The United States and the international community need to make the education of Iraqi children a higher priority, the actress and refugee advocate Angelina Jolie said April 8 at a panel discussion sponsored by the Council on Foreign Relations about children affected by conflict in their countries.

“To reach them and help them deal with their future, it should be one of our highest priorities,” she said.

The actress, a goodwill ambassador for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, has visited strife-ridden Iraq twice in the past year. When she met with Iraqi families, parents told her a pressing issue is how to get their children into school, she said. “Iraq has a history of a high-quality education system. So they are aware of their loss.”

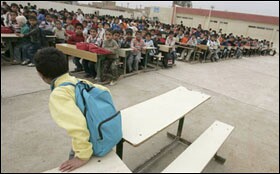

Ms. Jolie described some schools there as being overcrowded and said others were being used as housing for Iraqis displaced by the war, now in its sixth year. She characterized international efforts to provide education for Iraqi children and other children living in areas of violent conflict as a “drop in the bucket.”

She was joined in that view by Gene Sperling, the director of the Center for Universal Education at the Council on Foreign Relations, with whom she co-chairs the Education Partnership for Children of Conflict. Mr. Sperling said children in war-torn countries are often overlooked because other nations don’t want to give to governments perceived to be fragile. In addition, said the former national economic adviser to President Clinton, “education is often last in line in a humanitarian-crisis situation.”

Officials from UNICEF recently said that last school year 50 percent to 60 percent of Iraq’s children were enrolled in the country’s primary schools, although they said attendance rates were likely much lower. Statistics for this school year aren’t available.

Iraq’s high-quality education deteriorated over several decades and has been affected by violence and sectarian conflict resulting from the current war, said another panelist, Safaa El-Kogali, a senior economist for the World Bank and a team leader for the World Bank’s Iraq education programs.

During the war, insurgents have targeted educators, Ms. El-Kogali said. “Teachers and students have had to move continuously, and sometimes in opposite directions,” she said. As a result, some schools have too many teachers and others don’t have enough.

Since 2003, about 2,750 schools in Iraq have been destroyed, Ms. El-Kogali said. The Iraq Ministry of Education estimates the country needs 4,000 new schools, she said.

“The security situation remains very serious,” Ms. El-Kogali added.

Girls Out of School

Read more stories from our special collection, Iraqi Schoolchildren: 5 Years of War.

Several others on the panel sponsored by the Washington think tank expressed concern that far fewer Iraqi girls are attending school than boys—about one girl attends for every four boys, Mr. Sperling noted. That represents a shift from the situation prior to the war.

George Rupp, the president and chief executive officer of the International Rescue Committee, with headquarters in New York City, which provides relief to refugees, also noted that the children of many Iraqis who have fled their homeland and are living in Syria and Jordan are not attending school. He said that Iraqi refugees aren’t permitted to work in those countries, yet some have resorted to having their children work illegally.

In addition to calling on the United States to provide more money to serve the humanitarian needs, including education, of Iraqis, two of the panelists—Ms. Jolie and Mr. Rupp—urged the United States to pick up the pace in admitting Iraqi refugees to the United States.

Ms. Jolie said the United States took in 375 Iraqi refugees in January, 444 in February, and 751 in March. While heartened that the rate of acceptance is increasing each month, she said the United States is still 9,000 short of reaching its stated goal of admitting 12,000 Iraqi refugees in fiscal 2008.