Educators in Nevada seem to agree the state could do a lot more to improve the academic achievement of the roughly 400,000 public school students in pre-K-12th grade this year, who, on average, lag behind their peers in most other states on national standardized tests and graduation rates.

| CASE STUDIES | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| COMMENTARY | ||||||

| Table of Contents |

But improving academic performance is especially challenging in the Silver State, where the number of public school students increased by more than 50 percent between 1994 and 2003, making Nevada’s the fastest-growing K-12 enrollment in the nation.

Many education experts here add that raising test scores and graduation rates is complicated by the high number of new students from immigrant families who need intensive help in English. The number of Hispanic students grew by 214 percent between the 1993-94 and 2002-03 school years, from 14.3 percent of K-12 enrollment to 28.7 percent.

But scores for Nevada’s non-Hispanic white and nonpoor students also, on average, lagged behind those of their peers nationally.

School administrators and teachers here say that schools haven’t received enough money to handle the enrollment growth. Yet state legislators counter that they can’t increase education spending until schools show that the aid they already have is translating into good results.

Keith W. Rheault, the state superintendent of public instruction for Nevada, says the superintendents of the state’s 17 school districts have gotten more organized in the last two legislative sessions about what they seek from the legislature, and lawmakers have approved initiatives that everyone hopes will ultimately improve achievement. “Prior to that, it was every district for himself. We probably had 200 education bills earmarked for different needs,” he says. “The last two sessions, they’ve agreed: Here’s what it takes to improve education in Nevada.”

During the 2005 legislative session, Nevada lawmakers for the first time approved money for full-day kindergarten: $22 million for a statewide pilot program and $7.2 million to pay for portable classrooms to house the extra kindergarten classes. They also provided $92 million that districts can apply for as grants to carry out school improvement plans.

What’s more, the legislature commissioned a study of whether the state’s school aid system adequately finances elementary and secondary education.

“We’re going to, for the first time in decades, take a look at the structure for funding in the state of Nevada,” says Bonnie Parnell, the Democrat who chairs the education committee of the Assembly, the legislature’s lower chamber. “As one district administrator said, ‘We got a lot of icing this last session, but we’re not sure of the foundation of the cake.’”

Achievement Gaps

Nevada came late to the academic-accountability movement that has swept the nation.

In 1997, the legislature passed the Nevada Education Reform Act, which legislators believe has helped the state get on the right track. The law created the Council to Establish Academic Standards in Education, which writes the state standards for student learning, and the Commission on Professional Standards on Education, which works to improve teacher-preparation programs at colleges and universities.

| Vital Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Public schools | 545 (2003-04) |

| Public school teachers | 20,234 (2003-04) |

| Pre-K-12 students | 385,401 (2003-04) |

| Annual pre-K-12 expenditures | $2.3 billion (2002-03) |

| Minority students | 49.2% (2003-04) |

| Children in poverty | 19% (2001) |

| Students with disabilities | 11.7% (2003-04) |

| English-language learners | 18.1% (2003-04) |

Nevada’s performance on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, though, continues to be lackluster. In 2005, the state scored significantly lower than the national averages for all students in mathematics and reading in 4th and 8th grades.

On some NAEP achievement measures, the state is moving backward. For example, from 1998 to 2005, Nevada’s 8th grade reading scores declined by 4.9 points, while the national average held steady. Reading scores for the state’s white 8th graders dropped by 3.2 points, as the national average showed no substantial change.

As is true in many states, Nevada’s scores on the 2005 NAEP show large achievement gaps between black and white students, and between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites. Large gaps also exist between students from low-income families and students from affluent families.

And the state continues to struggle with a low graduation rate. In 2001-02, 55.4 percent of Nevada students graduated with regular diplomas after spending four years in high school, compared with 69.4 percent, on average, nationwide.

Rheault says that the federal No Child Left Behind Act has helped make educators in the state more aware of which students need the most help: English-language learners, Hispanics, and African-Americans. “We need to focus on those and figure out what systems we need to close the gap,” he says.

