Things have changed. On that, we can all agree. But will they be forever changed, especially regarding the use of technology in K-12 education, once school buildings reopen after the coronavirus pandemic subsides? The answer is just beginning to emerge as school districts begin crafting their strategies for what teaching and learning will look like for the 2020-21 academic year and beyond.

Consider the case of the Joliet public schools, a K-8 district in Illinois.

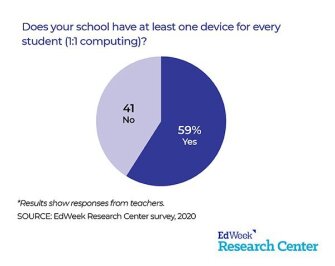

In 2018, it began piloting a 1-to-1 computing program for its 6th graders. Until then, students across the district had been using laptops stored in shared carts that never left the school building.

The plan had been to begin providing the students with devices they could take home and keep until high school, so that within three years, all students in grades 6-8 would have take-home devices. Students felt more ownership of the devices than they did previously because they knew they’d get to keep them through middle school, said Theresa Rouse, the district’s superintendent. “It was a really good plan and it was working really well,” Rouse said.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit. It became crystal clear that many elementary students would need take-home devices during state-mandated school closures. The district’s technology team quickly set to work cleaning, repairing, and updating classroom devices for home use.

That process took almost a month. Now, all students in grades 2-8 have their own devices at home, and the district is hoping to procure even more for youngsters in kindergarten and 1st grade.

Those devices, and the round-the-clock learning they can facilitate, won’t evaporate once the imminent COVID-19 threat has passed. “What will come out of this is an acceleration toward using more and being more confident and competent using digital tools,” said John Armstrong, the district’s director of technology and information services.

A Higher Level of Digital Savvy

Despite widespread frustrations with the downsides of remote teaching and learning, many teachers are seeing how online learning can make it easier to move students in the same class at different paces and provide one-on-one feedback for struggling students, when they’re not all in the same physical space. Plus, students are getting more opportunities for independent, self-directed learning, and the emphasis during COVID-19 has been more on projects and completion than assessments that demonstrate aptitude.

The question is whether those approaches will continue and maybe even expand once school buildings reopen, or whether teachers will revert back to the ways they used technology to teach before school buildings were shut down.

To build more effective ed-tech strategies for the 2020-21 academic year, experts say schools should use five key approaches. They range from looking to early tech adopters for guidance to preparing for a range of scenarios.

- Look to early adopters of technology within your school district or others for guidance on how to proceed.

- Carefully evaluate technology tools to ensure they’re appropriate for classroom use and meet student data-privacy guidelines.

- Survey teachers and families to find out how they are using technology both at home and in school buildings to determine what’s working and what could be improved.

- Think creatively about how remote learning might be applied in your district even when it’s no longer mandatory, such as for extending the school day or offering more summer school learning opportunities.

- Prepare for a range of scenarios for the use of technology next school year, including the possibility of “rolling” unexpected school closures or social-distancing requirements that limit school buildings’ occupancy.

“The net on this is at least, let’s just say everything goes back to normal, we’ve got a lot of teachers that received a lot of training on how to use digital content,” said Antonio Romayor, the chief technology officer for the El Centro Elementary school district in Southern California.

But how much will the traditions that define the American school experience change to accommodate new technology, and a much higher level of teacher tech skills, once the dust settles?

The answer will depend largely on some of the same factors that perpetuated inequities before the coronavirus: access to resources and professional-development opportunities; willingness and capability to experiment; support from federal and state policymakers to rethink long-standing conventions; and a willingness to invest in transformation.

While pondering the future may not be the first priority during an unprecedented crisis, it may be necessary from a technological perspective. Public-health officials have warned of a possible resurgence of COVID-19 cases this fall, and the specter of the virus will loom until a vaccine is widely available. Seventy percent of educators who responded to an EdWeek Research Center survey in early May said they’re already planning for multiple reopening scenarios for the fall.

“It seems prudent, if you’re a district leader, to be planning for the possibility that sometime in school year 2021, or multiple times, you’re going to have to close for one, two, maybe three weeks at a time,” said John Watson, the founder of Evergreen Education Group, a K-12 digital learning research and consulting firm. School leaders who work with Evergreen’s Digital Learning Collaborative have told Watson they’re preparing for “a significant percentage of parents who don’t want to send their kids back to the physical school.”

New PD Approaches Emerge

Brian Toth, the superintendent of Saint Marys Area public schools in Pennsylvania, has long been a proponent of technology as a classroom tool. Until recently, though, he had no way of knowing how many of his district’s 2,000 students would be able to access assignments from home.

