Includes updates and/or revisions.

After tangling in litigation for close to a decade, the District of Columbia school system agreed in 2006 to work quickly to pare down a backlog of cases related to special education services it had failed to provide to students with disabilities.

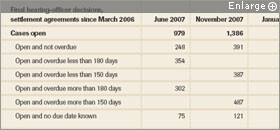

Two years after the decision in the class action, the backlog of cases is still large, and growing. School district officials acknowledge they’ve missed most of the deadlines imposed in the Blackman-Jones consent decree, named for the plaintiffs in two cases that were ultimately merged.

But school officials and lawyers representing the plaintiffs have decided to put aside further legal action for now. Both sides say that despite delays and false starts, they have real hope they can create lasting changes for the 50,000-student district by working together instead.

Much of the change has been spurred by the arrival of Michelle A. Rhee, the new schools chancellor. The work hasn’t always been pleasant, people involved say. In conversations described by one school official as “gut-wrenching,” district leaders have agreed that the special education system has been broken for years.

“What’s happening is quite exciting,” said Ira A. Burnim, the legal director of the Judge David L. Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, in Washington, and one of the lawyers for the plaintiffs in the Blackman-Jones case. “It’s an effort to more sensibly address the huge volume of complaints and unimplemented hearing-officer decisions.”

An Alternative

The “alternative dispute resolution,” reached last December, does not carry the same legal weight as the consent decree, but it outlines broader goals that the school district has committed to carrying out.

Together, the parties have come up with plans to strengthen the district’s fragmented case-management system by using 30 case managers to provide intensive services to 500 students.

Among other changes: By the start of the 2008-09 school year, eight elementary schools and eight middle schools will be designated “exemplary” schools providing full-service, inclusionary education for students with disabilities.

The district also plans to create open seats for students with disabilities at well-regarded schools by paying those schools a stipend, above and beyond the standard per-pupil allocation, based on how many students they accept. Principals will be free to use that money for other services within their buildings.

The District of Columbia public school system has been trying to close special education cases, but is making little progress. Under a new agreement, the district is working on the backlog while trying to make broader changes to improve its special education system.

SOURCE: April 7, 2008, status report on Blackman-Jones case

While due-process hearings are rare in some school systems, they have become the norm in the District of Columbia. Negotiations between the school system and the lawyers led to the creation of a team of five school officials that pores over each request for a due-process hearing. Those come in at a rate of a dozen or so per day. The officials are authorized to break down barriers and offer settlements to parents on the spot.

“To me, it is a hell of a good approach to systemic, deep-seated problems,” said Peter J. Nickles, the interim attorney general for the District of Columbia and a close adviser to Mayor Adrian M. Fenty, who appointed Ms. Rhee. “Why spend your time in court, where you’re losing sight of the kids?”

At the same time, Mr. Nickles said, the school system has a vested interest in trying to keep the other side happy. If the Blackman-Jones lawyers chose to argue that the district was in contempt of the consent decree, the school system would lose, he said. It could then face fines, or the system could be placed in court receivership.

“We have to ensure that we don’t try the patience of the plaintiffs,” Mr. Nickles said. “At the same time, we have a school system to run.”

Mr. Burnim sees his job as nudging—and sometimes pushing—the district in a direction he believes can help the most students. As he puts it: “You can’t do any worse than you’re doing now. So why don’t you take some risks?”

Private Placements

Private placements for students with disabilities, some costing tens of thousands of dollars a year, are also under review. For fiscal 2007, the school system paid $118 million in tuition for out-of-district placements, out of a total budget of about $1 billion.

One achievement that district officials note is finding alternative placements for eight of the 12 Washington students enrolled in the Judge Rotenberg Center in Canton, Mass., which uses “aversive skin-shock treatment for severely disturbed students,” according to information from the school. Placements at the center cost the system $250,000 per student, per year.

Tameria Lewis, the interim assistant superintendent for special education in the District of Columbia Office of the State Superintendent, the equivalent of a state education agency for the nation’s capital, said she participated personally in each of the individualized-education-program hearings for the students enrolled in the Rotenberg center. Even contentious meetings can end in hugs, she said.

“I am amazed at the capacity of families to want to believe,” Ms. Lewis said. “And these families know other families. The key to this is families; we cannot do this if we cannot bring the families along.”

But whether parents ultimately will start trusting the school system again, after years of intractable problems, is an open question.

Rochanda Hiligh-Thomas, the senior staff lawyer for Advocates for Justice and Education Inc., a local parents’ group, said changes at the central-office level still have to flow down to schools.

“There’s a lot of distrust there,” she said, referring to parents. “School systems provide a service. Customer service is key. I think that’s lost, a lot of times.”

And the work relies not only on the goodwill of the lawyers and the district officials, but on U.S. District Judge Paul L. Friedman, who issued the consent decree. He has allowed the parties some latitude, but has the right to hold the school system in contempt if it continues to fail to meet the deadlines imposed in the decree.

Richard J. Nyankori, the special assistant to the chancellor, is part of the team that reads through the complaints. Though he would like to see the backlog reduced, he believes that many of the cases are paperwork problems. Creating a robust system of special education will eventually slow the number of complaints, he believes.

“Clearing the backlog is not the same as educational reform,” said Mr. Nyankori. “The core of the problem is creating a stronger general education system.”