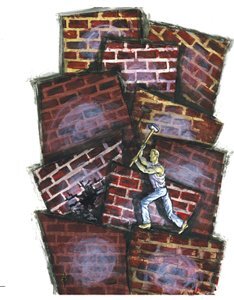

It’s easy to see why people might feel that education policy has hit the wall. The federal No Child Left Behind Act is neither reauthorized nor reformed. Growing numbers of schools are reported as “failing.” The despair about high school seems universal. Education is essentially absent from the 2008 presidential debates. Few governors clamor to be an “education governor.”

This causes people to question strategy, to ask: Are the system reforms failing? With standards and accountability, why is performance so flat? Are charter schools fulfilling their promise? Why, as the Manhattan Institute senior fellow Sol Stern asked recently, is choice not showing better results?

System reforms are not failing. It is simply becoming clear that, while critically important, they do not and cannot themselves directly improve achievement. Kids don’t learn from standards, from accountability, from choice, or from charters. It is an error to connect learning to changes in the “architecture” of K-12. Someone could as easily compare scores in one-story vs. two-story buildings. What would that mean? Kids don’t learn from structures. They learn from what they read, see, hear, and do. For achievement to improve, school and schooling have to improve.

The system reforms make that improvement increasingly necessary; they also make change increasingly possible. But they are only half the strategy. To meet its goals, this country must next undertake a serious effort to develop new forms of school and schooling. It is time to redirect K-12 policy toward innovation. In this undertaking, five truths seem important to consider:

1. With attention fixed on system reform, we have not been moving significantly to change traditional school and schooling.

Most of what passes for change and improvement is “inside the box”—marginal changes that look for what works within conventional givens. Some advocates of system reform do not want to change traditional school. Some reforms, as implemented, have in fact strengthened traditional schooling. The general public is comfortable with this. We see the traditional school pictured everywhere: a classroom, kids at desks or tables, a teacher in front of a blackboard. Even one Microsoft ad plugging computers shows kids and desks and blackboard, with no computer in sight.

It is an error to connect learning to changes in the “architecture” of K-12. ... Kids don’t learn from structures. They learn from what they read, see, hear, and do.

People in curriculum and instruction have been writing, speaking, and consulting about different and better ways for children to learn. But they find it hard to get their ideas adopted. As one person visualizes it, the process is like sitting in a crowded waiting room where everyone has a black box on his or her knees. Each waits for the door to open to be able to tell the people who run the system how much better kids will learn “if you would use my black box.” In this vision, though, cobwebs grow; dust settles. The door does not open.

Some argue that school does not need to change; they say we need students to work harder, teachers to teach better, principals to lead and manage better, and they want traditional school to be more rigorous. But trying harder with the traditional model will not do the job. It is time to be open to new conceptions of school and different approaches to learning.

2. Traditional school was not designed for the job that now has to be done; it cannot ensure that all students will learn.

Traditional school never did graduate all its students. Nor did it ever educate all students well. That was tolerable when its assignment was to provide opportunity and expand access. Now the assignment is switched, to “achievement.” Will all students be able to learn to high standards in the traditional model—one built on the notion of “delivering education” and the technology of instruction by a teacher—simply because we tell schools they have to? Motivation is the issue. If achievement is imperative, then effort is essential; and if effort is essential, then motivation must be central. Conventional school is designed almost to suppress motivation.

At the secondary level, conventional schooling’s course-and-class model is a bus rolling down the highway, moving too fast for some and too slow for others. A teacher points out important markers along the way, but students cannot get off to explore what they find interesting: The bus has to stay on schedule. Most high schools are large. A teacher might see 150 students a day, which makes close relationships between teachers and students, and among students, difficult. For motivation, relationships matter.

It would be a risk to bet everything on traditional school’s succeeding. And it’s not a necessary risk, since we could simultaneously be trying different models. So to be taking that risk with other people’s children is unacceptable.

3. Different and high-potential models of schooling keyed on motivating students and teachers clearly are now possible.

If high school is obsolete, the logical response to that obsolescence is innovation. New forms of secondary schooling are both necessary and possible. Already, innovators are developing alternatives to the “batch processing” of traditional school, with students individualizing their work, learning increasingly from projects, taking courses online, and using digital media to do research. The revolution in the storage and manipulation of information has enormous potential to change the paradigm of schooling from one of teaching to one of learning, increasing motivation by capitalizing on the interest and considerable skills of young people in using these technologies. Teachers’ work can be upgraded to planning, advising, evaluating.

Teachers and students are the workers on the job of learning. Deborah Wadsworth, the former head of Public Agenda, was fond of quoting Daniel Yankelovich as saying, “There is an additional level of effort workers can give you if they want to. The challenge is to elicit that ‘discretionary effort.’ ” Maximizing student and teacher motivation could pay off not only in higher achievement, but also by improving the economics of K-12. A professional model might elicit the effort from teachers that the bureaucratic, boss-worker model of school cannot. And whatever we get from students, in the form of increased effort and engagement, comes for free.

4. Radical changes in school and schooling can come into K-12 if we are practical about the process of change.

In most sectors, change begins as a new model appears. “Early adopters” pick it up quickly. Most do not, since the early models often are not very good. (Early cellphones, for instance, resembled a brick.) Rapidly, quality improves and, for a while, the old and new run along together, with people gradually shifting. Over time, tractors replace horses; airlines replace passenger trains; computers replace typewriters.

If achievement is imperative, then effort is essential; and if effort is essential, then motivation must be central. Conventional school is designed almost to suppress motivation.

It has not been like this in education. Suggest changing school and you’ll hear “Not everyone agrees with that” and “That would not work everywhere.” The assumption that change is to be imposed universally and politically, and so requires consensus, is pervasive—and powerful. That is why little changes, and what does change does not change quickly.

We could take the nonpolitical route to change; we could let different forms of school and schooling be adopted by those who want them, assuring others who prefer traditional school that the “different” will not be imposed on them, and having them in turn agree not to suppress the innovative. Over time, schooling, and the institution of school, would change faster and with less controversy. Though some might dislike having differing models in use, diversity is appropriate as well as practical: Young people do differ in their interests, motivations, aptitudes, and backgrounds.

5. New schooling will require rethinking the concept of “being educated,” and of what needs to be learned and how to assess it.

The traditional concept of education as the mastery of subject-matter content is deeply rooted. But a changing world requires some adjustment of our notions about “what students should know and be able to do.” Clearly, children should learn how to read well. There should be standards. Performance will require assessment. But for the 21st century, we might also need skills such as those measured by the Program for International Student Assessment, or PISA: the ability to think critically and creatively, to communicate well, to work collaboratively in teams, and to know how to learn.

Twenty years ago, the public-utility framework of K-12 schooling offered no real opportunity for innovation. Today it does. The unbundling of public education in most states makes it possible to create wholly new schools. States should enlarge and improve this opportunity. Schools can be created by districts, as well as in the open marketplace of ideas. Boston, Chicago, Baltimore, Los Angeles, and other cities are moving ahead with new-schools programs. These schools are the place for innovation to occur. Foundations and the federal government should help with financing. Above all, they should help by affirming that “different” is legitimate.

Innovation, and the strategy of change through gradual replacement, will make K-12 education at last a self-improving institution. Lacking internal change dynamics, education has depended on others, outside, to push improvement into districts and schools. Over the long term, that way of doing things cannot be sustained. The country has too much to accomplish. Public education must be enabled to change and improve on its own initiative, in its own interest, and from its own resources.