Attempts by lawmakers to update—or totally overhaul—FERPA continue to mount.

This week, two more bills aimed at the country’s most prominent current federal law protecting student data privacy, officially known as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, were introduced in Congress.

On Wednesday, U.S. Senators Edward Markey (D-Mass.) and Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) reintroduced their “Protecting Student Privacy Act.” The bill would prohibit the use of students’ personally identifiable information for advertising and marketing purposes and seek to minimize the amount of such information that is transferred from schools to private companies, among other changes. The same bill was introduced in the Senate in July 2014, but never advanced.

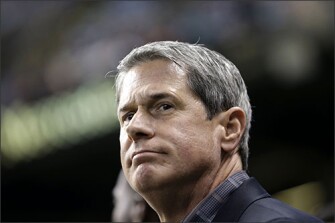

And on Thursday, U.S. Senator David Vitter (R-La.) introduced his “Student Privacy Protection Act.” That bill, which would radically amend FERPA, takes a dramatically different tack than the plethora of other student-data-privacy legislation that has appeared at the federal and state level over the past year. Vitter’s bill would expand the types of student information covered under FERPA, require educational institutions to obtain prior consent from parents before sharing that information with third parties, outlaw a host of data-sharing practices that have become commonplace over the past decade, and require educational agencies and private actors who violate FERPA to pay cash penalties to individual families.

“Parents are right to feel betrayed when schools collect and release information about their kids. This is real, sensitive information —and it doesn’t belong to some bureaucrat in Washington D.C.,” Vitter said in a statement. “We need to make sure that parents and students have complete control over their own information.”

Both bills come on the heels of U.S. Representatives John Kline (R-Minn.) and Bobby Scott (D-Va.) releasing last month a “discussion draft” of a bill that would totally rewrite FERPA. That bill would expand the definition of a student’s “educational record” and ban the use of such information for marketing or advertising. It would also impose new contracting requirements on states and local education agencies and allow for fines of up to $500,000 to be levied on educational service providers that improperly share student information.

And that’s not to mention a White House-backed proposal from U.S. Reps. Luke Messer (R-Ind.) and Jared Polis (D-Colo.) to create an entirely new federal law that would also address student data-privacy.

Got all that?

On its reissue, the Markey-Hatch bill continued to garner a lukewarm reaction. Observers generally seem to agree that it represents a step in the right direction, but doesn’t go nearly as far as is needed to effectively address the challenges of protecting sensitive student information in the digital age.

For example: In an email, Leonie Haimson, the co-chair of the Parent Coalition for Student Privacy, praised the bill for seeking to bar all targeted advertisements to students. But she questioned the strength of the bill’s provisions related to new security requirements for vendors and the redisclosure of student information by third parties, as well as its lack of enforcement mechanisms.

Meanwhile, a host of representatives of conservative and anti-common-core organizations issued statements of support for the Vitter bill.

Privacy advocates and educational data proponents alike, however, seem a little unsure exactly what to make of it.

The bill’s provision requiring educational agencies and institution’s to receive parental consent before sharing student data with third parties would largely flip current practice upside-down.

It would also for the first time allow for individual families to receive cash awards from educational agencies and private actors that violate their children’s FERPA rights—at least $1,000 per child for a first offense, $5,000 per child for a second offense, and $10,000 per child for a third offense.

The bill would seek to stop companies’ use of individual student data to improve their products and services—a carve-out that has been found in most other federal and state data-privacy bills.

It would seek to make sure that FERPA’s protections are properly extended to homeschooled students.

Vitter would prohibit the use of federal funds to support:

- Any kind of “affective computing” that includes analysis of physical or biological characteristics such as facial expressions or brain waves;

- Data obtained through “predictive modeling,” including information based on “predicting or forecasting student outcomes;"

- “Any data (including any resulting from national or State assessments) that measures psychological resources, mindsets, learning strategies, effortful control, attributed, dispositions, social skills, attitudes, intrapersonal resources, or any other type of social, emotional, or psychological parameter.”

And the bill would “gut” statewide longitudinal data systems by prohibiting officials from using student-level data to track students’ postsecondary enrollment and path to the workforce, said Paige Kowalski, the vice president for policy and advocacy for the Washington-based Data Quality Campaign, a nonprofit advocacy group that supports effective use of educational data.

“It’s clear that [Vitter’s] intent is to respond to parents’ concerns, and not respond to the increasing demand from educators, the public, and parents who are demanding better information to make decisions,” Kowalski said.

“His bill does not [recognize] the value of that information.”

Photo: U.S. Sen. David Vitter, R-La., sponsored a new bill that would overhaul FERPA --Jonathan Bachman/AP

See also: