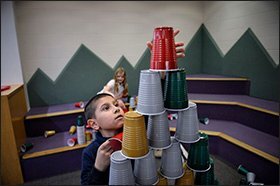

Four days a week, hundreds of children in eastern Pennsylvania get free tutoring, a hot meal, and even the chance to help build a doghouse, thanks to a federal grant for after-school and summer learning programs. Some of their parents get access to English-as-a-second-language and GED classes.

But President Donald Trump’s proposed budget for fiscal 2018 seeks to slash the roughly $1.1 billion 21st Century Community Learning Center program that provides the bulk of the funding for the program and thousands of others like it. Mick Mulvaney, the director of the White House Office of Management and Budget has argued that the program doesn’t have much of an effect on student achievement.

But some advocates and educators beg to differ.

“It just makes my heart hurt. It impacts children’s lives immensely,” said Rachel Strucko, the director of the Leigh Carbon Community College’s Schools Homes in Education program, or SHINE after-school program. “You wonder what is going to happen between those crucial hours of 2 and 6 if there is no after school.”

Thousands of Centers

The program, which has been around since the 1990s, distributes money by formula to states to cover the cost of after-school and summer programs, primarily for children in high-poverty communities. The U.S. Department of Education has funded about 9,600 centers through the program and served 1.6 million children, according to the Afterschool Alliance, an advocacy organization in Washington.

Like SHINE, these after-school and summer programs can offer students a range of services, including tutoring, meals, and enrichment, much of it with the help of federal funds.

For instance, a trio of after-school and summer programs in Cranston, R.I., that receive almost 100 percent of their funding from the 21st Century Community Learning Center program, has a science, technology, engineering, and math focus. Students might help design a greenhouse or build a solar panel from scratch. Older students add a service-learning component, working on neighborhood beautification, for example. Now, the students want to write letters to lawmakers, asking them to preserve 21st Century Community Learning Centers funding, said Ayana Crichton, the program director.

“It’s devastating to them to see the program get cut,” Crichton said. “How come we can’t just talk to the president and tell him” not to cut the funding? she asked.

Some districts also get funding from the program, including the Kennett school system in southeastern Missouri, which receives a $400,000 grant. The district offers students an hour of tutoring in the morning and another hour in the afternoon, plus enrichment. Students are given a hot dinner and transportation home.

“We have a tremendous, tremendous after-school program,” said Chris Wilson, the district superintendent. “If 21st Century goes away, all of that goes away.”

‘Lacks Strong Evidence’

The administration’s budget request says that the program “lacks strong evidence of meeting its objectives, such as improving student achievement.”

Mulvaney was asked specifically about the program during a March 16 press briefing. He said that there isn’t evidence that after-school programs do anything to improve student achievement.

“They’re supposed to be educational programs, right? That’s what they’re supposed to do. They’re supposed to help kids who don’t get fed at home get fed so they do better in school,” Mulvaney said. “Guess what? There’s no demonstrable evidence they’re actually [improving achievement]. There’s no demonstrable evidence of actually helping results, helping kids do better in school.”

Supporters Weigh In

But Heather Weiss, a co-director of the Global Family Research Project, doesn’t see it that way.

“There is a great deal of evidence from rigorous evaluations showing that after-school programs promote a range of important developmental, learning, and educational outcomes for kids,” she said.

She noted that those outcomes include gains in reading and math achievement, school attendance, in socio-emotional development and skills, and in health and wellness.

But Mark Dynarski, who helped conduct evaluations of the 21st Century Community Learning Centers program in the early 2000s as a researcher for Mathematica Policy Research, doesn’t think it has done much to improve student achievement.

“The program didn’t affect student outcomes,” Dynarski, now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, wrote in a March 2015 blog post. “Except for student behavior, which got worse.” He referred to reports on the program released in 2003 and 2005.

Weiss, however, said those reports were conducted years ago and offer only a snapshot of the program in its early stages. After-school programs, including those that receive 21st Century Community Learning Center funds, have gotten a lot more sophisticated since then, she said.

They’ve been “focusing on quality improvement and using their own and others’ evaluations and data to ensure quality and get bigger and sustainable impact,” Weiss wrote in an email.

It’s tough to say if lawmakers will go along with the proposed cut, which would affect the budget year that begins Oct. 1.

Congress had actually considered getting rid of the language in the Elementary and Secondary Education Act that authorizes the 21st Community Learning Center program when it crafted the Every Student Succeeds Act in 2015.

But the program was saved by its fans on Capitol Hill, including Rep. Lou Barletta, R-Pa., an ally of the president who helped co-found the “Trump caucus” in the House. (Barletta has visited SHINE, which serves children in his district.)

And earlier this month, Barletta teamed up with Rep. David Cicilline, D-R.I., on a letter to Mulvaney, asking him to restore the 21st Century Community Learning Centers program in the budget.