A recent decision by the New Hampshire board of education to place a moratorium on new charter schools drew an angry response from elected officials and parents—and underscored recurrent tensions among state and local officials across the country about how to fund those schools and manage their growth.

As of last week, state legislators and board members in New Hampshire said they were confident that they could reach an agreement to lift the hold on charters, which was put in place Sept. 19. But that optimism was also tempered by the board’s questions about the state’s longer-term plans for funding charter school growth.

Concerns about charter school oversight, amid rising enrollment, also were raised recently in a very different educational setting: the Los Angeles Unified School District, where a school board member recommended postponing the review of new charter school applications, pending a number of policy changes.

The concerns raised in New Hampshire, while specific to that state, have emerged in various forms elsewhere, as charters expand and occupy an increasing share of the public school market, said Robin Lake, the director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, at the University of Washington.

“The financial question has always been central to the charter school debate,” said Ms. Lake, adding that charters’ continued growth will require policymakers concerned about funding and oversight to “sit down with charter schools and work out solutions.”

Growth Pressures

Forty-one states allow charter schools, and one of the nine that does not, Washington, will allow voters to decide Nov. 6 on whether that policy should be changed. Over time, the trend has been for states to remove restrictions on charter school growth.

A decade ago, 23 states, plus the District of Columbia, had caps either on the number of charter schools that could open per year, or overall, according to the Center for Education Reform, a Washington-based organization that supports those schools. Just 14 states have those types of caps today.

Outright moratoriums on charter schools are rare. In most of the handful of states where they have been implemented, those policies were approved by legislatures where there was political resistance to charters, and as support for charters grew, those bans did not stay on the books for long, said Todd Ziebarth, the vice president for state advocacy and support at the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, in Washington.

New Hampshire lawmakers previously had approved a moratorium on new charters, which lasted from 2007 to 2010, at which point legislators nixed it as they prepared to compete for federal Race to the Top funding. That federal competition discouraged state-imposed limits on charters.

The state’s most recent moratorium came about last month. Board members voted unanimously to take that step after arguing that state legislators had not provided funding to cover the costs of eight charter schools approved over the previous two years, leaving a $5 million shortfall. New Hampshire currently has 17 state-approved charter schools, and there are 15 at some stage of seeking approval to open.

In a letter explaining the decision, board Chairman Tom Raffio said the panel “continues to be supportive of charter schools,” but said it would be inappropriate to clear more of them to open, without additional funding.

The action by the nonpartisan, appointed state board disappointed Karin Cevasco, a parent who began work last year planning to open a charter in Nashua that would integrate arts across the curriculum.

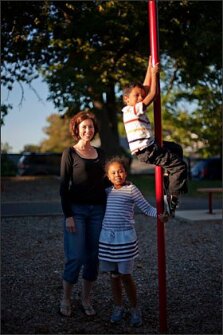

The process for securing approval from the state board already had been a laborious one, and the moratorium only added to the uncertainty, she said. Not having state approval has made it difficult to secure property for the school, said Ms. Cevasco, who hopes to send her two children to the new charter. The possibility of the moratorium lifting buoyed her spirits somewhat, she said, but supporters of the proposed Gate City Charter School for the Arts still have a lot of work to do to open by next fall, as they envision.

“We’ve worked for a year and a half” on the project, Ms. Cevasco said. “We’re doing what we can to prepare for the opening of the school. ... We’re confident in our model.”

The board’s move also drew sharp criticism from the New Hampshire Center for Innovative Schools, which said the board and the state’s department of education could have avoided the shortfall by giving state lawmakers more accurate projections about charter school growth.

“The rationale and logic on this was terrible,” said Matt Southerton, the director of the Concord-based group.

But Mr. Raffio said that while coordination between the department and legislators could have been better, projecting future school enrollment, and the costs of individual charters, is difficult.

Seeking a Solution

As of last week, Mr. Raffio and state Rep. Kenneth Weyler, Republican chairman of the House Finance Committee, both said in interviews that they were confident that the state could end the impasse and find the charter school funding to address the state board’s immediate concerns.

Mr. Weyler also chairs the legislature’s joint fiscal committee, which he said has the power under state law to shift funding within the state’s budget without a full act of the legislature—and thus could move the $5 million to meet charter school costs. The committee is likely to take that step at a meeting late this month, he said.

Mr. Raffio said he will recommend that the board of education wait until after the fiscal committee votes to move the money before his panel takes action, probably in November.

“The proof is going to be in the pudding,” Mr. Raffio said. Legislators “all seem super-confident” that the funding will be provided, he said. “If they’re that confident, all I’m looking for is that they codify that.”

Mr. Raffio added that he hoped the fiscal committee would go a step further and provide some guarantee that the costs of future charter school growth would also be covered, so the issue doesn’t emerge again. He said he was not sure what the board would do if state lawmakers don’t agree to take that step.

State Variations

New Hampshire’s overall approach to funding charters does not make it easy to accommodate growth and shifts in demand for those schools, argued Mr. Ziebarth of the national charter alliance. In many states, money for charters is rolled into the state’s overall school funding formula, which allows for money to be reallocated between charter schools and regular public schools based on need.

In New Hampshire, charter schools are funded as a separate line item, which requires state officials to make projections about enrollment.

In Los Angeles, questions about a school system’s capacity to cope with charter school growth, while also ensuring they are adequately regulated, emerged last month, when district board member Steve Zimmer proposed a resolution calling for the system to hold off reviewing new charter school applications for the time being.

Mr. Zimmer, whose resolution is scheduled to be heard by the board Oct. 9, raised concerns about several issues, including charters serving a relatively small portion of students with moderate to severe disabilities—a long-standing concern in the district—and the lack of consistent reporting from those schools on issues such as disciplinary policy, parent engagement, and closing achievement gaps.

The board member says he is a charter school supporter. But he questioned whether the district has the capacity to monitor the quality of a charter system that now enrolls 110,000 students. He said that the board often gives scant reviews to charter applications before approving them.

“We have to make sure we’re providing a baseline of oversight in what’s become a radically deregulated environment,” Mr. Zimmer said. The district needs to begin a process for “completely overhauling how we consider charter applications,” he said, one that will ensure that for parents weighing school options, “every choice is a quality choice.”

That proposal has drawn the objections of the California Charter Schools Association, which has called for crackdowns on low-performing charters but believes the independent schools in the district’s 664,000-student system are put through extensive review by district staff, said Jed Wallace, the group’s president.

The resolution is “a solution in search of a problem,” Mr. Wallace said. “The portfolio of schools in Los Angeles are performing very well.”