Cassandra Barnett has had a hand in selecting thousands of books for the shelves of school libraries in this community, a task she has honed almost to an art form over nearly three decades as a librarian here.

In the light-filled library at Fayetteville High School, where she has worked the past six years, Ms. Barnett has spent hundreds of hours perusing book publishers’ catalogs and professional journals, analyzing multiple abstracts and reviews, and even reading many of the books herself. Her constant aim is to develop a collection that will intrigue, inform, challenge, and entertain the nearly 2,000 students who use the facility.

But last year, when a student’s mother pushed for officials in the 8,700-student Fayetteville school district to remove dozens of books from the stacks for content the parent deemed too sexually explicit or mature for teenagers—content she highlighted using graphic excerpts on her personal Web site—Ms. Barnett and her library colleagues were forced to re-examine their decisions and the entire book-selection process.

“I started questioning just how good a job I had been doing in selecting those books,” Ms. Barnett said this month.

The soft-spoken woman was among the school librarians caricatured in the editorial cartoons of local newspapers and dubbed “pushers of porn” by some critics. There was even a request to state law-enforcement officials to have the librarian and some district administrators charged with crimes under a state law prohibiting the distribution of pornography to minors.

“We try very hard,” Ms. Barnett added, “to make sure we’re putting the right books in the right kids’ hands.”

The American Library Association has tracked challenges to books at public and school libraries since 1982. The ALA’s 10 most challenged books of 2005 reflect a range of themes. The books, and objections to them, are:

| • It’s Perfectly Normal by Robie H. Harris, for homosexuality, nudity, sex education, religious viewpoint, discussion of abortion, and unsuitability for age group. | |

| • Forever by Judy Blume, for sexual content and offensive language. |

|

| • The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger, for sexual content, offensive language, and unsuitability for age group. |

|

| • The Chocolate War by Robert Cormier, for sexual content and offensive language. | |

| • Whale Talk by Chris Crutcher, for racism and offensive language. |

|

| • Detour for Emmy by Marilyn Reynolds, for sexual content. | |

| • What My Mother Doesn’t Know by Sonya Sones, for sexual content and unsuitability for age group. |

|

| • Captain Underpants series by Dav Pilkey, for anti-family content, unsuitability for age group, and violence. |

|

| • Crazy Lady! by Jane Leslie Conly, for offensive language. |

|

| • It’s So Amazing! A Book About Eggs, Sperm, Birth, Babies, and Families by Robie H. Harris, for sex education and sexual content. Off the list this year, but on for several years past, are the | |

Off the list this year, but on for several years past, are:

| • The Alice series of books by Phyllis Reynolds Naylor | |

| • Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck |

|

| • Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain. |

|

Other books that have appeared on the list at least once:

| • The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank |

|

| • Are You There God? It’s Me Margaret by Judy Blume |

|

| • Julie of the Wolves by Jean Craighead George. |

|

| • The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury. |

|

SOURCE: American Library Association

The work of librarians can be a lifeline to youths dealing with difficult personal issues, such as family strife, growing up, and sexuality, Ms. Barnett believes. Their selections became a lightning rod, however, when Laurie Taylor, a Fayetteville mother of two girls, then ages 12 and 13, campaigned to restrict middle school students’ access to a handful of library books. Her efforts, which began in the spring of 2005, evolved into an impassioned fight against some 50 titles at both the middle and high schools, subjecting the district to the wrath of conservative pundits and advocacy groups.

In the end, this past spring, Fayetteville district officials rejected the intense pressure, and access to the books in question was left unrestricted. But in the midst of intense media coverage and a counter-campaign by parents and students who pushed for open access to the materials, district officials concluded that their own procedures for handling book challenges were flawed. In the months since the storm abated, district administrators and library media specialists have crafted sounder, more structured guidelines for addressing parents’ concerns over library collections and instructional materials.

“There is a gulf of opinion in this community about what is and isn’t appropriate material,” said Fayetteville Superintendent Bobby New, who was also under pressure from leaders at his church and his own parents to remove the materials. Ultimately, Mr. New said, it is the job of all parents to scrutinize what their children read.

“We decided it’s in the library because it has some curricular value,” he said, regarding the challenged books. “Perhaps there is some offensive language, but we don’t deem it necessary to remove it.”

