Includes updates and/or revisions.

National tests in several core subjects could be eliminated or scaled back over the next five years without more federal funding, the officials who set policy for the National Assessment of Educational Progress say.

Scheduled exams in economics, foreign language, geography, and world history could be canceled if funding remains flat, as is projected. Moreover, some grade levels would not be tested in civics, U.S. history, and writing, and the NAEP long-term trend tests in mathematics and reading, which have been conducted regularly over the past 40 years, would be given in 2008, but not in 2012.

“The schedule of assessments issued is indeed serious. … With the given money and the contracts to be had, there is a shortfall,” Darvin M. Winick, the chairman of the National Assessment Governing Board, or NAGB, which sets policy for the program, told the board Nov. 16 at its quarterly meeting here. “This is not yet engraved in stone,” he said, “but we’re certain you will have to face up to some of those changes.”

Decisions on those changes would have to be made well before the tests are scheduled because of the lengthy process of crafting test questions, selecting representative samples of schools and students, and other preparations. The board, for example, would have to decide on whether to proceed with the geography test by this coming February.

For more stories on this topic see Testing & Accountability.

For background, previous stories, and Web links, read Assessment.

The news came as a blow to several organizations representing subject-area teachers and researchers, which have lobbied over the past decade for an expansion of the federally sponsored testing program, known as “the nation’s report card,” as a way to improve instruction in those areas. Pointing to research showing that content tested on state and national exams garners a greater proportion of instructional time, the groups have argued that including their subjects in the national-assessment program raises their importance in the curriculum.

Amid concerns that some core subjects are being marginalized under the No Child Left Behind Act, and calls from lawmakers and business leaders for schools to do a better job preparing students for the global economy, some observers say NAEP tests are more important than ever. The federal education law requires annual testing in reading and math in grades 3-8 and once in high school. (“Schools Urged to Push Beyond Math, Reading To Broader Curriculum,” Dec. 20, 2006.)

“This news causes widespread dismay at a time when the history curriculum is shrinking dramatically,” said Theodore K. Rabb, a professor emeritus of world history at Princeton University and the board chairman of the National Council for History Education, based in Westlake, Ohio. “If this is happening nationwide, organizations like NAGB are responsible for doing something about it. It shouldn’t just be about whether they have money for it; they have a civic duty to do this.”

Members of the council embarked on a letter-writing campaign earlier this year to urge Congress to strengthen history requirements under the nearly 6-year-old NCLB law. A bill being considered by the U.S. Senate would require pilot testing of a state sampling of students on the U.S. history NAEP, in addition to the national sample.

Gearing Up—for Naught?

Foreign languages, meanwhile, have been gaining attention for what advocates see as such coursework’s importance in preparing students for an increasingly global society.

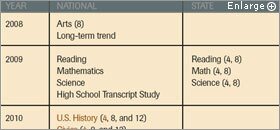

SOURCE: National Assessment Governing Board

“It’s ironic that NAGB [has to make this decision] as foreign-language learning is on the radar screen in all sectors, including the government, business, and the community at large,” Brett Lovejoy, the executive director of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, said in a statement. The group’s annual convention this month in San Antonio drew a record-high 7,000 attendees. “Increasingly, parents and students are seeking out language-learning opportunities,” Mr. Lovejoy said.

The national-assessment board approved the NAEP test of Spanish-language skills in 2000, but the planned administration of the test was delayed after participation in a pilot fell short of the necessary standard for ensuring the validity of results. It was rescheduled for 2012. (“National Foreign-Language Assessment Delayed Indefinitely,” March 17, 2004.)

After advocacy groups had lobbied for the addition of economics and helped devise the framework, the first test of that subject was given in 2006. That test for 12th graders is also scheduled for 2012, along with the one in world history. Both are in danger of being eliminated, however.

The geography assessment, first given in 1994, has been credited with increasing the time and attention paid to the subject.

Higher Costs

A new contract between the National Center for Education Statistics and outside organizations that design, conduct, and score the tests and disseminate the results outlines the testing schedule through 2012. The contract requires the testing of the arts next year, reading and math in 2009 and 2011, and science in 2009. The No Child Left Behind law requires states to participate in the math and reading tests in grades 4 and 8.

In 2010, samples of students in the 8th and 12th grades would still be tested in U.S. history and civics, but those exams would not be given to 4th graders as planned. The writing assessment, scheduled for 2011, would be given only to 8th graders.

A special study of students’ technological literacy, which had been planned for 2012, would be scrapped.

The revised schedule is based on budget projections, and assumes that funding for the program in fiscal 2008 would be consistent with previous years, or about $88 million. The money for NAEP comes out of the U.S. Department of Education’s budget. Fiscal 2008 started Oct. 1. President Bush vetoed a spending measure Nov. 13 that would have boosted funding for NAEP to $99 million, but the additional $11 million was earmarked for expansion of the urban district assessments in reading and math, and inclusion of 12th graders in the program.

Even if that funding held steady through 2012, it would not cover the full slate of tests scheduled. Conducting a large-scale assessment program with representative samples of students in grades 4, 8, and 12 is complex and costly, said Peggy G. Carr, the associate commissioner of assessment for the NCES, the arm of the Education Department that administers the tests. Additional assessments and studies, travel costs, and fees for psychometricians and consultants have increased considerably in recent years, she added, pushing costs up.

“There’s not a lot of understanding of how much more expensive things have become,” Ms. Carr said. “We wanted to identify those assessments that have less impact on the current portfolio of the program” that could be scaled down to contain costs.

With the validity of the pilot assessment in foreign language in question, that Spanish test was a logical target, she said. Because the long-term-trend test will be given next year, officials believed the program would not suffer from the change. Even so, Ms. Carr said she expects that subject-area experts will not be happy about any changes that are made.

“The constituents,” she said, “are going to be concerned.”