on how he’s handled 6th grade classroom challenges:

Teamwork:

“The military is very much about the team. You’re not an individual; you’re a member of a team. You work with each other, and you look out for each other. And that’s a big thing in school. If you’re a young teacher, and you try to make it on your own, it’s going to be really hard on you because you’re starting from scratch. ... Anything I need, I go to my 6th grade team.”

Admitting Ignorance:

“A lot of people, when they don’t know something—especially young people— they try to hide it. Whereas me, if I have something I’m not good at, I’m just like, ‘I really have no idea what I’m doing with this. Can you help me?’”

Sharing the Passion:

“I went into [teaching] because I wanted to get people interested in history. ... When [my 7th grade teacher] taught history, he taught it as a humanities class. We studied everything about ancient Greece, so we learned all the aspects and really put them together. It wasn’t memorizing anything. And that was fun.”

Discipline:

“Overall, I’m really good to [my students]. So they know when I’m mad. Sometimes you just let a little bit of your anger show, let them know you’re serious. ... [But] certain things you just can’t do in front of the other kids. You can’t embarrass them. So you take them aside, talk to them one-on-one.”

Battling Apathy:

“I’ve had kids tell me, ‘I’m just gonna lay carpet for a living, Mr. Reynolds. It doesn’t matter to me.’ And, sometimes, in a [working-class] area like this, that’s what they think: ‘My parents didn’t finish high school, so I can make it, too.’ I’m like, ‘Go home and talk to you parents about how hard it is. Because you have a PlayStation and ... a house to live in, you think your parents are doing really well. But maybe they’re struggling—both working jobs—to give you all that stuff.’ You see a lot of apathy, and it can be a real struggle sometimes.”

“I try not to think about it often, but in the back of my mind the reality of deployment does exist,” Dallas says. “It would have a profound impact on the children, since they have developed such a positive rapport with Jim and the fact that they are aware of the perils of war.”

Reynolds says that deployment activity is not made known until a month or two before troops have to leave. His guess, based on reports of other units’ activity, is that the 28th Infantry will be deployed in a year or two—perhaps before a school year has begun, perhaps not.

Most classes with Troops teachers don’t have to worry about such interruptions. According to the federal Government Accountability Office, reservists and National Guard members together account for only 20 percent of program participants. But Reynolds admits that statistic might be cold comfort to students he has to leave mid-term.

“I think it’ll be tough on them, yes,” he says. “But I would try to set it up to keep in touch with them [via phone and e-mail] while I was away ... so that there’s some connection.” He adds that he’d also prepare them ahead of time: “I’d definitely talk to them about, ‘You’re a soldier, it’s part of your duty, you gotta do what you gotta do,’ and tell them that I feel maybe I can make [the situation in Iraq] better—do my part to make it what everybody wants. And then I come home.”

Although reading the science fiction book Starship Troopers by Robert Heinlein in 6th grade was what originally sold him on “service to country,” Reynolds says he also dreamed of becoming a teacher, thanks to an engaging history teacher he had at about the same time. But the education profession might have been unattainable had it not been for his military service.

Reynolds entered Glassboro State College (now Rowan College) in New Jersey in 1986. The year after, he joined the Guard, which paid his tuition. But he wanted to make money, like friends who’d skipped college altogether, so he dropped out with just 39 credits on his transcript. Over the next 15 years, he worked a string of dead-end management jobs, running everything from a tuxedo shop to a sulfur mill, and got married and divorced in the process. He now lives with his second wife, Pamela, and their son, Will, in Virginia.

It wasn’t until five years ago that Reynolds, who had lots of free time in Bosnia between patrols, decided to finish his bachelor’s degree. He earned 19 credits through the University of Maryland’s free mix of online and on-base classroom lessons, then finished his B.A. after returning home.

He substitute taught as he began pursuing a master’s in education, but soon came across the Virginia branch of Troops to Teachers, where he heard about the Career Switcher program at Old Dominion University. After an intensive six-week summer course in 2005, he got his temporary K-6 license and by that fall, Reynolds was standing in front of a classroom at Hybla Valley.

To those who’ve spent years earning their education degrees, his teacher-preparation might sound awfully abbreviated. And, although alternate-route programs have proliferated nationwide, experts warn that many of them—including some used by Troops teachers—do not provide key classroom must-haves.

