Years ago at a conference where funders, tech entrepreneurs, and academics were furiously brainstorming ways for educators to fix schools, a teacher’s voice cut through the cacophony: “With all that is asked of teachers already, where do you propose that we find the time for your pet projects? If you want us to listen, please show us ideas that simplify our lives.” That complaint is as true for the education field today as it was then.

Currently, leaders of social-emotional-learning and character education programs are making big demands on educators’ time and attention. They argue that schools must help students cultivate aspirations, belonging, curiosity, decency, engagement, flexible thinking, grit, happiness, intrinsic interest, and so on. Meanwhile, teachers must try desperately to squeeze 365 days of academic content into 180-day school years.

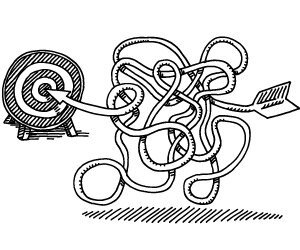

Yet these SEL capacities remain vital attributes to cultivate in our youths. Herein lies the crux of the problem: Social-emotional learning represents crucial skills and dispositions, but we already ask too much from our teachers. So how can we simplify their lives, without oversimplifying these complex ideas?

We might start by distilling social-emotional learning. If we separated the nice-to-know domains from those that teachers must know deeply, wouldn’t we be left with those capacities that are truly fundamental for students’ academic success and personal well-being? I propose, therefore, that we focus primarily on students’ social connectedness, motivation, and self-regulation.

That approach makes sense. Students cannot learn if they hate their teacher or fear ridicule from their classmates. Without motivation, they have no goals to pursue, nor energy with which to pursue them. Furthermore, for learning to occur, they must select learning strategies, focus their attention, and stick to their goals. In short, social connectedness, motivation, and self-regulation are prerequisites for learning—not to mention a host of other desired school outcomes.

Research reinforces the logic of focusing on that triad. Psychologists increasingly appreciate the importance of social relationships for human functioning. Many scientists hypothesize that a portion of our brains evolved expressly to connect with others. This extra gray matter can pay big dividends in schools. Studies on thousands of students show that learners who are better socially connected to their teachers and classmates are significantly more engaged and achieve better than their less well-connected peers.

Of course, bonding with teachers and classmates, by itself, does not ensure learning—motivation is equally important. Simple motivational strategies—such as giving choices on homework assignments—can improve feelings of competence as well as actual competency on exams. Convincing students of the value of the content in question should augment their motivation further. The motivational climate and the types of goals that teachers promote in the classroom are no less important.

We already ask too much from our teachers. So how can we simplify their lives, without oversimplifying these complex ideas?"

Better self-regulation in students, including self-control, emotion regulation, and the adoption of effective learning strategies, typically results in youths who are likely to achieve higher grades, test scores, and graduation rates. Arguably even more important than those schooling outcomes, self-regulation is critical to life outcomes including health, wealth, and public safety.

Beyond logical arguments and robust research, this simplification of social-emotional learning would improve teaching and learning.

By drilling down to students’ three core needs, teachers are armed with a powerful troubleshooting diagnostic. If a student is not learning, her teacher can ask: How healthy are her social relationships? What goals is she pursuing? What are her self-regulatory strengths and weaknesses?

However, distilling SEL to its core components provides more than a diagnostic tool. Research increasingly suggests that even modest interventions in these domains may yield big improvements in student outcomes. In many ways, these areas represent low-hanging fruit for improving student outcomes.

This less-is-more approach allows teachers to diagnose problems and strategize solutions. My own teaching career exemplifies why this deep knowledge is so important. Each semester I assigned my 10th graders an essay on any topic from the course—my teacher-preparation program had alerted me to the motivational benefits of choice. Both semesters, a student named Molly showed up after school begging me to pick the topic for her. Each time, she walked away from our argument frustrated and despairing. Only years later in graduate school did I understand the key nuance that undermined my motivational strategy.

Nearly two decades ago, a now-famous study found that when both offering jam to shoppers at high-end grocers and when suggesting essay topics to undergraduates, participants reacted better to having fewer choices. A large body of subsequent research has reinforced that surprising conclusion: Choice is highly motivating, but only if the choices are limited and meaningful to the chooser. I had paralyzed Molly with too much of a good thing.

The social-emotional-learning movement has identified a universe of important capacities to develop in students. In one way or another, most of these capacities address students’ fundamental needs for social relationships, motivation, or self-regulation. The sooner SEL leaders can narrow the choices they promote to educators and simplify teachers lives, the sooner teachers might listen.