Julie Reulbach doesn’t sell resources on Teachers Pay Teachers, an online marketplace where educators can make money on their lesson plans and classroom materials. Even so, she often sees her work for sale there.

“Everytime I check, I find something,” said Reulbach, a high school math teacher at a private school in Concord, N.C., who has published an instructional blog since 2010. She scans TpT for work from her blog about once every six months. Her site is under a NonCommercial Creative Commons license, so anyone can use, edit, or share her materials—but they are not supposed to sell them.

It’s happening anyway. And Reulbach’s experience isn’t unique.

Nearly a dozen educators who have used or are knowledgeable about the site told Education Week that TpT has a widespread problem with copyright infringement. Teachers said sellers had lifted passages verbatim from their lessons and copied entire pages without permission. While the company provides a reporting mechanism for infractions, it leaves the policing to the rights holders themselves.

The controversy over stolen work has also fueled a larger ideological rift in the teaching community: the division between those who think it’s fine for teachers to make money off their hard work, and those who believe educators should share materials with their colleagues for free.

In a statement, TpT CEO Joe Holland said that the company takes the protection of intellectual property seriously.

“TpT strictly prohibits its sellers from listing material that infringes on the intellectual property rights of others, and we have no desire to have such material on TpT,” he said.

But educators and authors say the company should be doing more to combat what they see as a systemic failure to protect teachers and others who create materials.

‘They Shouldn’t Be Selling It’

When Reulbach sees sellers attempting to make money off of lessons she’s created, she reaches out to them and asks them to take her materials down. “Usually, people contact me and say, ‘I’m really sorry,’” and remove the resource from their store, she said.

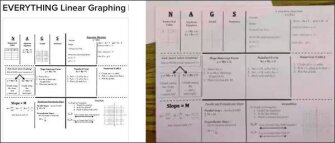

But earlier this year, she got into an argument with a teacher-seller that veered into the public sphere. Seeing one of her graphic organizers for sale in a TpT store, Reulbach filed a notice with the company’s copyright team and commented on the listing. She also reached out to the seller, Theresa Ellington, on Twitter, asking her to remove the product.

The two went back and forth on the social media platform, with Ellington saying that she had reworked the lesson from a Pinterest post and Reulbach maintaining that the resource was a direct copy of hers.

Screenshots Reulbach took of the worksheet from the store are nearly identical to the version in her original blog post, including the same formatting and equations. One picture published with Ellington’s product even shows a photo of the organizer filled out in Reulbach’s handwriting.

Eventually, Ellington, a math teacher and educational consultant, removed the graphic organizer from her store. But in an interview with Education Week, Ellington said she didn’t believe that the resource ever infringed on Reulbach’s copyright. She said she made changes to the Pinterest post and sold it so that other teachers could have access to the updated version. (She also said no one ever actually bought a copy from her.)

Reulbach often finds pictures of her work posted on Pinterest, she told Education Week, where teachers might assume that the images don’t belong to anyone. “But obviously, if they didn’t create it, they shouldn’t be selling it and trying to make money off of it,” she said.

Other teachers say they’ve unexpectedly found their work being sold on TpT as well.

When Chicago teacher Tess Raser found out that her 6th graders would be seeing the movie “Black Panther” as a class, she saw an opportunity for a powerful lesson. Raser created an accompanying curriculum for the movie, covering a wide swath of history, social studies, and sociology: African kingdoms, the trans-Atlantic slave trade, Afrofeminism, and Afrofuturism.

She posted the resource online, and it went viral. Raser’s work was featured on the technology and science fiction site Gizmodo and on the site for Blavity, a media company geared to black millenials. Teaching Tolerance, a social justice and anti-bias program that provides free resources for educators, also highlighted it as recommended reading. While access to the Google doc with the curriculum was free, Raser asked that those who could pay her do so via Venmo or the Cash App, two online payment services. She also posted the resource for sale on her own TpT store.

Months later, a friend emailed her—another TpT seller had listed a resource with content almost identical to her own, she said. A preview page from the seller’s lesson shows the same objectives around understanding colonialism and a similar picture-matching activity. Raser emailed TpT to report the seller and posted about the incident on Twitter. And though the seller did remove the resource from her store, Raser didn’t feel that the problem had been resolved.

“I was like, OK, well, you still need to compensate me because you’ve been paid for work that I created,” she said. “I don’t care that it’s deleted—you shouldn’t have put it up in the first place.”

Raser said she left comments on the seller’s other listings asking for payment and emailed the company inquiring about compensation. But TpT told her that beyond removing the resource, there wasn’t anything the company could do. Raser could get a lawyer, the company told her, if she wanted to pursue a case against the seller.

TpT doesn’t arbitrate copyright claims. The company complies with the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, which updated copyright law to address publication and distribution on the internet. The law gives websites that host third-party content, like TpT, what’s called a “safe harbor.” When sellers on the platform post material that infringes on someone else’s copyright, the company is not held financially liable.