Fayetteville is far from the first school district to be caught off guard in the face of a challenge to books and instructional materials. Several of the books that created a furor in this college town of some 60,000 have been the subject of controversy, and censorship attempts, elsewhere for years.

It’s Perfectly Normal by Robie H. Harris, a sex education guide for middle school students featuring cartoon-like illustrations, topped the list of books challenged in this district, and it was also the most controversial title nationwide in 2005, according to the American Library Association.

The Chicago-based professional organization, which is observing Banned Books Week this week, has documented book challenges—defined as any formal, written complaints about a book—in public and school libraries for the past 25 years. About 70 percent of such complaints occur at school libraries.

The Harris volume, which has been a perennial on the ALA’s list, is most often criticized for its portrayal of subjects such as masturbation and homosexuality as “perfectly normal.”

Most of the complaints nationally have focused on content the challengers said was sexually inappropriate, contained offensive language, or was violent, racist, or anti-family. Books by Judy Blume, J.K. Rowling, R.L. Stine, and other authors popular among young people also appear regularly on the list, as do classics such as John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, and J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye.

Reports of formal challenges to school library books dropped last year to 405, down from nearly 550 in 2004 and a high of nearly 650 in 2000, a trend the ALA attributes in part to better professional development for librarians.

“We have been rather successful in preparing librarians to cope, with better policies … and support,” said Judith F. Krug, the director of the ALA’s office of intellectual freedom since it was founded in 1967. “Very often, the librarians handle these issues on their own, and we don’t even know about them.”

When challenges have gone beyond the schoolhouse, the courts have generally come down on the side of intellectual freedom.

The U.S. Supreme Court has squarely addressed one case involving a challenge to school library books, although the outcome was untidy. In Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico in 1982, the court decided 5-4 that a school board’s decision to remove school library books that had been challenged by some in the community was subject to court scrutiny under the First Amendment. There was no agreement among the majority on an opinion, however. In a plurality opinion for three justices in the majority, Justice William J. Brennan Jr. observed that the school library is a place for a student “to test or expand upon ideas presented to him, in or out of the classroom.”

The clash here in Fayetteville—home to the University of Arkansas and a liberal enclave in a generally conservative Southern state—took school leaders somewhat by surprise. It highlighted the need for sound school- and district-level policies for dealing with concerns and criticisms raised by parents over content in school libraries and classrooms, some experts say

“There are way too many cases where either there was a policy in place that was a bad policy, a policy that wasn’t being followed, or no policy” for dealing with complaints about books or instructional materials, said Millie Davis, who compiles an annual report on censorship in classrooms for the National Council of Teachers of English, based in Urbana, Ill.

In the episode here, the lack of a clearly defined process and timelines for answering such challenges may have aggravated the situation, administrators say.

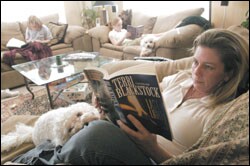

Laurie Taylor, the mother who complained, is no book-burner. Books, in fact, have been a cherished part of the daily routine for the former U.S. Navy diver and her two teenage daughters, Hannah and Emmy Cummings. But when Emmy, who is now 14, described in explicit detail some of the lessons from her sex education class at McNair Middle School last year, Ms. Taylor feared the content was too mature for her 7th grader. Then, a class trip to the local production of a play with adult themes heightened the mother’s concerns about what was being taught at Emmy’s school.

It was then that Ms. Taylor began scrutinizing curriculum and materials offered at the school, and used the online library catalog to review its book collection. When Ms. Taylor learned of Ms. Harris’ It’s Perfectly Normal, she thought she was doing the librarian a favor by pointing out what she considered its racy content, including illustrations of a couple having intercourse, and a teenager masturbating.

“I thought they’d say, ‘Oh my gosh, you’re kidding,’ and remove the books, and that would be the end of it,” said Ms. Taylor, a 40-year-old who coaches softball and teaches Sunday school.

That discussion with the librarian was only the beginning. When school officials dismissed her concerns, and could not offer her a practical way of restricting her children’s access to a whole genre of books with themes she objected to, Ms. Taylor got angry.

“A prude I am not,” she said. “But if any of these books were made into a movie, they would be rated R, and a 13-year-old would be prohibited from seeing it” without a parent or guardian.

