As it turns out, running a charter school poses different challenges from those of running a traditional public school.

Some of the challenges, of course, are the same. Both charter and regular public school leaders are responsible for shaping a school’s vision, fostering trust between adults and students, managing resources well, and balancing the inevitable pressures inside and outside the school’s environment.

But being a charter school leader brings other challenges not often faced by principals of traditional public schools, who receive support from their districts’ central offices.

For the charter school leader, there is no central office to recruit students and teachers, secure and manage facilities, or raise money and manage school finances.

Now that the charter school movement is halfway through its second decade, how are charter school leaders facing these challenges? What do we know about their experiences?

In 2007, the National Charter School Research Project at the University of Washington surveyed charter school leaders in six states: Arizona, California, Hawaii, North Carolina, Rhode Island, and Texas. We coupled our survey results with the data gathered by the National Center for Education Statistics’ Schools and Staffing Survey, which surveyed both charter school and traditional public school leaders.

Who Are Charter School Leaders?

We learned that charter school leaders are deeply committed and driven by their schools’ individual missions. But they told us that they struggle with all the “extras” of leading a charter school.That’s especially true of leaders with less experience.

On the surface, they look like most traditional public school principals. Our survey found that only 13 percent of charter school leaders moved into their current positions from jobs outside education. This finding is contrary to the expectation that the ranks of charter school leaders would draw heavily from noneducators.

The fifth annual Leading for Learning report, funded by The Wallace Foundation, examines the leadership challenges facing the nation’s rapidly growing charter school sector.

In fact, most charter school leaders are professional educators. Our survey shows the vast majority (74 percent) earned their highest degrees in traditional educational training from colleges of education. Almost 60 percent are or have been state-certified school principals. Their demographic profile, too—race and gender—is not much different from that of traditional public school principals.

A key difference separating charter school leaders from traditional public school principals is their experience with school leadership.

The federal data suggest that almost 30 percent of charter school leaders have led a school for two years or less, compared with only 16 percent of traditional public school principals. Moreover, as many as 12 percent of charter school leaders were under the age of 35—young professionals who, in many cases, jumped straight from teaching into the school leader’s role. On the other hand, some charter leaders are highly experienced. Nineteen percent of such leaders have more than 10 years of experience as school leaders; 28 percent of traditional school principals have comparable experience.

Why Do They Do It?

It is clear from our survey of charter school leaders that what matters most to them is the school’s mission. By definition, charter schools are intended to be missiondriven organizations. They are places conceived of and built around a specific instructional imperative or intended to serve a targeted population of students— often students deemed at risk of failure.

Eighty-six percent of charter school leaders said the school’s mission attracted them to the job. When asked what satisfies them most about their jobs, the top three answers were: passion for the school’s mission; a commitment to educating the kinds of students served by the school; and the autonomy gained by leading a charter school.

Ninety-four percent of charter school leaders surveyed by the National Charter School Research Project said they felt confident or very confident engaging their staffs to work toward the common mission.

Where Do They Struggle?

Set against this dedication to mission are the many practical and administrative requirements for managing a charter school.

Facilities issues top the list of challenges, with about 40 percent of charter school

leaders reporting that securing and managing facilities is a problem. Unlike traditional public schools, charter schools must find their own buildings and pay for these facilities out of the education funds allotted per student.

Personnel and finances come next on the list of struggles. The need to attract good teachers, the constant necessity of raising money, and the challenge of matching expenses with enrollment-driven income are anxiety-provoking and time-consuming concerns for charter school leaders. In a traditional public school, the district’s central office takes care of these issues.

The lack of sufficient time for strategic planning—looking ahead to plot the school’s growth and build its capacity—is another daunting challenge, according to our survey. Almost half the respondents reported not spending enough time on strategic planning.

Nearly one in five charter school leaders reports being only slightly confident or not at all confident in implementing a strategic, schoolwide instructional initiative or schoolwide improvement plan. All of those concerns are more common among leaders with the least experience in the principal’s office.

It follows, then, that experience on the job is the No. 1 factor explaining confidence in charter school leaders, according to the survey, even more so than specialized training and experience.

That said, prior training and experience do play a role. Background in financial management seems to build confidence in the financial aspects of leading schools. Those with prior education from traditional colleges of education seem more confident in overseeing instruction and curriculum in the school. But leaders who have been principals (in public, charter, or private schools) for three years or more are the most confident about both financial and instructional matters.

Preparing for the Change to Come

Our survey also predicts a big turnover of charter school leaders in the near future. Ten percent expect to move on to new opportunities or retire in the next year, and 71 percent expect to have moved on in the next five years. The numbers of new leaders needed are not small, given the 4,300 charter schools currently in operation across in the country.

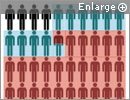

Race and Gender

According to the 2003-04 Schools and Staffing Survey, charter school leaders and their traditional public school peers, for the most part, look similar when it comes to race and gender.