According to Quality Counts 2006, Nevada ranks 49th among the states and the District of Columbia in adjusted per-pupil spending. Most observers say that with fiscal conservatives controlling the legislature, they don’t expect the amount of aid to schools to increase dramatically soon.

“I think we’ve put a lot of money in education,” says Mike Hillerby, the chief of staff for Gov. Kenny Guinn, a Republican. “It’s fair to ask the questions, ‘What exactly are you going to spend more money on? … When are you going to show that things are getting better?’ ”

Student achievement has suffered because the state takes too fragmented an approach to education, says a researcher at WestEd, an independent research firm that conducted a study of education policy in Nevada last summer.

“We think there needs to be clear direction about what the state needs for education and what it wants—and then decide what the money should be used for,” says Paul H. Koehler, the director of the San Francisco-based firm’s policy center.

In the meantime, WestEd has identified ways that Nevada could improve the achievement and graduation rates of public school students.

Among its recommendations, WestEd suggests that the state use data to drive and evaluate improvement, focus on early-childhood education, and put together a comprehensive system for preparing teachers and providing them with professional development, with a focus on strategies for teaching students who are still learning English.

According to data collected by the Editorial Projects in Education Research Center for the 2004-05 school year, 71 percent of the core academic classes in Nevada were taught by “highly qualified” teachers, as defined by the state under the federal NCLB law, and 65 percent of the core academic classes in high-poverty schools were taught by highly qualified teachers. Both percentages are well below what most other states reported. Researchers note, however, that the state-reported numbers should be interpreted with caution, as there is no uniform way of collecting the data.

And while the median pupil-teacher ratio in Nevada elementary schools is near the national average, schools in the state tend to be larger. For example, 14 percent of Nevada middle school students attended schools in 2003-04 with 800 or fewer students compared with 51 percent nationwide.

Agustin A. Orci, the superintendent for business operations for the Clark County school district, which includes Las Vegas, agrees with WestEd’s recommendations. He says the district has begun to carry out some of them, though it needs more money to make comprehensive improvements.

“As long as we continue to Band-Aid the financial aspects, it’s doubtful we’re going to get extraordinary results,” he says. “You get what you pay for.”

Pay Problems

The 287,000-student Clark County school system receives most of the state’s newcomers—or about 15,000 new students a year. Clark County educates 70 percent of Nevada students, so any dramatic improvement in achievement will have to start here.

A majority of newcomers to the district and this flashy city in the desert are from immigrant families. Twenty-two percent of the district’s students are English-language learners.

To keep up with the growth, the school system builds, on average, one new school per month. Construction is financed entirely through local bonds because Nevada does not provide state aid for school construction.

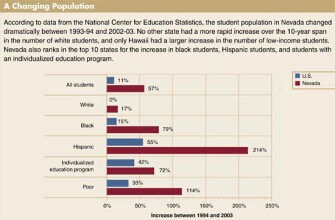

According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, the student population in Nevada changed dramatically between 1993-94 and 2002-03. No other state had a more rapid increase over the 10-year span in the number of white students, and only Hawaii had a larger increase in the number of low-income students. Nevada also ranks in the top 10 states for the increase in black students, Hispanic students, and students with an individualized education program.

SOURCE: Editorial Projects in Education Research Center, 2006

Liliam Lujan Hickey Elementary School in northeast Las Vegas is one of 11 new schools that opened this past fall. Of the school’s 786 students, about 400 are Hispanic. Of those, 278 students have been identified as English-language learners.

On a sunny fall day, Wanda J. Keith, the facilitator for English-language learners at the school, works for 45 minutes with two 5th graders who moved here from Mexico after the start of the school year. She uses a picture dictionary, which labels ordinary objects in English, to gauge how much English the boys know.

One of the boys can read only a few words in English without prompting from Keith, while the other boy can read quite a few isolated words.

“These boys will be fine,” Keith says, after noticing the boys are able to transfer their phonetic skills in Spanish to English.