Ms. Taylor went to the news media with copies of what she considered lewd passages and sexually explicit content in the long list of books she reviewed. When Ms. Taylor believed Mr. New had dismissed her complaints, she bypassed the district administration and took her demands to the school board. Under the district’s policy on book challenges, a review committee examined the three books she formally challenged: It’s Perfectly Normal; It’s So Amazing, also by Robie Harris; and The Teenage Guy’s Survival Guide, by Jeremy Daldry. But at the end of the 2004-05 school year, the school board discarded the committee’s recommendation that the books be kept on the shelves. The board ordered that the books be placed on a restricted shelf.

That move irked the librarians and the parent group and students who spoke out against what they saw as censorship. But it empowered Ms. Taylor, who began making lists of other books with content she considered questionable and forwarding them to the district. However, she was only permitted to challenge one book at a time. She ended up dropping the complaint about her expanded list.

Ms. Taylor said that she never sought to have books removed from school libraries. After finding dozens of books she considered potentially harmful to her daughters, and with no practical way of restricting their access to all of them, she wanted the books to be identified in some way to warn students of their mature content or to restrict their use.

“I don’t care what anyone else’s kids read,” she said. “But I think this was a no-brainer. … I think I should be able to say my kid can’t check this out.”

Once Ms. Taylor’s efforts grew to encompass more and more books, and threatened the choices of other students, opposing groups became more vocal.

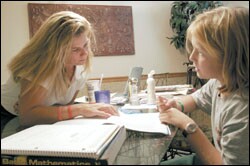

As a family doctor in Fayetteville, and an instructor of youth sex education classes at her church, Janet Titus was opposed to the school board’s restrictions. After reading the Harris books, and asking her 6th grade son to do the same, Dr. Titus thought those titles, as well as others she read, could help youngsters sort out complex and confusing facts about their own development.

“I thought the books were perfectly appropriate for that age range and covered a lot of the material they need to know,” said Dr. Titus, who helped rally other parents to speak out at a special meeting of the school board in September of 2005.

Eryn Haley-Brothers, who graduated from Fayetteville High last year, got a firsthand lesson in civic action when she organized students to oppose any restrictions on library books.

“The scary thing was that not many teenagers knew what was going on,” said the 18-year-old, who had read more than half the books on Ms. Taylor’s list. Push, by Sapphire, a novel available in the school library about a young girl who suffers through poverty and incest, “was the saddest book I ever read,” Ms. Haley-Brothers said. “I could understand why someone with a conservative eye would want to ban it, but if you really look at the core of the book, it’s about poverty in America and how it affects everyone.”

After months of work and 15 drafts, the district this past June came up with a new policy that defines a step-by-step process for parents to follow to challenge library materials. Parents must first read the entire book, discuss it with a teacher or librarian, and outline their concerns in a written “request for reconsideration.”

If the principal cannot resolve the parent’s concerns, the complaint works its way through the district administration, and could eventually be turned over to a review committee selected by the superintendent. District officials have worked to train librarians and school principals to handle initial discussions with parents before the complaint proceeds up the district hierarchy.

Read related story,

“We want to make sure the parent understands there is a process that’s fairly well defined,” Mr. New added. “We’ll be able to meet the criticism earlier, and hopefully address it at the building level.”

The district has also introduced a formal preview period for books purchased for school libraries, allowing parents to see the titles before they go into circulation.

While it is a clear guideline for educators here, the lock-step policy is also intended to allow a dispassionate review of complaints and minimize the emotion that tends to fuel such disputes, Superintendent New said.

Ms. Barnett, the librarian at Fayetteville High, hopes the new policy can shield her and her colleagues from the kinds of personal attacks they encountered.

“The hard part to take was not so much that people disagreed with the selections we had made,” she said. “There was a certain element that questioned the intent and integrity of what we did and why we made the selections.”

The storm seems to have calmed. Just one parent, for example, has visited the Fayetteville High library to look at the books there since the policy went into effect over the summer.

For her part, Ms. Taylor was not satisfied with the outcome. She has enrolled her daughters in a private Christian school and is contemplating a lawsuit over the issue. She is somewhat appeased, though, that the district is looking more closely at its book selections.

“People come up and ask me how it feels to be a loser,” Ms. Taylor said. “I’m not a loser. I achieved exactly what I set out to do: inform parents about the material their kids are exposed to.”