With a school population of 210, and a K-12 staff of 25, there’s roughly one teacher for every major subject, and few of them stay in the isolated community much longer than three years. Everyone and everything comes by boat, including the iPods destined for the Advanced Placement French class, one of six such college-level classes in a school that until this year had just one.

But in this rural setting where the lobsterman is king and where many students follow in their families’ footsteps, school leaders have joined a six-state effort by the National Governors Association aimed at making AP classes more widely available, recruiting nontraditional students to enroll, and working to make sure those students succeed in the college-level courses.

Vinalhaven’s experiment is being mirrored nearly three hours away in the city of Portland, where the 1,050-student Portland High School is working to fill its AP classes with more minority and low-income students. The students targeted include many from the city’s booming Somali and Sudanese immigrant populations who came to the United States with little or no schooling to escape civil wars in their countries.

These two Maine schools—like the dozens of other rural and urban ones around the country participating in the NGA pilot program—face common barriers to expanding their Advanced Placement programs. They include a lack of teacher training, little money to create new classes, a curriculum in earlier grades that isn’t rigorous enough to prepare students for AP, and difficulty in getting minority and low-income students to enroll.

But participants say the NGA initiative is showing impressive early results in overcoming those barriers. In the first full year of the two-year grant program, which awarded states $500,000 each, the 49 participating schools have increased their minority enrollments in AP classes by a combined 52 percent, and the number of low-income students by 57 percent. Overall, the schools have increased their AP offerings by 27 percent.

“That speaks to the fact that there is a great hunger out there for more challenging coursework,” said David Wakelyn, an NGA senior policy analyst who is directing the grant project, which field-tests AP strategies in at least one rural and urban school in each of the six pilot states. “We’ve been afraid of asking kids to do more. This is one of several ways to restore value to the diploma.”

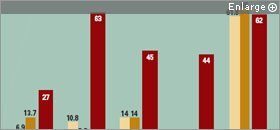

Nationally, minority students, particularly African-Americans, are underrepresented in Advanced Placement classes and typically score lower on AP exams than do white students.

SOURCE: College Board

The strategies in Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Maine, Nevada, and Wisconsin, the pilot states, are similar: a focus on training teachers, recruiting students, and bolstering the middle school and lower high school curriculum leading up to AP classes.

Each of the states is going further and customizing its approaches.

Nevada has started a summer program to get students ready for AP. One school in Wisconsin worked on recruiting students in cohorts, so they’d know others who were enrolling. Kentucky is pushing its teachers from rural Appalachia and urban Fayette County to build a professional learning team. Georgia is building a pool of teachers who are ready to teach AP. Alabama is using “vertical team training” that gets teachers in earlier grades to beef up their curricula so students are better prepared for rigorous coursework. And Maine is using more-experienced AP teachers to mentor new ones.

The AP Model

Advanced Placement, a program of the New York City-based College Board, offers high schoolers an opportunity for college credit in 22 subjects, ranging from high-level math and science to fine arts, if they score well on a standardized, national end-of-course exam. About 24 percent of students in the high school class of 2006, or 666,067 students, took at least one AP exam during their high school careers, according to a College Board report issued in February.

Of those who took exams, 61 percent scored 3 or better on a 5-point scale. A score of at least 3 is considered a predictor of college success; that score is enough for many colleges to offer students credit for an AP course. Increasingly, schools and states are including AP as a component as they redesign their high school classes and make them more demanding. In the 49 schools participating in the NGA program, teachers and principals say they already are seeing results outside of AP classes.

“The real lasting effect is the training for our teachers—and not just AP teachers,” said Tommie Howell, the principal of the 1,600-student Bainbridge High School, in rural southwest Georgia. His school, one of nine in his state taking part in the project, went from offering no AP classes to seven, which enroll a total of more than 100 students. “Down in the middle schools, they are ramping up their entire sequence so students are better prepared,” Mr. Howell said.

All six states in a program to increase AP enrollment saw promising early results at their pilot sites.

*click on each state name to see detailed information.

HTML; } ?>

| Alabama | |

|---|---|

| Number of students in AP courses 2005-06 (baseline): | 202 |

| Number of students in AP courses 2006-07: | 298 |

| Percent change at pilot sites: | 48% |

| Percent of minority enrollment in the state: | 36% |

| Percent of minority students in AP pilot sites: | 65% |

| Number of minority students in AP courses 2005-06 (baseline): | 64 |

| Number of minority students in AP courses 2006-07: | 152 |

| Percent change at pilot sites: | 138% |

| Three high schools each in Huntsville and Butler County school districts are participating. To recruit students, the schools used the PSAT and AP Potential, which uses PSAT scores to predict success on AP exams. The state is working with schools on “vertical team training” in grades 6-12, which helps teachers in earlier grades get students ready for more rigorous coursework. | |

