Editor’s Note: Before the election, Louisiana state Teacher of the Year Chris Dier was already planning what he would say to his class if uncertainty prevailed on election night. Here’s how he will be approaching his high school U.S. history class today:

Waking up to teach the day after the presidential election of 2016 was one of the most surreal moments of my more than decade-long teaching career. The demographics of the high school where I was teaching four years ago were roughly 50 percent white and 50 percent Black, Indigenous, and students of color. That morning, some of the students were excited; others were visibly upset. And as they walked into class, I handed them a sheet of loose-leaf and asked them to jot down whatever thoughts they had about the election. There was no rubric.

Students eagerly took pen to paper. I noticed one student write something brief and put her pencil down as other students continued to write. Her paper read, “I want to be in this country because I love it. I don’t know if this country wants me back now though.” I’ll never forget those words or the emotions on her face. I still have all of their writings from that day.

What followed was an interesting conversation. By that point in the year, I had taught my students for almost four months, and we’d had meaningful discourse about a variety of topics. Fortunately, despite the range of political opinions and emotions, the class was a safe space for dialogue. We felt comfortable with each other, and we trusted each other.

Contested elections have dire consequences, especially on already marginalized populations, and that is worthy of exploration.

Regardless of the outcome, we educators must show up for our students, especially as history tells us that contested elections have lasting consequences.

This time around, I still plan to let my students process their emotions; addressing their social-emotional needs takes precedence over finding teachable moments. Regardless of our political leanings, events of this magnitude take a toll on these young people. My students are already feeling the pressures of high school while navigating a pandemic, attending virtual or hybrid classes, and witnessing protests addressing racial inequities and police brutality. Many are in families bearing the economic burdens brought on by COVID-19. They are listening to the adults in their lives and on screens pull them in different directions. It’s all-encompassing and trauma-inducing.

After providing them with an outlet to release their thoughts, I will discuss the election head on.

Educators should not ignore controversy solely because it’s challenging. Generation Z already understands how politics can meaningfully shape their lives. Students feel the weight of hot-button issues. They comprehend the climate is changing to an extent that will damage their futures if we do not act now. They feel the impact of systemic racism, homophobia, and transphobia. Many who want to attend college are aware that they will accumulate significant debt to achieve that dream.

Apolitical classrooms are not a viable option. As long as we prioritize the emotional well-being of the students, the possibilities for teaching this election are endless.

So, on Wednesday I plan to allow my students to drive the conversation with their own questions, concerns, and thoughts. We already have established discussion norms centered on tolerance, understanding, and empathy. Although I’ve never met many of them in person, I have developed a relationship of trust with my students. I begin every virtual class with an opportunity for them to share news about their personal lives. I start it off by opening up about mine.

They know that my dog pesters me while I’m trying to teach them. I know the sports they play, the music they listen to, the books they read, the Netflix shows they enjoy, the video games they play, and other tidbits about them. These human connections make the difficult conversations easier.

As a high school U.S. history teacher, I want to use this election as a way to educate them about previous presidential elections when the results were not immediately known. We might explore the origins of the Electoral College and debate its relevance today. If we have no clear winner by Wednesday morning, I plan to push the conversation toward an exploration of the contested presidential election of 1876.

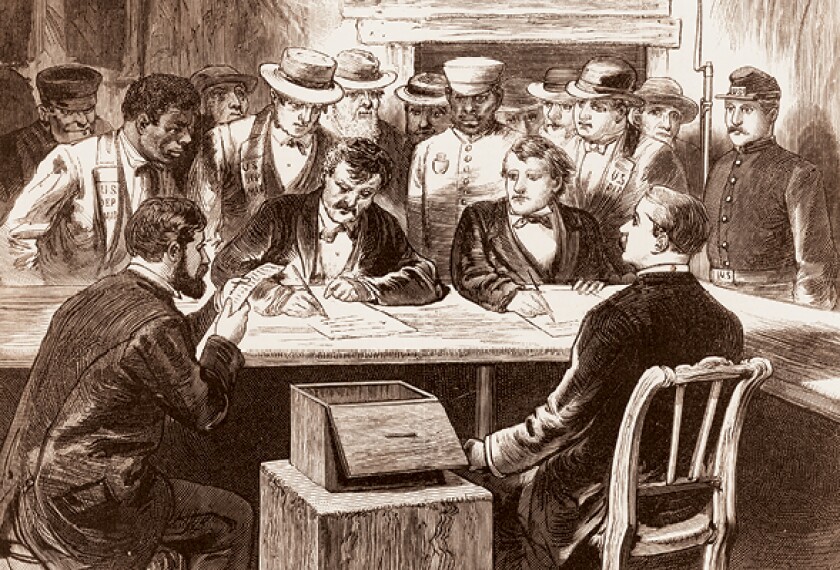

My students have taken a particular interest in Reconstruction--the era after the Civil War which was marked by large-scale efforts to address the social, political, and economic inequities of African Americans following the abolition of de jure slavery. During Reconstruction, the federal government occupied the South and offered protection to freedpeople. Black men were granted suffrage and hundreds of Black Americans filled political positions across the nation.

Although there were advancements to improve racial equality, Reconstruction efforts were ultimately defeated by racist restrictions on freedpeople, violent and widespread backlash from white supremacists, and the North’s increasing apathy toward the South. Reconstruction ended with the heavily contested election between Gov. Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio, a Republican, and Gov. Samuel J. Tilden of New York, a Democrat. (The ideological alignments of the two parties was significantly different in the 19th century compared with today.)

The outcome of the race depended on the disputed returns from Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina--the last remaining states where Reconstruction-era Republicans maintained power. Tilden won the popular vote, but was short on the Electoral College votes needed to win. A secret committee negotiated a shadowy, backroom compromise in which Democrats conceded to a Hayes victory on the condition that Republicans withdraw all federal troops from the South.

The Compromise of 1877 marked the end of Reconstruction and left African Americans across the South unprotected. And it allowed southern states to solidify Jim Crow segregation, leading to a dramatic increase in lynchings. It ushered in a new wave of voter suppression policies through the levying of poll taxes, grandfather clauses, and literacy tests. The results of this contested election uplifted white supremacy, reversed Reconstruction gains, and set the template for race relations until Civil Rights movement—almost a century later.

Contested elections have dire consequences, especially on already marginalized populations, and that is worthy of exploration--then and now.

There is enormous hype surrounding our national elections, especially one as controversial as this year’s. As educators, we have an opportunity to harness that energy, to make it productive for students and their growing understanding of our history, particularly as it pertains to their young lives. There is no question that teaching this election will be a challenge, but we will only do our students justice by addressing their legitimate concerns and engaging them in unbiased ways that support their emotional well-being, intellectual growth, and human dignity.

Our students are already empowered. This November, I intend to use the space we’ve cultivated in our virtual classroom to allow them to best assert their power for the change they wish to see. The future of our democracy depends on it.