In order to claim this legal protection, TpT has to give copyright holders a way to flag infringing content and have it taken down. Anyone who thinks a TpT seller has listed his or her copyrighted material can submit a DMCA takedown notice with the site. Every product has a “report this resource” option, which leads to an electronic form, or users can also email the company directly.

On its website, TpT says that if it receives a DMCA notice with all of the required information included, it will remove infringing content. The company would not say how many DMCA notices it receives on a yearly basis.

And the burden is on teachers to file infringement complaints—not on TpT to police seller content. TpT doesn’t independently review the content on the site, in part because it’s difficult for the company to know what agreements or licenses individual sellers have. For example, a seller using large, verbatim passages of someone else’s work could be infringing on copyright—or might have permission from the original author to use those sections for commercial purposes.

For Raser, the seller’s silence was especially astonishing, given the subject matter of her materials. “Literally, it’s curriculum on colonization and the legacy of slavery,” she said. It was “ludicrous,” Raser said, that someone would take resources created by a black woman on those topics, pass them off as his or her own, and profit off of them. The seller, who is only identifiable by screenname, did not return several requests for comment.

After Raser commented on the seller’s page asking for compensation, TpT told Raser that it had received reports of her harassing a member of the site. If the company received more of these reports against her, the email read, TpT would suspend or deactivate her account. The seller’s account is still live.

Public Pressure

Some who’ve had their content lifted say they see public pressure as their best recourse.

Reulbach, the North Carolina teacher, said the reporting process through TpT can be slow, and contacting the seller directly sometimes yields a faster result.

But Ellington, whom Reulbach confronted on Twitter, said she felt that Reulbach was wrong to handle the incident publicly. “I felt like it was more cyberbullying than legitimately two people, two teachers, two professionals speaking about, ‘Hey, this is an issue,’” she said.

When TpT did respond to Reulbach, it was only to say the company would note Ellington’s infraction in its records.

Reulbach’s social media callout did have another effect: It led to an avalanche of Tweets from other bloggers who’d had similar experiences.

Lisa Bejarano, a former high school math teacher who now works for the online graphing calculator company Desmos, was one of these bloggers. Bejarano has seen resources from her blog sold by other users, but she said it’s not worth the energy for her to fight stolen work. She’s reached out to sellers when similarities to her work have been pointed out to her by friends or colleagues, but she doesn’t go looking for infractions.

“Usually as a teacher, you’re just so busy trying to grade and plan and teach that policing is the last priority,” she said.

Investigating possible infringement can carry a financial cost for teachers, too. Browsers on TpT can only see a small selection of preview pages from resources that they haven’t purchased, so it can be necessary to buy a product to confirm a suspicion that it’s copied from another work, said Bejarano.

“My perspective is always that if that teacher is that desperate to make a couple extra bucks that they need to go to these lengths, then they have bigger issues that I’m not going to fix,” she said.

The company says it will close the accounts of sellers who are reported multiple times for copyright infringement, but wouldn’t say how many individual infractions it would need to receive against someone before taking this step.

Several teachers argued that TpT didn’t have an incentive to police the site, because the company profits off of every lesson sold. It takes a 45 percent commission from every lesson purchased from a regular seller and a 20 percent commission from every sale from a “premium” seller—a paid membership tier that costs about $60 a year.

“Teachers Pay Teachers is making money off of copyrighted material, and they’re putting it on the responsibility of the teachers who created the material to go hunt that down, and make sure it comes off. And that’s what makes me angry,” said Reulbach. “It’s not about me. It’s about a corporation that’s making money off of copyrighted material.”

In a statement, Holland said the company has “no desire” to have material that infringes copyright listed on TpT.

Ethics of Selling vs. Sharing

When TpT first started in 2006, a controversial debate launched along with it: Is it ethical for teachers to charge each other for lessons and resources, or should they share their creations with each other for free?

TpT has been heralded as a way for underpaid educators to make extra money—media coverage has frequently spotlighted teachers who have pulled in six-figure profits.

Many of the problems on Teachers Pay teachers and similar sites arise simply because there’s confusion around the laws for creating, sharing, and selling intellectual material, including lesson plans and classroom activities.

“People don’t know, and why would they know?” said Carrie Russell, the senior program director for public policy and advocacy at the American Library Association.

For teachers who aren’t sure what their rights are, here are three general tips:

• Copyright protection begins at the point of creation: As soon as a teacher finishes a work, she holds the rights.

• Having the copyright registered with the U.S. Copyright Office will provide evidence to a court that the teacher is the rightful copyright holder if there were ever an infringement case. A teacher can sue without registering her copyright, but she would still need to prove that she was the original author of the work.

• Teachers should consider labeling their work with a copyright symbol, their name, and the date of creation. While this won’t change their legal rights, it could be a deterrent for potential infringers.

But the customers on TpT are also teachers, who are facing financial strains similar to the sellers. Should they really have to pay for the materials needed to do their jobs?

Bringing up issues of copyright infringement on the platform can set off a powder-keg in the teacher-seller community, Reulbach said. Criticism of the problem, she said, is often mistaken for criticism of all teachers who use the site.

