During his last week in office, Grover J. “Russ” Whitehurst, the recently departed director of the U.S. Department of Education’s top research agency, got a going-away present: a glowing five-year evaluation from the independent board that advises his agency.

Posted online Nov. 20, the congressionally mandated report credits the 6-year-old Institute of Education Sciences for improving the quality of federally financed education studies and attempting to make its work more relevant.

“A new direction has been set for education research,” the 15-member National Board for Education Sciences concludes in its report. “We now need to stay on course.”

Created in 2002 by an act of Congress, the IES took on the mission of transforming education into an evidence-based field, much like medicine.

Some critics complained that the agency focused too much on a research method known as randomized controlled trials, while giving short shrift to other approaches. Department officials defended the emphasis on such experiments, which involve randomly assigning participants to either experimental or control groups, as the “gold standard” for determining if an intervention works.

In its report, the board, whose members were all nominated by President George W. Bush and confirmed by the Senate, said the institute’s early emphasis was well placed. “The only way for research to improve student outcomes is for the research to be of high quality,” the report states.

It also notes, contrary to the widespread perception about the agency’s single-minded focus on experimental work, that only a quarter of the research grants the agency approved from 2003 to 2008 fell into that category.

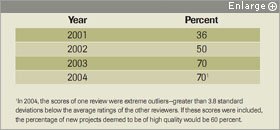

Year | Percent

2001 | 36

2002 | 50

2003 | 70

2004 | 70

The percentage of new research and evaluation projects that were deemed to be of high quality by an independent review panel rose after 2001, the year before the Institute of Education Sciences was established, a new review says.

In 2004, the scores of one review were extreme outliers—greater than 3.8 standard deviations below the average ratings of the other reviewers. If these scores were included, the percentage of new projects deemed to be of high quality would be 60 percent.

Note: IES projects reported in this table exclude grants funded through the National Center for Special Education Research.

SOURCE: Institute of Education Sciences

Such experiments do account for the lion’s share of work financed by the National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, one of the four centers under the IES’ umbrella. That is because the NCEE’s work involves contracting out congressionally directed evaluations of federal programs and policies.

Mr. Whitehurst called the report “appropriately positive.”

But a more critical view came from the American Educational Research Association, the Washington-based group that represents 26,000 education researchers.

“The five-year IES report is a seamlessly self-congratulatory statement pointing out the numerous accomplishments but ignoring the rough patches,” said Gerald E. Sroufe, the association’s government-relations director.

Progress and Problems

For its report, the board drew on data gathered by Synergy Enterprises Inc., a Silver Spring, Md., research firm; the Center for Evaluation and Education Policy at Indiana University in Bloomington; and the agency’s own internal statistics, said Robert C. Granger, the board’s current president.

In terms of research quality, the data showed that the proportion of agency-financed research projects rated by peer reviewers as “excellent” or better rose from 88 percent in 2003 to 91 percent in 2008.

The report also documents a rise in the number of research grants rated by external reviewers as “relevant.” On a scale of 1 to 9, the ratings rose from 5.5, on average, in 2001, the year before the institute was launched, to 6.5 in 2007.

The board also praised the agency for setting up new grant programs aimed at supporting states that are building longitudinal systems for collecting student-achievement data and at establishing new pre- and postdoctoral training programs for budding education researchers.

When it comes to the turnaround on IES reports, though, the board’s report cites both problems and progress. It notes that, while the IES’ main statistics arm, the National Center for Education Statistics, in recent years dramatically reduced the amount of time between collecting data and first publishing a report, delays continue to be a problem at the NCEE, where finished reports got stuck in the review pipeline for an average of 28 weeks since 2007.

“It breeds a feeling that things are being slowed up for political reasons, and that’s not healthy for anyone,” said Mr. Granger, the president of the William T. Grant Foundation of New York City.

The report did not address the broader cultural change that the agency brought about in the field, said Frederick M. Hess, the director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, a Washington think tank.

“We’ve seen this enormous shift in basic assumptions in what is and is not valid research,” he said. “My concern is that there hasn’t been as much attention to what are the limits of this kind of research.”