That all changed when his team sent a survey at the start of the pandemic, asking every family in the district to share the number of devices and the quality of internet access—if any—in their homes. To his surprise, more than 98 percent of families responded—a marked increase over any similar survey the district had previously sent. “We were very pleased to find out that we had a lot more connectivity in households than we thought we did,” Toth said. In some cases, families with multiple children needed extra devices so their students weren’t competing for them.

Toth sees online learning as an opportunity for students to learn on their own time for any number of reasons, whether they have to care for younger family members or take a part-time job during the day to help cover family expenses, or because they simply prefer doing schoolwork outside typical school hours. One high school principal told him a majority of students have been turning in assignments and answering emails between 10 p.m. and 1 a.m. “If that fits better for kids to do that, what’s wrong with that?” he said.

This fall, regularly scheduled professional development for teachers will for the first time include sessions on online instruction, Toth said. He’s expecting more students to request online options even once the pandemic ends. And he foresees far more virtual staff meetings and education conferences in the future.

“Even those who were scared to death of doing something online, they’re going slow with it and they’re seeing some wins,” Toth said.

Lessons Learned

Teaching remotely has prompted Megan Mullaly, who teaches 6th grade English and social studies at Dartmouth Middle School in San Jose, Calif., to provide more specific feedback to students than she normally would, because students aren’t often hearing from her otherwise. Looking ahead, she envisions continuing to offer “flipped instruction,” in which students complete assigned readings on their own time and then conference with her for discussion, even when it’s no longer required. It takes hard work and practice, though.

Alexandra Griffith, an English teacher at Oshkosh West High School in Wisconsin, has adopted a more personalized approach during remote learning than she has ever used before. Her students are currently writing memoirs. Some grasp the concepts of writing a memoir more easily than others.

In person, Griffith wouldn’t be able to pull aside a single student for extra help without slowing down or neglecting the rest of her students. Now, “if I notice a kid is really struggling to understand one of the concepts that’s necessary for memoir writing, I can stop them from moving on to other assignments” while other students proceed, Griffith said.

She hopes states will begin to relax regulations around seat time and instructional days, shifting instead to focus more on measuring “quality learning that promotes mastery” as evidence of a child’s academic progress.

For a number of reasons, many districts may need to continue offering remote teaching and learning opportunities for some educators and students even if state-mandated closures have lifted. For example, teachers and students who have underlying health conditions, such as asthma, may choose not to return to school buildings until the pandemic has passed.

That is a scenario many districts are eyeing right now. But ongoing remote learning will present challenges for some districts more than others, said Justin Reich, an education researcher and the director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Teaching Systems Lab. Districts that have already identified successful practices this spring will be able to replicate them going forward, but others will have to admit, “Yep, that didn’t work,” he said.

At least a few teachers in almost any school “have the aptitude and the disposition and life circumstances to be able to do a bunch of innovative things right now,” Reich said. Struggling schools with limited resources should look to those early adopters for lessons learned that they might replicate, he said.

Brian Seymour, the director of instructional technology for the Pickerington school district in Ohio, echoed Reich’s concerns about making sure all teachers get the help they need whether they are teaching remotely or in physical classrooms in the fall.

“Those teachers that have embraced the tech training, and all of the different programs and platforms that we have in the regular classroom, have been very successful in a digital classroom,” but others are lagging behind, he said.

‘Educational Technologist’s Dream’

Rick Ferdig, a professor of educational technology at Kent State University, is excited by the potential for the increasing use of technology over the past several months to bring about long-lasting changes in instructional practices.

But he’s also worried that schools will overinvest in new technologies without having a solid instructional plan in place. “I know some really good districts that are doing very well with low amounts of technology because they have a deeper understanding of pedagogically supporting students,” he said.

Still, Ferdig describes the current K-12 landscape as an “educational technologist’s dream.” That is especially the case for schools that have the technology resources available to try new approaches but have not yet had compelling reasons, until now, to do so. He is looking forward to seeing what emerges from that kind of experimentation over the next year.

But many educators are skeptical that the technologies used during closures will transform teaching. In a Consortium for School Networking survey of more than 500 K-12 tech leaders conducted last fall, more than half of respondents said their staff isn’t large enough for helping teachers implement technology. School budgets are likely to tighten further this fall.

Schools will have to get creative. Sal Pascarella, superintendent of Danbury public schools in Connecticut, believes schools have learned important lessons this spring on using online learning to bridge equity gaps, like creating opportunities to extend the school day and opening more remote summer school options.

He sums up what many in education feel: “It certainly has caused us to change in a way that would have taken a longer time to change mindsets had we not had the virus.”