In the early 1990s, two business experts set out to design a new way to track corporate performance by looking not just at bottom lines such as profits and share prices, but at all the operations they felt were essential to achieving long-term success.

Today, their invention is catching on in education. Called the Balanced Scorecard, it is being used in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg, N.C., and Richmond, Va., districts, many Georgia school systems have implemented it, and state leaders elsewhere are showing interest.

The scorecard is a kind of report card for a district or a school. Along with test scores, however, it includes data on factors that can affect student performance, such as teacher training, parental involvement, and the frequency with which school buses are on time.

Many district leaders who use the scorecards call them a powerful management tool. Deciding what to put on a scorecard forces a conversation about how all parts of a system fit into its overall objectives, and about how to measure whether each part is achieving its aims.

Michael Vanairsdale, a former superintendent of the Fulton County, Ga., public schools, said he knew the approach had changed mind-sets in the 86,600-student system when maintenance crews started scheduling their work so as to minimize the disruption to instruction.

“It focuses improvement efforts, and I don’t think we’ve had a tool that does that before,” said Mr. Vanairsdale, who now teaches balanced scorecards to districts through Georgia’s Leadership Institute for School Improvement, a quasipublic training center in Atlanta.

Not Quick Fixes

As simple as they sound, the scorecards take time. Often, they mean creating surveys of parent, teacher, and student perceptions, which may be given more than once during the year. Another difficulty is setting realistic but challenging targets for each measure.

But fans say it’s worth the effort to bring more attention to the “inputs” that lead to improvement—called “leading indicators.” Accountability based solely on outcomes, they contend, can lead to quick fixes that wind up hindering long-term progress.

That was exactly the concern of the Balanced Scorecard’s creators, Robert S. Kaplan, a professor at Harvard University’s business school, and David P. Norton, a business consultant. Traditional corporate performance reports, they believed, encouraged shortsighted management by not stressing what created value.

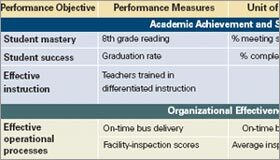

A sampling of the indicators on the balanced scorecard of Georgia’s Monroe County school district shows a mix of student results and factors that can affect them.

*Click image to see the full chart.

SOURCE: Monroe County, Ga., Public Schools

“If you’re going to be measured on quarterly financial performance, you cut back on training employees, you don’t maintain equipment, you don’t invest in new products, and you don’t pay attention when customers are unhappy,” Mr. Kaplan said.

Their answer, which they came up with by working with 12 companies, is to balance financial figures with data on three other areas of performance: customer satisfaction, internal business operations, and the ability to continuously improve through innovation.

For each, the scorecard includes quantifiable measures. So if quality is a key objective, it might show the percentage of defects reported, and how that has changed over time. A measure of innovation might be how long it takes to launch new products.

To see how the equation looks in education, take the 3,800-student Monroe County, Ga., district, where Superintendent Scott Cowart adopted a scorecard four years ago. Along with student results, it includes data on organizational effectiveness and community support.

Examples include the turnover rate among staff members, the difference between the district’s budget and expenses, and the number of teachers who have been trained in new strategies. Other indicators are survey results on the perception of central-office support and of school safety.

Like many districts that use scorecards, Monroe County has one for each school with similar indicators, and they’re displayed prominently in the buildings. When its administrators give school board reports, they often get pressed about data in the scorecards.

“What we have done is create a line of sight, such that every person in the organization can see from what they do to the system’s strategic objectives,” said Mr. Cowart. “It’s a measurement tool, but more importantly, it’s a planning tool, and a communication tool.”

Proponents of balanced scorecards say what makes them effective is what happens before and after they’re instituted. Many districts start by updating their school improvement plans, and then figuring out how to break them down into measurable goals.

Once a scorecard is in use, many practitioners say, the aim is not to reward or punish based on such data, but to force employees to think about how to address weak spots that may be affecting student results by emphasizing the connections.

At Claxton Middle School in the 1,900-student Evans County, Ga., district, the scorecard includes homework-completion rates. The percentage is calculated by regular reports from teachers on how many students are turning in assignments.

“It has led us to have conversations to say, ‘What can we do to make sure their homework gets done?’ ” said Principal Diane Holland. That, she added, has encouraged staff members to more often urge students who arrive early to use the time to finish their homework.

Balanced scorecards even are used to change the behavior of school boards. In some districts, the boards not only adopt a balanced scorecard for the district, but require that new agenda items brought to the panel be linked to one of its goals.

George Braxton who chairs the school board of Virgina’s 26,000-student Richmond district, said having such a policy has helped align a board that used to get mired in minutiae. He said candidates for board seats now cite the scorecard in their stump speeches.

“Once you agree to working on certain measures, and list certain things as priorities, it forces a focus,” he said. “And for those who aren’t on the same page, it sort of leaves them out there, because everyone else is moving toward getting those things accomplished.”

True, there can be problems. Some district leaders say scorecards can be viewed the wrong way. Since the aim is to set challenging targets for each indicator, one showing that all targets have been met isn’t a good thing. Nor is having some unmet targets necessarily bad.

Wider Use

Georgia’s Leadership Institute for School Improvement estimates nearly one-quarter of the state’s 180 school districts use balanced scorecards in some way.

States are taking notice. Education department leaders in Delaware and Indiana are getting trained on balanced scorecards through a program run jointly by the business and education schools at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

In Indiana, the state school board plans to create a scorecard for itself, said Jeff Zaring, the chief of staff at the Indiana Department of Education. Recently, the board began drafting objectives, such as communicating a sense of urgency about improving schools.

“Our state board has the responsibility of setting the educational goals for the state, and this is the mechanism that we’re using to do that,” said Mr. Zaring. The board will hone its goals, and come up with indicators linked to them, in the coming months, he said.

Valerie Woodruff, the Delaware secretary of education, said she wants balanced scorecards to be part of the process districts use to apply for state money. She said she’d like to have all school systems start with a common set of indicators, which they could adjust and add to.

The University of Virginia-run training that both states are taking part in is part of a larger leadership-development program funded by the New York City-based Wallace Foundation, which also underwrites coverage of leadership in Education Week.

Leading the training on balanced scorecards for the university is James Pughsley, a former superintendent of North Carolina’s 129,000-student Charlotte-Mecklenburg schools, one of the first districts to use the tool. He said he’s not surprised to see it catch on.

“Most organizations come up with a vision statement, mission, or that sort of thing, but they get caught up with that, and don’t know how to put it into place,” he said. “This translates that into goals and objectives so that people can see the same picture.”