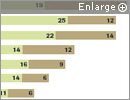

Age and Experience

While the majority of charter school leaders have advanced degrees in education and prior careers in education, they tend to be newer to leadership than traditional public school principals. About 30 percent of charter leaders have directed a school for less than two years. A comparable share of traditional principals have more than 10 years of school leadership experience. Charter school leaders are also more likely to be in their 30’s and less likely to be age 50 or over. There are also slightly more charter leaders younger than 35 and more older than 60. SOURCE: 2003-04 Schools and Staffing Survey, National Center for Education Statistics

School Mission Matters Most to Charter Leaders

Charter leaders are a passionate group, drawn to the school mission, the challenge the work represents, and the opportunity to serve a particular type of student. Few rank “pay and benefits” as a very important factor in taking the job. In fact, about 25 percent reported taking pay cuts when they took their current jobs. SOURCE: Survey of charter leaders in Arizona, California, Hawaii, North Carolina, Rhode Island, and Texas, National Charter School Research Project, 2008

Organizational Challenges in Charter Schools

Charter school leaders say they rarely struggle with mission or even governance issues. In addition, few report conflict with their boards or find compliance and reporting to be a problem. The issues ranked as the most serious problems by charter leaders are finding and managing facilities, hiring qualified and talented teachers, and managing finances.

Confidence to Take on the Job

Charter school leaders are very sure of their abilities in areas related to school culture, with nearly all mostly or very confident in fostering a student-centered learning environment and establishing high expectations for students. More leaders express doubts in the areas of managing finances, hiring teachers, and leading strategic planning. Confidence levels depend on leaders’ experience and other factors. Directors in their first or second year are the least confident in almost every aspect of school leadership.

High Turnover Predicted

As with many careers today, including the traditional public school principal, turnover among charter school leaders is common. One-third plan to leave their current positions in the next three years, and about 70 percent expect to move on in the next five years. Half of those departing charter directors intend to remain in the education field, although few expect to transition to other leadership positions in charter schools. SOURCE: Survey of charter leaders in Arizona, California, Hawaii, North Carolina, Rhode Island, and Texas, National Charter School Research Project

Considering the importance experience plays in managing a charter school, the predicted turnover may be cause for concern. Only a handful of the charter school leaders in the survey said they plan to take on a similar position at another charter school. Instead, respondents indicated they would become school consultants, join charter management organizations, work in school districts or state departments of education, or work as education advocates.

Turnover is not necessarily a problem if schools are prepared for it. But almost half the charter school leaders in the survey could give no specific plan for leadership succession. Fewer than a quarter said their schools were making efforts to cultivate future leaders in those schools.

Leading With the Head, Heart

From recent graduates to those nearing the end of their careers, passionate, hardworking people appear to be stepping up to the challenge of charter school leadership. But our work suggests that such spirit needs to be met with the skills and confidence to handle the everyday demands of the job.

To reinforce their entrepreneurial energy and commitment to mission, charter school leaders—especially those new to school administration—need training and experience in the administrative aspects of their roles as school leaders. They also need willing teachers, staff members, and governing boards that are capable of sharing some part of these leadership tasks.

Expanding peer-mentoring opportunities for leaders is an easy and effective way for new leaders to learn and get support from experienced ones. More charter-specific training options that include meaningful internships would also go a long way to filling gaps in the skill sets of charter school leaders. Public and private financial-incentive programs could help stimulate the supply of more extensive on-thejob training and mentoring opportunities.

Distributing certain administrative, fundraising, and curriculum-development tasks could lessen the burden on charter leaders. Some charter schools do this by sharing leadership within the school. Other charter leaders rely on management organizations to help with the business side, so they can focus on instructional leadership. These strategies may open up more time for strategic planning, while also building management capacity and encouraging others to aspire to the role.

Our survey shows that charter school leaders with a handle on these tasks, especially the tough administrative and management ones, often have handled them before. It’s a case where experience really does matter. Policymakers and funders need to recognize this and help charter schools build the management capacity necessary for their success.

This essay and the accompanying charts and graphs were commissioned for this “Leading for Learning” report from the National Charter School Research Project by the Editorial Projects in Education Research Center. The charter schools project is being conducted by researchers at the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington, in Seattle.

Help could include state and local incentives for leaders to stay on the job, or sabbaticals that would let them refresh and return. Creating stronger incentives for experienced school leaders to try charter schools, and providing funding for promising teachers to receive leadership training, would also help grow a deeper pool of talented leaders.

Running a charter school is challenging. But committed, energetic, and entrepreneurial individuals have taken on this challenge, and countless more are willing to do so. For the charter movement to successfully sustain itself and grow, the commitment of these individuals needs to be reciprocated by the support of those in their schools and in the larger policy community.

The contents of this essay were developed under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education, award number U282N060007. However, it does not necessarily represent the policy of the department, and readers should not assume endorsement by the federal government.