“The basic pedagogical issues about how you structure lessons, how you manage a diverse classroom of 30 kids, how you conduct assessments in ways that will enlighten your teaching—these are not intuitive things,” says Tom Blanford, associate director of new products and programs at the National Education Association. “So if the alternative[-route] programs don’t provide that ... the classroom becomes an experimental field where you learn as you go.”

To some degree, that’s been Reynolds’ experience. He’s much more comfortable in the classroom now than last year—due in large part, he says, to his Old Dominion and Hybla mentors, as well as Hybla’s tight-knit 6th grade team. Age also confers some humility. “I’m willing,” he says, “to come in [to team meetings] and say, ‘Listen, this is something I have no idea what I’m doing.’”

Whatever benefits it brings to the classroom, Troops to Teachers has a checkered financial past and an uncertain future.

The program, created by the U.S. Congress, began turning troops into teachers in 1994, following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. The military, seeking to shrink itself, needed civilian jobs to offer former service members. So it turned to public schools, which were then worried about an impending teacher shortage.

It was initially set up as a two-year program, says Peter Peters, the assistant chief at Troops to Teachers’ national office in Florida. Director John Gantz, who retired in February, was able to spread the money over several years. But by 1999, Peters recalls, “things were looking grim.”

Enter Navy veteran and Senator John McCain, who spearheaded efforts to again fund the program, newly dubbed Troops to Teachers, and transfer oversight from the Defense Department to the Education Department.

Funding has fluctuated in recent years: The program got $29 million in 2003 and about $15 million in each of the following years. And a 2006 report by the Government Accountability Office found that management problems, inconsistent assessments, and reductions in enrollment and funding have kept TT from being all it can be.

Participation has recently decreased, according to the GAO, and while about 10,000 service members or retirees have become teachers in the past dozen years, the report questioned how some of the money was spent: 34 states hired fewer than 50 participants each between 2001 and 2005, but TT placement offices in those states collectively spent nearly a quarter of placement funds.

The GAO also wasn’t pleased with the Department of Education’s coordination between Troops and its other teacher-recruitment initiatives for the military. And although another $15 million is earmarked for it in the Bush administration’s proposed 2008 budget, there’s no guarantee the program will be funded after this year.

There’s also the question of how much of a dent the program is making in teacher-shortage numbers, given the millions of dollars being spent.

Richard Ingersoll, a professor of education and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, has written extensively about teacher recruitment and retention. While he generally favors middle-aged, service-minded people entering the profession, he questions Troops to Teachers’ long-term impact. Compared with the roughly 200,000 educators each year who leave the profession, the addition of 10,000 over a dozen years, he says, is “just a trickle.”

And given the unevenness of alternative certification programs, he wonders whether all Troops teachers are provided adequate training and support. “Recruitment’s fine,” he says, “but if you don’t have retention, then where are you?”

At the moment, Jim Reynolds is convinced he’ll still be a teacher four years from now, when his military obligation ends. Sixth grade is ideal for him, he says, and gives him a chance to hook kids on history before conventional high school curricula drain the life from it. He’s also found Hybla Valley Elementary suited to his experiences.

“I share a lot of my life with [my students]—the choices I made, the mistakes. I don’t hide from them the bad decisions I made, like dropping out of college,” Reynolds says. “And then I put myself back together. It’s important for them to know: It’s OK to make mistakes, and then you move on.”

Last year, while helping an extremely troubled student, Reynolds experienced “that moment you want” as a new teacher: the one that convinces you you’re in the right job. The 6th grader had “a rap sheet longer than most criminals,” according to principal Dallas. At first, Reynolds was at a loss for how to connect with the kid. “But, slowly, in some way, I reached him,” he recalls. “And by the end of the year, that kid went on to honor social studies, 7th grade. He came to me with Walt Whitman poems and was talking about what they meant to him.” Reynolds adds, however, that he doesn’t know exactly what he did.

Dallas does. “Jim was being himself,” he explains. “Sometimes kids get pegged by other students and teachers. And Jim did not allow this student’s previous record to influence how he was going to interact and relate with this student. Jim didn’t let every situation that could have gone wrong go wrong. He was able to step in and intervene and instill a belief in this young fellow that, ‘Hey, you’re a smart kid. You have a lot going for yourself. Recognize your potential, recognize your talent. And work to that potential.’”

By the end of that year, during which he wasn’t sent to the principal’s office even once, “he became a 6th grade leader,” Dallas says. “So [Reynolds] was someone who really believed in [the student’s] ability, who believed in his capacity. I think that made a significant difference in the outcome.”

Rich Shea is Teacher Magazine ‘s editor-at-large.