“It’s a very, very sore subject for a lot of teachers, because some teachers really do need Teachers Pay Teachers to survive,” Reulbach said. And teachers in underresourced schools rely on the centralized store of lessons and materials.

As TpT has become popular, opportunities for online sharing have also developed—platforms like BetterLesson and Share My Lesson allow teachers to freely post and download material. There’s also a growing sect of teachers who create and use HyperDocs: editable, shareable lessons hosted on Google docs. That movement’s website is titled “Teachers Give Teachers.”

If material is good enough to share, it doesn’t make sense to limit teachers’ and students’ access to it by charging a fee, said Kevin Roughton, a middle school social studies teacher in southern California, who said he’s also seen his work sold on TpT without his permission. “If my work can help the teacher next door, I’m certainly not going to charge my colleague next door. ... I don’t know why, all of the sudden, if it’s [a teacher in] another county or another state, that I’d want to limit students from having access to that material.”

Roughton publishes a blog where he shares the history lessons that he creates. Last year, he found a lesson with several lines of text lifted verbatim from his materials in a TpT store. He contacted the seller, who acknowledged the similarities and said he may have subconsciously included lines from other resources he had seen online. The seller then made changes to the product.

“Ideas in the education community are shared and borrowed and stolen all the time,” Roughton said. But there’s a difference, he said, between “stealing” an idea to use with your own students and stealing work to sell for profit. The former is good instruction, while the latter is at best bad practice—and at worst, illegal.

For Reulbach, seeing her work behind a paywall feels like a barrier to equity. “Teachers don’t make a lot of money, and it just really makes me sad that teachers are paying for something that they could get for free,” she said.

Need for Clarity

Sellers aren’t just lifting resources from individual teachers—they’re taking from commercially published materials as well.

Jennifer Serravallo, who’s written books on teaching reading and writing strategies, is one of the many education authors whose work is popular with TpT sellers. Users create activities inspired by these authors’ work and resources to complement the lessons in their books. Sometimes, though, they also include chunks of these authors’ books, which are protected by copyright.

Searching Serravallo’s name on the site returns more than 100 products, created by other users, that reference her work. Some of them clearly violate copyright, she said—like word-for-word passages lifted from her books—but others she doesn’t flag, like when sellers reference her list of reading goals or the title of one of her books within their product. “I don’t think that’s a problem,” she said. Making these judgment calls can be difficult, and it requires an intimate understanding of her published work, said Serravallo.

Serravallo thinks that a lot of the problems stem from teachers not understanding the ins and outs of copyright law. “The teachers who are making this stuff have always been horrified as soon as they’ve been called out,” said Serravallo, expressing remorse that they’ve violated the work of an author they respect.

“I don’t think there’s malicious intent. I don’t think they’re trying to be sneaky ... I think they, in many cases, just really don’t know that what they’re recreating is a violation. They think it’s just going to be a helpful resource out there.”

The issue is hardly limited to Serravallo’s work. Her publisher, Heinemann, recently updated the copyright language in its books, directly in response to teachers using work from its imprint on TpT and other sites: “We respectfully ask that you do not adapt, re-use, or copy anything on third-party (whether for-profit or not-for-profit) lesson-sharing websites.”

And many teachers don’t realize that they’re generally violating copyright by pulling a photo or image from the internet that they don’t have rights to use.

TpT has a “deep respect for intellectual property rights,” said TpT CEO Holland, in a statement. “To that end, we ask our sellers to certify to the ownership of their resources upon account creation.” Sellers have to re-confirm they’re posting original work each time they upload a new resource. (TpT would not offer public comment beyond the written statement for this story.)

But copyright laws are complex and nuanced, said Serravallo. “As an author, I have learned a lot about this because I try to put stuff in my books, and it’ll get flagged” by the publisher’s permissions department, she said. Even now, after publishing several books, she still is surprised by some of the material the department tells her she can’t use. For a teacher self-publishing content on TpT, navigating those rules without legal counsel would be difficult, said Serravallo.

The company provides several informational resources on copyright and trademark, including a three-part explanation of copyright protections, a quiz, and FAQ sections for sellers and buyers. But teacher-sellers aren’t required to review these resources or demonstrate understanding of copyright protections before they start listing products.

Unfair Burden?

Educators say that the company should be doing more—to simplify the reporting process, to better educate sellers about copyright law, to take swifter action against those who break the rules.

Roughton, the teacher from southern California, never filed a DMCA takedown notice with the site. He said he knew that he had created the material, but he wasn’t sure if he needed to do anything to claim copyright. (He did not.)

He was worried that if his claim weren’t seen as valid he could get in legal trouble himself. “As a teacher, I was like, it’s just not worth it for a $5 lesson on a website,” he said.

When users do file DMCA notices, they have to separately report each listing. Sometimes, said Serravallo, a user will create individual resources that infringe on her copyright, and then bundle all of those resources into another, distinct product. In those cases, she has to report the bundle as well as each individual resource.

“It’s a lot of work for the author to make something right that [someone else has] done wrong,” said Serravallo.