For several months, conversations spoken in Swedish swirled around me wherever I went: song-like, fast-paced, foreign. Thanks to my blonde hair and blue eyes, I looked Swedish, too. Waiters, bus drivers, and cashiers talked to me before I sheepishly asked if they would switch to English instead. Despite that, I was determined to learn their language.

I was living in Sweden for part of the past year, away from my 1st grade classroom in Minnesota. My husband was pursuing a career opportunity at Uppsala University and I was granted a short leave of absence to tag along.

Over eight years, I’ve taught a range of readers, from those who could not recognize the letters of the alphabet to those piecing together the symbolism in a book well above their grade level. I have a master’s degree in children’s literature, co-chair my district’s language arts committee, and even work at a local bookshop.

Considering all of this, surely I could teach myself to read in a new language, right?

I started with the basics. Wandering a Swedish grocery store, I’d easily match words with meaning: mjolk is milk; öst is cheese; kyckling, chicken. Menus were slightly more complex, but I often could figure them out after a bit of trial and error (hello, context clues).

I started noticing words that were similar to English (äpple) and those that were like each other (lök is onion and vitlök is garlic). Finding patterns and looking for ways to remember these new words was a fun challenge. I’d fill my days with Swedish and—if I’m being honest—felt pretty good about my progress.

Eventually, I reached a point where I needed outside support for learning the language. I’d read everything I could find on signs and posters but wanted more. I downloaded a program and got right to work. I was breezing through levels—please, I’d learned how to say “hello” and “goodbye” months ago!—like it was a video game waiting to be mastered. Then, I hit a roadblock.

The program introduced a few letters and pronounced their accompanying sounds. Then, the letters would move about the screen in a random order and I was asked to click the sound I heard. The problem? I couldn’t hear a difference. To my untrained ear, the two sounds were almost identical. I turned up the volume, closed my eyes, replayed the tutorial. Nothing made a difference.

And that is when I knew. I hadn’t been learning the language well at all. I was stuck in the phonemic awareness stage of reading.

Why We Need Literacy Guides

As someone who teaches reading, I know that mastering literacy skills often follows a progression: phonemic awareness (hearing, manipulating, and replicating individual sounds) precedes understanding phonics (matching sounds with letters). Both skills must be solid before students can make strides in fluency, vocabulary, and, ultimately, comprehension. In a balanced literacy approach, we teach skills simultaneously but also understand that if one phase isn’t mastered, the next stage will not have a solid foundation to build on.

My heart sank as I realized I had jumped straight to learning vocabulary. How naïve of me! Surely, I knew better. Yes, I could name and recognize foods from the grocery store, order off a menu, and read posters in the cathedral. But my reading would never progress if I couldn’t hear, let alone replicate, basic differences in Swedish sounds. Realizing that I had to start back at square one, I felt disheartened.

I suppose this is why we don’t explicitly tell students when they’re stuck in a phase of literacy. It feels daunting, impossible. Instead, as teachers, we find new ways to reach our students. We don’t give up.

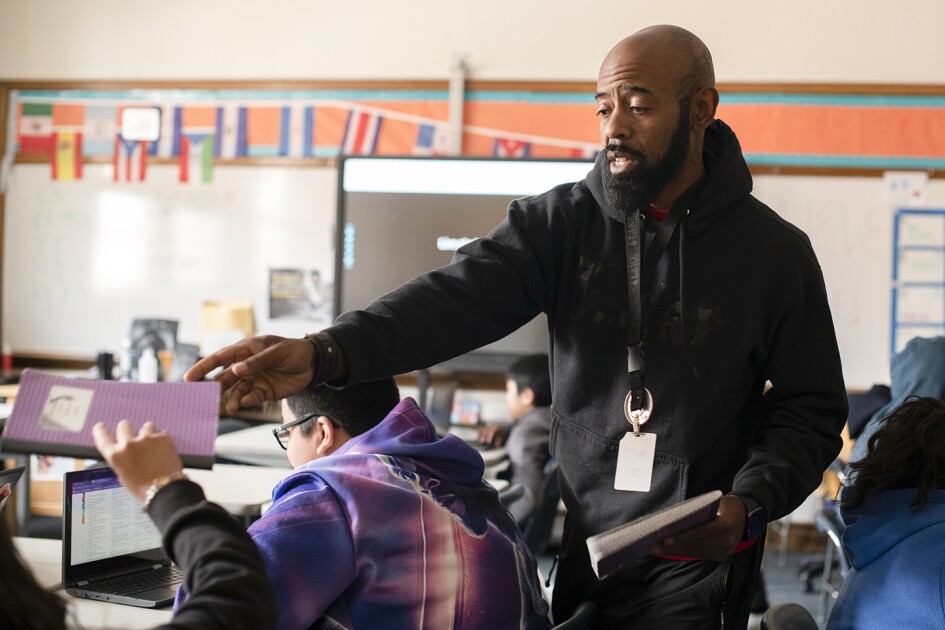

My mind returned to a student last year who was far behind his peers. Hardly able to hold a pencil, he too had difficulty distinguishing different sounds and matching those with their corresponding print. We worked together multiple times every single day. If I found a few spare minutes, I’d pull out a book or alphabet chart and sit with him. With repeated, explicit instruction and practice, he slowly made progress. By the end of the year he was beginning to hear and clap syllables, identify letter names and sounds, and grasp one-to-one correspondence. He was still behind his peers, but on his way toward independent reading.

I realized that’s what I needed: a guide who wouldn’t give up on me. Someone who would repeat the sounds over and over until I began to recognize them on my own. Someone who would make the connections and help me apply what I was learning.

Unfortunately, I didn’t have that someone.

My time in Sweden has since come to a close. Soon, I will be back in my classroom facing 20 eager readers. I’ll bring stories of living in a different country and a long list of books I can’t wait to introduce. I’ll also bring a new perspective and appreciation for the readers who are struggling, the ones who seem stuck in the phonemic awareness stage. I know how it feels, but I also have the skills and drive to keep pushing those readers forward.

I may not be able to fully teach myself a language that is foreign and different, but I can and will teach a language I know well. I will be that literacy guide—that someone—for my own students.