For years, the rooms now occupied by the engineering academy at Soddy-Daisy High School in southeastern Tennessee reverberated with the music of an award-winning marching band. But the band recently moved into a new state-of-the-art facility, and the trademark sound that now emanates from the old practice rooms is a rat-a-tat-tat of a different kind. It’s the persistent clicking of computer mice.

Guided by the hands of the academy’s nearly 120 students, the mice follow the drumbeat of Eric Thomas and his brother Mark. Four years apart in age, the siblings teach side by side in adjacent rooms, where computer screens are by far the most predominant feature. There are 24 in each, and they line three of the four walls, which are otherwise devoid of the posters, pictures, and inspirational sayings that usually constitute school décor. Each classroom also has a projection screen and a well-worn light switch.

A lumbering 40-year-old with a low-key demeanor, Eric typically conducts his class from behind the computer at his desk. The projector casts an image of his screen on the wall, and on any given day it might feature a Hummer, a bicycle frame, or the architectural rendition of a house. Eric calls the images “isometrics,” and he shows students how to recreate them on their own computers using a high-tech piece of design software called Autodesk Inventor.

“We’re going to sketch in doors, windows, and closets,” he says one January morning, “and then we’re going to extrude it.” The word “extrude” comes up frequently in Eric’s class. It refers to a computer command that converts a stick figure into a three-dimensional image and, if you want to get fancy, another command that makes it spin and twirl across the screen.

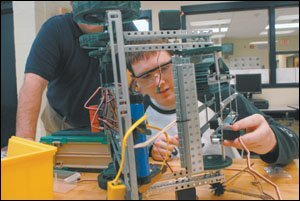

Mark, at age 36, is also a large man, and the students in his class tend to be less sedentary than Eric’s. When they’re not at their computers, they usually hover over bits and pieces of soldered wiring that look like the insides of a radio or a telephone. Their teacher moves at a faster pace than his older brother; he’s more inclined to dart from one computer, or huddled student, to the next. But like Eric, he follows through until each kid has figured out how to calculate the voltage, the current, or the resistance needed for an electrical project—until the proverbial lightbulb goes on.

After years of foundering, the same could be said for vocational education, which started losing ground to the push for more rigorous academic standards in the early 1980s, followed by the onset of testing and accountability. Over the past several years, improved vocational programs have emerged, with a renewed focus on academics. “Vocational education is trying to come back and establish its significance in a modern technological world,” says Robert Balfanz, a researcher at Johns Hopkins University.

Nowhere is that comeback more noticeable than in the Chattanooga area, where the sprawling Hamilton County district began launching academies—independent, career- focused schools within schools—four years ago. Soddy-Daisy’s engineering academy combines three prevailing trends in high school reform: small-school settings, high academic standards, and a broader, high-tech definition of vocational education that has little to do with the home ec and auto shop classes of yore.

While district officials say it’s too soon to gauge the success of the overhaul, they point to early signs of progress in the form of improved attendance and decreased dropout rates. The district’s showcase example, a construction academy at East Ridge High School, frequently hosts educators from across the country.

The goal is to make vocational ed an option for all students, in part by ridding it of its stigma as a dumping ground and making it an effective means of preparing kids not only for the work force, but also a college career. But finding teachers who can bridge the vocational and academic worlds is no easy task, and like the Thomas bothers, they often come from unexpected backgrounds.

The town of Soddy-Daisy is located in the distant shadows of Lookout Mountain, about 20 miles north of downtown Chattanooga. The once-separate hamlets initially thrived on coal mining, but now the region is known for a different kind of fuel. In 1969, the same year that Soddy and Daisy consolidated into one municipality, the Tennessee Valley Authority started building the Sequoyah Nuclear Plant, the city’s most notable landmark. Otherwise, Soddy-Daisy is a growing bedroom community, where small-town charm is gradually losing ground to suburban sprawl. Subdivisions are sprouting up on once-remote hillsides, and signs of modernity—a Wal-Mart Supercenter, a Wendy’s, and a Zaxby’s restaurant—have opened at a steady clip.

But the city and the school are still far removed from the upheaval that took place nearly a decade ago, when elected officials voted to merge Chattanooga and Hamilton County’s districts—“one urban and high poverty, the other suburban and middle class,” says superintendent Jesse Register. He was hired to oversee the controversial merger, which brought together largely separate African American and white student populations. Following the creation of magnet programs to speed desegregation and a single-path diploma that eliminated academic tracking, the district settled on a $22 million effort centered on the career academies. The funding includes $8 million in grants from the Carnegie Corporation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, some federal money, and $6 million from a local education foundation.

The district’s approach incorporates required coursework—reading, writing, and arithmetic—into vocationally focused academies. The small-school setting helps foster a sense of belonging for students, says associate superintendent for secondary education Sheila Young. The academies, which range in focus from construction and engineering to the liberal arts, provide academic rigor as well as a range of career options. They’re also tied to the business community, Young adds, and represent the entire student body, not just a particular race, ethnicity, or grade-point average.

Over the past four years, 27 academies have sprouted at 14 of the district’s 17 high schools, and a few campuses now have wall-to-wall academies. Each school is left to determine the kinds of academies it wants, how many, and how quickly it wants to create them. That approach is key because developing the programs is a long-term project, according to Balfanz. “The school has to really stick with it and be committed, and over time some really good stuff can happen,” he says.

At Soddy-Daisy, the pace has been slow and deliberate—the school is one of the most affluent and homogeneous in the district, overall test scores are high, and it does a good job of getting kids into college. But it had a troubling dropout rate—nearly 30 percent in 2001, says principal Robert Smith—and that was one of the reasons he decided to take the plunge two years ago. His school opted for a 9th grade academy and an engineering academy, and that’s when his plans converged with those of the Thomas brothers, who at the time were beginning their second careers at nearby Hixson High School.