David L. Harcourt, the principal of Hickey Elementary, hopes the teacher is right. He worries, though, that they still have a lot of work to do to catch up with the expectation that they can do well on standardized tests. “How are they going to do on the [Iowa Tests of Basic Skills]?” he says.

Harcourt believes the state could best help educators address student enrollment growth by reducing class sizes in the intermediate and high school grades and increasing teachers’ salaries, which he doesn’t think are competitive with salaries in other states. In Clark County, a new teacher without any experience starts at $30,468 a year, and the most any teacher in the system can make is $59,431.

Harcourt took several trips to Indiana this year to recruit teachers, but in the end didn’t persuade anyone there to come to the school.

Jerri Mausbach, the principal of Tony Alamo Elementary School, in southwest Las Vegas, has seen her school’s enrollment grow more than 2½ times since her school opened in the 2003-04 school year, from 550 to 1,430 pupils. Nearly 20 percent of the students are English-language learners.

Mausbach says the state needs to provide more money to increase teachers’ salaries and to hire more teachers so class sizes can be reduced. The legislature passed a law in 1989 limiting class size in 1st through 3rd grades, but not in any other grades. So while 2nd grade teacher Tricia A. Hall had 17 pupils at the start of this school year, 5th grade teacher Jennifer Dean had 43.

Lack of Basic Skills

Everyone agrees that recruiting high-quality teachers is one of Nevada’s biggest challenges. Of Clark County’s 11,000 teachers in core subjects, about 8,400 met the state’s definition for being “highly qualified” under the No Child Left Behind Act as of November.

Fewer 4th grade students in Nevada performed at the “proficient” level or above compared with their peers nationwide on the 2005 National Assessment of Educational Progress reading exam. A similar pattern was found when examining performance at the “basic” level or above.

SOURCE: Editorial Projects in Education Research Center, 2006

But attracting and keeping new teachers is made more difficult by the recent skyrocketing costs of real estate. “We had more problems with retention this year than ever before, because housing doubled in price in the last two years,” says George Ann Rice, the associate superintendent for the human resources division of the Clark County schools. The district hired 2,000 new teachers at the start of the school year, and was still short 300 teachers by November.

Rice notes that her district has little say in how its teachers are prepared because 70 percent of them come from outside Nevada. When Clark County can’t find enough certified teachers, it hires long-term substitutes.

Michele Gibbons, the specialist for English-language learners at Rancho High School in Las Vegas, says that three of the 12 teachers at her school who teach classes for such students are long-term substitutes. Of the nine permanent teachers assigned to English-language learners, only two have formal certification in that field, she says.

About one-third of Rancho High’s 3,200 students are English-language learners.

The school has not met the federal No Child’s Left Behind Act’s requirements for adequate yearly progress for two consecutive years, and it has a low graduation rate.

“A lot of our kids go to work to put food on the table,” says Rancho’s principal, Bob Chesto, explaining why some teenagers drop out of school.

Aide Romero, who teaches English-language learners at Rancho High, adds that a lot of boys drop out because they think they won’t pass Nevada’s high school exit exam. And some girls drop out because they get pregnant, she says.

Educators at Rancho disagree on some aspects of what the state should do for education.

Chesto and Romero would like to see the state develop standardized tests in Spanish for core academic subjects, which they believe would help some of Rancho’s students better show what they know. They’d also want to use the tests to meet state and federal accountability requirements for some of their students.

But Raquel Santana, who teaches applied algebra to English-language learners at Rancho High, doesn’t believe testing in Spanish would help much. “These students have a lack of basic skills,” she says. “This is the huge problem.”

Santana opens a cabinet full of graphing calculators and textbooks to show that she has all the materials needed to help her students. The greatest obstacle she faces in raising their achievement is their mobility, she says.

“Students come and go,” she says. “I can’t work with them consistently. I have a wonderful student and I work hard with him, and then he leaves. The family tries to survive.”