By the end of their first semester in high school, two 9th grade students have similar test scores and identical grades—mostly C’s, a couple of D’s, and an F. A year later, though, the academic paths of these two students diverge widely. One is still in school. The other has dropped out.

| Feature Stories |

|---|

| The Down Staircase |

| Adding It All Up |

| Opening Doors |

| Student Profiles |

| About This Report |

| Table of Contents |

What explains the difference?

According to research on students who drop out, any number of factors might have combined to push the second student out the door. Say, for instance, that he or she had repeated 2nd grade. Some studies suggest that being retained even once between 1st and 8th grades makes a student four times more likely to drop out than a classmate who was never held back.

The more unfortunate student might also have changed schools midway through the year or racked up a couple of suspensions.

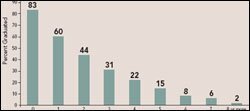

Researchers at the Consortium on Chicago School Research at the University of Chicago used the on-track indicator to determine whether Chicago public school students were on or off track to graduate from high school. The numbers of course credits and passing course grades were found to be strong predictors of graduation. Students considered on track had earned at least five full course credits and received no more than one F as a semester grade by the end of freshman year.

*Click image to see the full chart.

SOURCE: Consortium on Chicago School Research at the University of Chicago, 2005

Repeating a grade, changing schools, and behavior problems are among the host of signals that a student is likely to leave school without a traditional diploma. In studies conducted since the 1970s, scholars have isolated dozens of such predictors, most of which tend to build on one another like the proverbial straws on the camel’s back, and increase the likelihood that a student will fail to graduate.

Now, experts say, schools ought to capitalize on that knowledge to flag students who are at risk of dropping out. That way, they can intervene early and give floundering students the extra help they need to beat the odds stacking up against them.

“For many youngsters, these difficulties appear early in the game,” says Karl L. Alexander, a sociologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “If we could figure out how to address them early . . . they’d be a lot better off and so would we.”

Cumulative Process

According to researchers, no one factor causes students suddenly to decide to drop out. The process is long-term and cumulative. And it turns out that test scores and poor grades, while an important and consistent part of the mix, are not necessarily the only determinants of which students drop out and which persevere.

For example, in a recent survey paid for by the Seattle-based Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, 88 percent of the dropouts interviewed said they were earning passing grades when they left school. Seventy percent were confident that they could have graduated had circumstances been different.

But the predictor that “trumps everything else,” in Alexander’s view, is whether a student repeated a grade in elementary or middle school. With Doris Entwistle, a fellow sociologist at Johns Hopkins, he has been tracking 790 students who started 1st grade in inner-city Baltimore public schools in 1982.

Over the course of the intervening years, the researchers have seen a strong link develop between repeating a grade and dropping out. Sixty-four percent of the students who had repeated a grade in elementary school, and 63 percent of those who had been retained in middle school, eventually wound up leaving school without a diploma. In all, 40 percent of the original group never made it to graduation.

“People may think there’s just a stigma when it happens in the older grades,” Elaine M. Allensworth, the associate director of the Consortium on Chicago School Research at the University of Chicago, says of being held back. “But just being old for grade seems to matter.”

Excessive mobility can be another warning sign, says Russell W. Rumberger, a researcher at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His studies, drawing on nationally representative student data sets, suggest that students who move twice during their high school years are twice as likely not to graduate as their peers whose enrollment is more stable.

A disrupted school career, Rumberger reasons, may be a stand-in for more serious issues, such as behavior problems or a chaotic home life.

Excessive absenteeism, too, is a telltale sign that a student is slowly disengaging from school. The Gates Foundation survey, for instance, shows that the dropouts its researchers interviewed reported a pattern of “refusing to wake up, skipping class, and taking three-hour lunches.” Each absence, the dropouts said, made them less willing to go back. In all, 59 percent to 65 percent of the dropouts interviewed for the study said they missed classes often the year they dropped out.

Then, there are background factors that commonly raise a student’s risk of dropping out: being born male, or poor or black or Latino, having friends and family who never finished high school, or becoming pregnant.

Researchers have seen a strong link develop between repeating a grade and dropping out.

The problem with family and demographic predictors, though, is that they don’t offer much guidance on how schools can keep students on track to graduate.

“In a national sample, yes, those kids do have higher dropout rates, but it doesn’t help at the practical level, because all the kids at a lot of these schools with high dropout rates are poor and minority,” says Robert Balfanz, a research scientist at the Center for Social Organization of Schools at Johns Hopkins.

Balfanz is among a small number of researchers who have begun working in recent years to pick out constellations of school-based predictors that educators can use to construct early-warning systems and head off dropout problems.

“By first semester freshman year, we can really predict who’s going to drop out later on,” says Allensworth of the Chicago consortium. She and her research partners there have found that accumulating fewer than five course credits and two or more consecutive F’s by the end of that first semester is enough to put students on the road to an early school exit.

“Lots of students have marginal academic performances in their freshman year, and schools think, ‘Oh, well, they’re doing OK,’ ’’ she says. “But these students are also at high risk for dropping out eventually by the third, or fourth, or fifth year of high school because it’s going to start building up for them.”

Starting Early

Other experts suggest that educators should start the search for signs of trouble even earlier.

“I would say middle school is not too early,” says Rumberger. Both he and Balfanz have successfully tested out sets of school-level indicators that identify students at risk for dropping out by 6th or 7th grade.

The more recent of the two models—Balfanz’s—flags 6th graders who meet three criteria: They attend school less than 80 percent of the time, received a poor final grade from their teachers in behavior, and were failing either mathematics or English.

Along with Liza Herzog, a researcher from the Philadelphia Education Fund, Balfanz tested that set of indicators with 12,000 to 13,000 Philadelphia students who started 6th grade in 1996. Of the students in that group who eventually dropped out, more than half fit the profile.

Over the 2006-07 school year, Balfanz says, three Philadelphia middle schools will launch a pilot project to use the indicators to identify students for special help in the form of mentoring, Saturday classes, or more intensive assistance.

The indicator work follows up research that Balfanz did to identify the 900 to 1,000 schools across the nation with the weakest “promoting power”—schools, in other words, that fail to graduate half or more of their students on time.

By targeting both problem schools and the students within those schools who are most likely to drop out, he figures, the United States could cut its dropout rate by as much as a quarter.

“You could identify the schools that produce most of the dropouts, and fundamentally transform them or replace them with something better,” Balfanz says. “Then beyond that whole-school reform, provide mentors, or additional school supports for that subset of students who are at even greater risk.”