This summer, like many teachers, I put in some long hours reflecting on my teaching practice and looking for ways to improve it. One part of my learning involved reading 21st Century Skills: Learning for Life in Our Times, by Bernie Trilling and Charles Fadel. Both Trilling and Fadel have served on the board of the Partnership for 21st Century Skills, a consortium of companies and organizations promoting a new vision of American education oriented around recent transformations in society and workplaces. As I read the book, I experienced something I often feel when I immerse myself in new ideas in education—the sense that, in my own practice, I’m making progress and falling behind at the same time. Fortunately, one of the authors, Bernie Trilling, happens to be a parent at my school, and I was able to sit with him for a long conversation about the book and how teachers can grow in understanding and integrating 21st-century skills without being overwhelmed by the changes.

First, it is important to recognize that Trilling and Fadel’s book was not written exclusively for teachers. You will not find many reproducible black-line masters to adapt for classroom use. In his conversation with me, Trilling described the book’s intended audience as educators at every level, parents, the business community, and the broader, educated public. Teachers will benefit from the book’s specific examples of 21st-century learning in practice, but should approach the book with the understanding that it is more a conceptual work than a “how-to” manual.

In recent years, Trilling, who is the global director for the Oracle Education Fund, has spoken to many audiences about 21st-century learning. He believes that there is a fairly broad consensus around the general thrust of the concept. That consensus can be seen through a discussion exercise that Trilling likes to use in his presentations. The exercise consists of four questions (paraphrased here) that are also included in the introduction to the book:

• What will the world be like when our students are out of school and well into careers and adulthood?

• What skills will they need to succeed in those careers and as citizens of that world?

• What were the conditions that made possible the most powerful learning experiences in your life?

• What would it look like if we transformed schools and teaching to provide students with an education based on the answers to the first three questions?

When using these questions to start discussions, Trilling says he finds broad agreement among audiences that our students will need to be lifelong learners who are able to reinvent themselves as workers and adapt to accelerated changes in the world. And they will need to be able to think critically and analyze and synthesize information (coming at them in ever-increasing volume) quickly and effectively.

When individuals describe their most positive learning experiences, Trilling says, they usually talk about practical, authentic experiences with open-ended outcomes and real risks of failure. There is a place for academic exercises and examinations, he adds, but ultimately students and adults learn the most from doing important work that has meaning beyond school and allows them to be creative and adaptive.

Turning to the question of what schools and teaching should look like today, Trilling’s interlocutors tend to say we need to create more opportunities for students to work together on real-world problems; to become more adaptable and resourceful; and to prepare for a world in which information is increasingly accessible and unrestrained.

The Big Picture

Thinking about my own practices relative to the book’s core arguments, I can see that I’ve made progress. My students use literature to understand fundamental questions about human experience, history, their nation, and culture. I give them the time and flexibility to investigate these questions, consider some possible answers, and come up with responses of their own. They use a variety of technology platforms to communicate with each other, with me, and with remote sources, and also to organize and present information. And yet, that tension won’t go away—the sense that I need a significant upgrade in skills and resources to ensure that those types of learning experiences are the norm rather than the highlights of my class.

How do I integrate 21st-century learning concepts into my instruction and still operate within the systemic constraints of the classroom, school, district, and state? Given the structures, resources, and baggage of an existing school or system, working towards a new vision of teaching can be intimidating. We often find ourselves engaged in years of debate over a change in the math curriculum or the school schedule. How do we even begin to address larger changes that fundamentally alter the roles of teachers and students?

Trilling recognizes that education is often mired in bureaucracy and politics, but he emphasizes a key point to help educators keep a broader picture in our sights. He argues that the movement towards 21st-century learning in education is actually inevitable—it’s just the way society and businesses are moving. The question is how long the shift will take, and how underserved our students and economy will be if we delay the transition. In a way, that’s a liberating idea—a shift from “if” to “when.” The guiding question for educators and administrators, according to Trilling, becomes “How does this policy or practice help students develop these skills?” When the answer is difficult to determine, the policy or practice needs to be rethought.

Where to Start

Of course, for many teachers, there is also a saturation point, a time when it feels like there’s simply no more room for new ideas, even good ones. Many of us operate in survival mode, where the demands of the job constantly exceed our capacity, and we do the best we can just to manage. So when someone comes along and starts talking about changing the way we do everything, there’s a combination of fatigue, fear, and resistance that can prevent us from embracing the new.

If 21st-century learning were just a matter of technology, that might be manageable. I hope teachers are becoming more comfortable using new technologies in their instructional and professional lives. But technology is only one part of the shift.

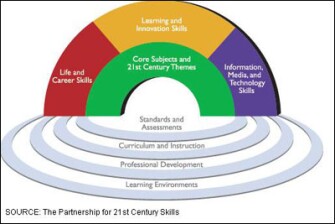

In their book, Trilling and Fadel present a 21st-century learning “Knowledge-and-Skills Rainbow” that, in addition to “Information, Media and Technology Skills,” includes “Life and Career Skills” (e.g., leadership and cross-cultural adaptability), “Learning and Innovation Skills” (e.g., problem-solving and collaboration), and core subject knowledge. The challenge then is not simply to integrate the latest technology into classrooms, but to help students develop intellectual habits that prepare them for a future in which almost everything is more accessible, complex, global, flexible, and fast-moving.

I asked Trilling if he had some advice for teachers about how to start if the whole prospect of 21st-century skills seems overwhelming. His answer did not involve technology, and wouldn’t necessarily cost anything. Try one project, he suggested, one long-term activity where students work together to create a response to a complex and real problem.

And there was one last piece of advice Trilling offered that I agree with wholeheartedly: Teachers must do a better job of publicly advocating for change. Our students are capable of greatness, and they deserve a school system that has the priorities and resources to prepare them for the future. The best way to motivate communities to support education improvement is to make sure people see the good work we’re doing and understand how much better off the whole community will be if schools, like the rest of society, evolve from an industrial model to one that is reflective of the times in which we live.