Corrected: An earlier version of this article misstated the number of CES Common Principles. There are ten principles. An earlier version also misquoted Mr. Cohen of the Coalition of Essential Schools. He said that Mr. Sizer’s “ideas were not compatible with the current vernacular of standardization and testing.”

Includes updates and/or revisions.

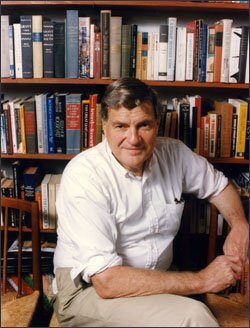

With the death last week of Theodore R. Sizer, precollegiate education lost one of its most influential thinkers and a founder of the contemporary movement to improve schools.

Mr. Sizer died Oct. 21 at his home in Harvard, Mass., of colon cancer. He was 77.

Over his long career, Mr. Sizer was dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, headmaster of the Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass., founder of the Coalition of Essential Schools, chairman of the education department at Brown University, and founding director of the Annenberg Institute for School Reform. More recently, he helped start the Francis W. Parker Charter Essential School in Devens, Mass.

But the lifelong New Englander was perhaps best known for writing the “Horace trilogy” of books—Horace’s Compromise in 1984, Horace’s School in 1992, and Horace’s Hope in 1996—and with them, helping to inspire a nationwide movement to restructure high schools. The books sketched out a vision of schooling that was more personal, more democratic, and more engaging than the large, anonymous “shopping mall” high schools that have typified much of American secondary education.

Mr. Sizer launched the Coalition of Essential Schools, a national reform network, in 1984 to support that vision.

“In the last 50 years, more than anyone else, Ted Sizer carried the torch for progressive education and reinvented it for our time,” said Howard Gardner, a professor of cognition and education at Harvard University.

Lewis Cohen, the executive director of the coalition, which is based in Oakland, Calif., said “the work of Ted influenced so many leading voices in the school reform discussion today.”

Begun with 12 schools, the coalition currently has 150 dues-paying member schools. Hundreds more schools belong to centers around the country that are affiliated with the coalition, according to Mr. Cohen.

Read these Education Week commentaries written by Theodore R. Sizer.

Two Reports

Reform efforts must move beyond today’s narrow habit of conceiving education as only something that adults formally “deliver” to children in classrooms, says Sizer. (April 23, 2003)

On Lame Horses and Tortoises

To my eye, the give-'em-the-nuts-and-bolts strategy is a very threadbare conception of reform, writes Sizer. (June 29, 1997)

Should Schooling Begin and End Earlier?

Age-grading is a modern invention that arose just before the turn of the century from bureaucratic necessity rather than from convictions about human development, writes Sizer. (March 16, 1983)

Coalition schools are organized around 10 basic principles. They hold, among other precepts, that students should learn to “use their minds well” and be seen as valued workers in the community, that teachers should act as mentors rather than deliverers of knowledge, and that instruction should emphasize depth of subject matter over breadth. Learning at the schools is personalized. To graduate, students are required to demonstrate what they can do with the knowledge they have acquired.

“Here was this man in this three-piece suit from Harvard, and he was saying some things that were pretty radical at the time,” recalled Dennis Littky, one of the founding members of the coalition. “He really made all these ideas—student as worker, exhibitions, advisories—come into the mainstream.”

Mr. Littky went on to co-found the Big Picture Learning Company and College Unbound, two Providence, R.I.-based learning networks that he sees as a “next generation” version of the coalition schools.

Mr. Sizer served as the executive director of the coalition until 1997. The network at its peak included more than 1,000 schools, among them some of the biggest success stories in education, such as the famed Central Park East High School in New York City.