| Collapse | |

HTML; } ?>

| Georgia | |

|---|---|

| Number of students in AP courses 2005-06 (baseline): | 1,237 |

| Number of students in AP courses 2006-07: | 2,018 |

| Percent change at pilot sites: | 63% |

| Percent of minority enrollment in the state: | 36% |

| Percent of minority students in AP pilot sites: | 37% |

| Number of minority students in AP courses 2005-06 (baseline): | 364 |

| Number of minority students in AP courses 2006-07: | 601 |

| Percent change at pilot sites: | 65% |

| Nine high schools in nine districts are participating. Schools used AP Potential, class invitations, and one-on-one student conferences to recruit students to AP classes. Grant money was used to buy lab equipment for AP science classes. Some schools also are using vertical team training. | |

| Collapse | |

HTML; } ?>

| Kentucky | |

|---|---|

| Number of students in AP courses 2005-06 (baseline): | 1,413 |

| Number of students in AP courses 2006-07: | 2,119 |

| Percent change at pilot sites: | 50% |

| Percent of minority enrollment in the state: | 11% |

| Percent of minority students in AP pilot sites: | 19% |

| Number of minority students in AP courses 2005-06 (baseline): | 93 |

| Number of minority students in AP courses 2006-07: | 151 |

| Percent change at pilot sites: | 62% |

| Nine high schools in two districts—Fayette and Pike counties—participate. To improve professional development, teachers and administrators in these two districts are jointly training, devising curriculum strategies, and working through problems. | |

| Collapse | |

HTML; } ?>

| Maine | |

|---|---|

| Number of students in AP courses 2005-06 (baseline): | 371 |

| Number of students in AP courses 2006-07: | 631 |

| Percent change at pilot sites: | 70% |

| Percent of minority enrollment in the state: | 3% |

| Percent of minority students in AP pilot sites: | 16% |

| Number of minority students in AP courses 2005-06 (baseline): | 12 |

| Number of minority students in AP courses 2006-07: | 33 |

| Percent change at pilot sites: | 175% |

| Eight schools in seven districts participate, with Portland’s being the largest. The state pairs new AP teachers with mentors, and holds monthly meetings with the school principals to build a strong leadership network. | |

| Collapse | |

HTML; } ?>

| Nevada | |

|---|---|

| Number of students in AP courses 2005-06 (baseline): | 768 |

| Number of students in AP courses 2006-07: | 1,239 |

| Percent change at pilot sites: | 61% |

| Percent of minority enrollment in the state: | 29% |

| Percent of minority students in AP pilot sites: | 81% |

| Number of minority students in AP courses 2005-06 (baseline): | 520 |

| Number of minority students in AP courses 2006-07: | 681 |

| Percent change at pilot sites: | 31% |

| Five high schools, all in Clark County, are participating this year; the state is adding three more schools next year. The state and schools set up a four-week summer pre-AP program to give students, who were identified as potential successes by counselors, extra AP help in English and math. | |

| Collapse | |

HTML; } ?>

| Wisconsin | |

|---|---|

| Number of students in AP courses 2005-06 (baseline): | 1,851 |

| Number of students in AP courses 2006-07: | 2,060 |

| Percent change at pilot sites: | 11% |

| Percent of minority enrollment in the state: | 10% |

| Percent of minority students in AP pilot sites: | 29% |

| Number of minority students in AP courses 2005-06 (baseline): | 203 |

| Number of minority students in AP courses 2006-07: | 255 |

| Percent change at pilot sites: | 26% |

| Twelve schools in nine districts are participating, with the largest being Madison. Schools are recruiting potential AP students, particularly minority students, in groups, so they’ll know others who are enrolling. The state is working to build a cadre of leaders within each school who will take charge of the AP expansion. The state also sponsored a five-day “summer splash” to get teachers, administrators, and guidance counselors trained in AP expansion efforts. | |

| Collapse | |

SOURCES: National Governors Association and Education Week

That kind of integrated approach brings the most success in better preparing students for college, said Trevor Packer, the executive director of the College Board’s Advanced Placement program. Adding a bunch of AP classes alone isn’t effective, he said, since “AP rigor can come as a system-shock if you don’t have the foundation. If the approach is quantity over quality, then the strategies don’t work.”

The NGA pilot program’s approach—throwing the doors to AP wide open to anyone who wants to participate, in the hope of attracting more minority and low-income students—remains the exception.

Nationally, a majority of schools screen applicants and limit student participation in AP, while 48 percent of schools say they use open enrollment or student desire as a factor in allowing students to take the courses, according to the College Board.

Such limits can skew the makeup of AP classes. Mr. Packer noted that while about 80,000 students nationally are taking AP Biology now, there are 800,000 students of similar academic backgrounds not enrolled in such classes for some reason.

Minorities—black students, in particular—are underrepresented in most AP classes. While 13.7 percent of U.S. high school seniors are black, those students made up just 6.9 percent of AP exam-takers, according to the College Board’s report on the class of 2006.

Separate data show a similar picture for low-income students, as measured by those who qualify for subsidized school lunches. According to the College Board, low-income students made up just 12.2 percent of students who took a 2006 AP exam. For many, the $83-per-exam fee may be perceived as a barrier, although federal and state subsidies pick up all or much of the cost for low-income students.

In many schools, the problem of getting underrepresented students into AP classes is rooted in fundamental identity issues many teenagers face.