Located closer to Chattanooga, in the city’s northern outskirts, Hixson happens to be where the Thomas boys grew up. As youngsters, “we played ball—baseball, basketball,” Eric recalls. They also played football, rode bikes, and fished in a branch of the Tennessee River that runs close to the four-bedroom ranch house where they lived with their parents, another brother, and a sister.

Eric, the oldest, and Mark, who’s third in line, never intended to become teachers, much less ones who work under the same roof. Mark wanted to be an anesthesiologist, while Eric studied psychology and sociology. But Mark wound up working as an auto mechanic for several years, later becoming a project leader at a manufacturing company. Eric would go on to work at a signmaking company in Georgia, where he developed an expertise in computer-assisted design. After nearly a decade there, he heard about an open vocational ed position at Hixson. He began teaching drafting, and eventually talked Mark into the school’s auto-mechanics classroom.

Then Eric stumbled upon Project Lead the Way, a pre- engineering program now in place at 1,300 schools nationwide. One of its trademarks is intensive teacher training, and the brothers spent two weeks at the University of South Carolina, where they attended class for eight hours a day, followed by four hours of homework each night. “They call it boot camp,” Eric says. “It’s pretty involved,” he adds, by way of understatement.

By then, the brothers had met Smith, who has been running Soddy-Daisy High for 16 years. Smith got his diploma from the school he now leads in 1967, two years before the TVA broke ground on the nearby nuclear plant—one of the main reasons he and his fellow administrators wanted the first career academy on campus to have an engineering theme. While access to the plant has largely been restricted since the September 11 attacks, the facility still exerts a huge influence over the school, says Joel Laney, a former English teacher who now runs the academy. “A lot of parents work at Sequoyah,” he says, “and if someone in your family doesn’t work there, you know people who do.” The TVA also runs three nearby dams and has a large administrative facility in downtown Chattanooga.

If the Thomas brothers are the drum majors of the school’s engineering academy, Laney, who’s preparing to launch two new academies—one with a business and mass media focus, the other geared toward liberal arts—is the band director. This particular ensemble also includes teachers Vic Candler (physics), Donna Campbell (English), Jim Parker (algebra 2), Richie Wood (biology), Wendy Evett (special education), and lead counselor Ellen Chamberlain, all of whom integrate the academy’s work into their academic subjects.

Campbell’s class, for instance, is “still English,” Laney says, “but over a week’s time you can detect a little slant, a little tilt toward engineering.” Her writing assignments often have an engineering angle, and Campbell places extra emphasis on literary engineers such as Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson.

And Candler teaches an applied physics class that’s more hands-on and less theoretical than his AP courses. Academy students build bridges, shoot off rockets, and crash-land toy cars from great heights. More important, he now teaches six physics classes a year, the most ever at the school, and for the first time they include special ed students. Candler likes to call the result “physics mania at Soddy-Daisy.”

While a cross section of Soddy-Daisy students have opted to attend the engineering academy, one common denominator is that many like to “build stuff.” Often, that means taking things apart and putting them back together. Junior Aaron Howard, for example, eagerly recalls disassembling his home computer. “I messed it up,” he says, “so I had to get a new one.” Undaunted, he took apart his Xbox gaming system. That, he says, “I got back together.” While at school, he’s most impressed with the capabilities of the Inventor software he gets to work with in Eric Thomas’ class—what classmate Andrew Fusco calls the “eye candy of the digital world.”

Located near the end of an L-shaped corridor, the academy lacks flashy decor or other bits of pedagogical eye candy. But it attracts honor roll students, caters to those with special needs, and, in many cases, taps into the latent talents of lackluster students. “We’re not choosy about who comes in,” Laney says. “We will take a C, D student, and turn [him or her] into an A, B student.”

Such was the case with Steve Keylon, a senior who began taking engineering courses his junior year. Previously, the computer-savvy teen had taught himself how to create Web sites and write software, but with the exception of math, he typically did poorly in class. “I’d get a report card,” he recalls, “and be happy to see Ds.” Now he’s making As and Bs in all his classes, and he attributes the turnaround to the academy. “It took 10 years,” he said, “but I figured out school is important.”

Turnarounds like this one are starting to add up. The state report card for Hamilton County schools already reflects some improvements—particularly in English, where last year’s 9th graders logged an 87 percent pass rate, up from 82 percent in 2003. In 2005, districtwide attendance exceeded 91 percent, and at Soddy-Daisy, the dropout rate fell to a mere 12 percent—down from 30 percent in 2001.

Soddy-Daisy’s engineering students, in particular, tend to have clear-cut career goals as well as a keen interest in higher education. Like many in the academy, Steve now plans to study for two years at the local community college, Chattanooga State, and then transfer to the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga. “I’d love to be a software engineer,” he says.

The Thomas brothers believe that the academy prepares kids for the rigors of both engineering and more common post-secondary subjects. “A lot of times you will get into college, get into engineering, and drop out,” Eric says. In fact, the attrition rate for engineering students nationwide exceeds 50 percent. In many cases, talented vocational students not exposed enough to basic academics in high school “couldn’t make it through the first semester,” Mark adds.

But as their students continue clicking away in the former band rooms, the teachers agree that it’s the practical application of core subject material to the vocational arts that gets them through high school in the first place. “When they come into our class, they’ll say, ‘Wow, I do need to know that,’ ” Eric says. “And that, the flickering on of the proverbial lightbulb, is pretty neat.”