CAREER HIGHLIGHTS

• U.S. Army, 1953-55

• Teacher, Roxbury Latin School, West Roxbury, Mass., 1955-56

• Teacher, Melbourne (Australia) Grammar School, 1958

• Assistant professor of education and director, Master of Arts in Teaching program, Harvard University, 1961-64

• Dean, Harvard Graduate School of Education, 1964-72

• Headmaster and history instructor, Phillips Academy, Andover, Mass., 1972-81

• Chairman, A Study of High Schools research project, 1981-84

• Professor, department chairman, and university professor emeritus, Brown University, 1983-96

• Chairman, Coalition of Essential Schools, 1984-96

• Founding director, Annenberg Institute for School Reform, 1994-96

• Acting co-principal (with Nancy Faust Sizer), Francis W. Parker Charter Essential School, 1998-99

• Co-founder, Forum for Education and Democracy, 2003

SELECTED PUBLICATIONS

• Horace’s Compromise: The Dilemma of the American High School, 1984, 2004

• Horace’s School: Redesigning the American High School, 1992

• Horace’s Hope: What Works for the American High School, 1997

• The Students Are Watching: Schools and the Moral Contract (with Nancy Sizer), 1999

• Keeping School: Letters to Families (with Ms. Sizer and Deborah W. Meier), 2004

• The Red Pencil: Convictions From Experience in Education, 2004

Source: Education Week

Partly because of its democratic nature, though, the organization also included some schools that were not so effective, and studies in the late 1990s failed to show that its approach was yielding quantifiable improvements in student test scores across the board.

‘In My Blood’

Mr. Sizer was born in New Haven, Conn., in 1932. His father was a well-known art historian. His wife, Nancy Faust Sizer, is also an educator and writer, and the Sizers collaborated on the Parker charter school, books, and other projects.

In a 2005 interview with Education Sector, a Washington think tank, Mr. Sizer said education “is in my blood.”

“My dad was a teacher, and a German refugee who lived with us after she escaped Hitler was a teacher,” he added. “It was an appealing profession and was reinforced by being in the Army, where I was a teacher, too.” He earned degrees from Yale and Harvard universities.

Horace’s Compromise: The Dilemma of the American High School was Mr. Sizer’s most famous work. Drawn from conclusions reached following a two-year field study of high schools around the country, it told the story of Horace Smith, a fictitious composite teacher frustrated by the bureaucratic limitations of the education system in which he worked. The “compromise” between Horace and his students was: Don’t make trouble for me, and I won’t demand too much of you.

“It brought you face to face with things you knew, but were surprised to see in front of you,” said Marc S. Tucker, the president of the Washington-based National Center on Education and the Economy, who was mentored early in his career by Mr. Sizer. “It captured the man beautifully.”

When the coalition network was well under way, Mr. Sizer went on to lead the Annenberg Institute for School Reform, at Brown University. The institute, begun in 1993 with a $50 million gift from the publisher and philanthropist Walter Annenberg, seeded and continues to support a wide range of school improvement efforts across the country.

“The beauty of Ted was that he could talk to Exxon and college presidents in the same way he talked to students,” Mr. Littky said, “and it was all done in an incredibly respectful way.”

But Mr. Sizer’s influence in the national discourse on education waned as policymakers increasingly emphasized stricter standards, student testing, and educators’ accountability for the results.

“His ideas were not compatable with the current vernacular of standardization and testing,” Mr. Cohen of the Coalition of Essential Schools said. “He believed you really have to know your students and your teaching, and your school has to be responsible to kids as they are and not as data points or widgets on an assembly line.”

Yet, major philanthropies, such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, pursued ideas that reflected Mr. Sizer’s thinking, particularly smaller, more personalized schools. In its first stab at a major investment in school improvement, the Seattle-based foundation sank hundreds of millions of dollars into efforts aimed at downsizing high schools to foster reform. The results fell far short of expectations, however, and Gates has since shifted direction.

Looking back on the movement he helped start, Mr. Sizer said in the 2005 Education Sector interview: “We are disappointed that we haven’t gotten the traction we need.”

“There aren’t many schools that are profoundly different than they were 15 years ago,” he added.

In the last part of his life, Mr. Sizer helped found the Forum for Education and Democracy, which is aimed at preserving and giving a national voice to the ideals characterizing progressive education.

His final book, The Red Pencil, published in 2004, expressed his concerns about standards, testing, and accountability. In the new climate, he wrote, even charter schools run the risk of falling subject to “excessively standardized and politically motivated mandates.”