“If there’s no one else like you in class, it’s very difficult to be there,” said Chrys Mursky, the Wisconsin Department of Education’s consultant for gifted-and-talented and for Advanced Placement programs.

And the barriers can be cultural, too, as in the cities of Kentucky and the rural parts of that state.

“These places have a long history of undereducation,” said Linda Pittenger, Kentucky’s director of secondary and virtual learning.

Recruiting Strategies

Most of the NGA pilot program’s schools are recruiting students, particularly minority students, in groups. Schools are holding parent-information nights, mailing class invitations home, and hosting AP open houses. In all the states involved, individual teachers are recruiting students to join AP classes, just as they would recruit them for sports teams.

In Maine, which is posting the biggest percentage gains among the pilot states in recruiting low-income and minority students to AP classes, invitation letters sent to parents were particularly effective at Portland High.

Eighteen-year-old Keshia White said she probably wouldn’t be in AP Statistics—one of the school’s six new AP classes—had it not been for the letter her parents got and their insistence that she try that harder class.

“It’s a lot more work, but I think it’s worth it,” said Ms. White, a senior who is planning a career in accounting.

On the island of Vinalhaven, Philip Hopkins, a senior, probably wouldn’t be in AP now, either, had it not been for the NGA program. He already has his lobster boat and plans to continue his family’s fishing business, but is planning to attend a vocational education program in mechanics on the mainland in case the business goes sour.

For many students, including Mr. Hopkins, the notion of AP—with its more-demanding coursework and college-level lessons—can be intimidating. But with some coaxing from teacher Erica Hansen, he joined her rigorous AP Studio Art class, which includes among its requirements an extensive portfolio and a well-written “artist’s statement.” He found he was up to the challenge.

“I thought it would be a lot harder because it was AP, but it really hasn’t been,” said Mr. Hopkins, who is specializing in design.

While rural and urban districts have some common challenges in expanding their AP programs, they also face their own distinctive issues.

In many rural districts, for example, the small population has sometimes made it difficult to justify an advanced class for just a few students. Many rural schools, like Vinalhaven, have just one science teacher, one social studies teacher, and one English teacher, so finding time for those teachers to lead an AP class is tough.

Vinalhaven School Principal Mike Felton teaches one of the school’s six AP classes—world history. He said the benefits for students go beyond learning the history of Chinese dynasties.

“One of the challenges here is the transition for students between island life and college,” Mr. Felton said. Though many students will stay on the island after college, he said, about 80 percent go to some form of college, and many students say they’ll never return to live here.

“This is allowing our students to get a feel for what it will be like” after they leave the island, Mr. Felton said.

Adding several different science classes can be especially difficult in rural districts because laboratory equipment is expensive. In Vinalhaven, the NGA grant helped buy iPods for the AP French class so students could listen to lessons and develop their own podcasts.

On the flip side, while urban districts may have enough teachers and students to justify classes, their students often aren’t adequately prepared, according to Mr. Packer, of the College Board. Those larger schools often have many competing academic priorities that all cost money.

“One of my biggest challenges is that we’re still a poor state; we don’t have the computers to do AP exams online, or the microphones,” said Philip Thibault, who is teaching his first AP French course at Portland High School.

In addition, many urban schools have existing AP programs, so efforts to open up the program to more students can meet with resistance among teachers and other staff members.

“Our AP program used to be more exclusive. We’ve had to have a change in mind-set with teachers, especially those who had been here for a while and think the classes are only for the top students,” said Sue Mullen, a guidance counselor at Portland High, where 35 percent of students are multilingual and about 120 high school students are in English-language-learner classes. Several of those students are now in AP classes.

There’s also some resistance to expanding AP among Portland’s top students.

“I like the classes when they’re more homogeneous, when teachers don’t have to slow down for some students,” said Adrian Williamson, a senior, who had just finished a discussion in his AP English class about Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

Sustaining the Initiative

Though Advanced Placement participation in the NGA pilot schools is up, the schools, teachers, and policymakers won’t know how well students fare until later this year. Students take their AP exams this month and will find out their results in July.

It also is unclear how the efforts will fare once the NGA grant runs out in December, since the money has been used to train teachers, buy supplies, and help defer AP exam fees.

“One of the frustrations at the state, district, and school level is we know what has to be done, but we don’t always have the money,” said Gloria Dopf, Nevada’s deputy superintendent of instruction, research, and evaluative services. She said her state will continue to ramp up its AP efforts after the grant money runs out.

Some states are, on their own, making AP a priority.

This year’s budget in Alabama set aside $1 million to help schools train teachers and expand their course offerings; the state department of education is requesting $3 million for the coming budget year. Wisconsin is in the second year of a state-funded grant program that awards schools $300 per student in a newly added AP course.

In Maine, the success of the AP-expansion efforts won’t be measured by students’ scores, especially in the first few years of the program, officials say.

“We’re trying really hard to show scores don’t matter,” said Wanda Monthey, the policy director of standards, assessment, and regional services for the Maine Department of Education. “If we see a lot of 3s, 4s, and 5s on the students’ [AP] tests, then we’ll know the schools screened out other kids.

“And that’s not what this is about,” she said. “We’re opening this up to more students.”