Earning a high school diploma is one of the milestones for students who come to the United States from other countries. But for those who arrive in their middle to late teens, learning enough English to earn a diploma can seem all but impossible.

Some students from Mexico and elsewhere in Latin America, however, are discovering an option that has received little public attention, even among educators: the Spanish-language version of the General Educational Development test.

The GED certificate, which is recognized by all states as the equivalent of a high school diploma, can be earned by taking the GED test in Spanish or French, as well as English.

As debate over immigration simmers in Congress and among the public, the foreign-language GED could get more scrutiny. Though the debate has centered on border security and the status of illegal immigrants, the issue of language—especially as it relates to the large proportion of newcomers who speak Spanish—is closely intertwined. (“Bid to Make English the ‘National Language’ Raises Many Questions,” this issue.)

About 4 percent of the nation’s 666,000 GED test-takers take the Spanish version. A smaller proportion take it in French. Some states, such as California, don’t distinguish on GED certificates or high-school-equivalency diplomas what language the GED test was taken in.

Debate over what language should be used in GED preparation classes and testing has mostly been confined to those who work in adult literacy.

“Within the adult education world, there’s a fair amount of controversy as to whether the [GED] instruction is offered in Spanish or English,” said Cheryl L. Keenan, the director of the division of adult education and literacy in the U.S. Department of Education. The federal government provides states about $560 million a year in grants for adult basic education, but doesn’t prescribe or track whether the aid is used for instruction in English or another language, she said.

The national GED test, designed to assess core high school knowledge, is developed by the GED Testing Service, an arm of the Washington-based American Council on Education. The Spanish version is basically a direct translation of the English-language version that has been field-tested with bilingual test-takers, explained Lyn Schaefer, the director of test development for the testing service.

Jim J. Boulet Jr., the executive director of English First, a Springfield, Va.-based organization that wants to make English the official language of the United States and opposes bilingual education, said last week that programs such as Spanish GED classes, which he acknowledged he hadn’t previously known existed, are a “terrible idea” and deserve closer scrutiny.

“The money should be spent on English classes,” he said.

Cathy Balestrieri, a vocational-program administrator in New York’s Westchester County, agrees that immigrants need to learn English, but says it also makes sense to provide them with proof of their skills in Spanish as part of their education.

“If a kid has zero credits and is 17, he doesn’t want to be sitting in a 9th grade class,” she said. “What we’re doing with our marketing and recruiting is saying, ‘You’re going to make yourself more marketable if you have the Spanish GED, some English, and a trade.’ ”

Getting the Word Out

The GED test is taken mostly by adults who did not receive a high school diploma because they dropped out or never met state graduation requirements. The exam is a series of five tests that cover mathematics, science, reading, writing, and social studies. In 2004, the average age of a GED test-taker was 25, though 32 percent of test-takers that year were ages 16 to 18.

The number of people taking the test dropped dramatically from 2001 to 2002, when the test was made more difficult, Ms. Schaefer of the GED Testing Service said. The number of all GED test-takers has increased each year since 2002, but still has not reached the peak of nearly 1.1 million in 2001.

Some state administrators of the GED say the demand for the Spanish version of the test is growing in regions of their states with a lot of Latinos.

Robert M. Berezny, the state administrator for GED testing in New Jersey, said he’s planning to open at least one testing center next year geared completely to providing the GED in Spanish, staffed with Spanish-speakers who can get the word out about the test.

“The belief in the community is that if they’re able to take the test in Spanish, more people would come out and take the test,” he said.

Don Soifer, the executive vice president of the Lexington Institute, a think tank in Arlington, Va., that generally opposes bilingual education, said he doesn’t have a problem with immigrants who have attended U.S. schools only for a short time, or not at all, taking the GED test and preparation coursework in Spanish.

But he added: “If the ability to offer and take the GED in Spanish provides an incentive for schools to put the limited-English-proficient kid on a GED track rather than a regular high school education track, that undermines the goals of inclusiveness.”

New York Program

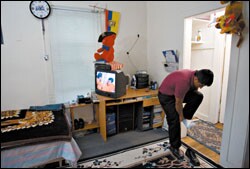

Here at a Spanish-language GED program in Yorktown Heights, N.Y., located north of New York City in Westchester County, educators try to strike a balance between helping immigrant youths get a regular diploma in their home schools and encouraging them to try alternative schooling if they are running out of time.

Many of the 35 youths enrolled at the Putnam/Northern Westchester Board of Cooperative Educational Services, or BOCES, who are working on a Spanish GED say they chose that path because it’s not feasible for them to get a regular high school diploma.

It’s also uncertain if those in the group who are undocumented—a majority of them, according to their teachers—will get papers to live legally in the United States anytime soon. But it is possible, the students say, to get a GED in Spanish.

For example, 20-year-old Marco Cuzco, an immigrant from Ecuador who is waiting for the results from his recent Spanish GED test, transferred from a regular high school to the BOCES program last year in 11th grade after he realized he had only 11 of the 21 credits he needed to graduate. He had passed only two of the five required New York Regents exams.

Mr. Cuzco arrived in the United States when he was 15 and can converse well in English, but he said he doubted that he could pass the English Regents exam. “I learned English fast, but for the Regents English, you have to speak and write like an American student,” he said.

In addition, his father, with whom he lives, was pressing him to devise a plan to support himself. So the younger Mr. Cuzco opted for a school day in which he prepared for the Spanish GED for two hours, took classes in English as a second language for two hours, and studied plumbing—in English–for two hours.

The Putnam-Northern Westchester BOCES offers a number of vocational programs, including cosmetology, masonry, and culinary arts, in Spanish. One of those programs—a course on becoming a home health aide—is designed for students who don’t have papers to live legally in this country and aren’t eligible to sit for state licensing exams because they aren’t legal residents, said Ms. Balestrieri, who is the principal of the BOCES secondary education vocational program.

Ms. Balestrieri said that most of the students in the Spanish GED program arrived in the United States at age 16 or older, without any English skills, and had stopped their formal education at the 5th or 6th grade in their home countries.

She explained that the students in the BOCES secondary school program are enrolled in any of 18 home school districts in the region, which pays the cooperative-services board about $10,000 in tuition a year per student.

“We want the students to learn English,” said Fernando Gomez, who teaches the Spanish GED classes here. But because their formal schooling in their home countries was interrupted, his students need to improve their literacy skills in their own language at the same time they are learning English, he added.

“It’s not a problem of English or Spanish. It’s a problem of comprehension,” he said.

A Graduate’s Experience

During a recent lesson, Mr. Gomez asked his students to write a summary of a newspaper article about the national immigration debate. He reviewed their work with them to make sure they included an introduction, one or two paragraphs of explanation, and a conclusion—skills that he says are required on the Spanish GED.

In another class, he invited a former student who is attending community college to speak about how a GED in Spanish was a steppingstone to more education.

Oscar, whose last name is being withheld because he is undocumented, earned his GED in Spanish in 2004 through the BOCES program. He told the students that he’s had to study much harder in college than he did in the BOCES program. “Everything is in English,” he said in Spanish.

Oscar, 22, hopes to transfer to a four-year college and become a Spanish teacher.

Mr. Gomez used Oscar’s story to make a positive point to the class: Lack of documented status should not deter an immigrant from trying to get an education in this country.

“Here is a student without papers,” he said, speaking of Oscar. He told his students to consider Oscar’s situation should Congress provide a way for millions of undocumented immigrants to become legal U.S. residents.

“In the waiting line for a job is Oscar and someone else who doesn’t have the same level of education,” he said. “Who is going to get the job?”