Reaching the threescore-and-ten milestone recently, and embarking on a new role at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, prompted me to do some stocktaking on the state of American education in 2014.

I’ve been at this for ages, notably since Diane Ravitch and I launched the Educational Excellence Network in 1981. Two years before A Nation at Risk, we—and a handful of fellow travelers—had concluded that American education needed a kick in the pants, a kick toward greater quality, primarily in the form of stronger student learning.

That was before many of today’s ed reformers were born—a growing army of compatriots with whom I still march.

What has been accomplished in three decades-plus? A lot, actually, beginning with two epochal changes:

First, we now judge schools by their achievement results, not their inputs or intentions. And while we still struggle with the details, over the years we’ve developed academic standards that set forth the results we seek, created measures to gauge how well they’re being achieved, built a trove of data that generally makes results transparent and comparable, and constructed accountability systems that reward, intervene in, and sometimes sanction schools, educators, and students according to how well they’re doing.

And, second, choice among schools has become almost ubiquitous. Though too many choices are unsatisfactory, and too many kids don’t yet have access to enough good ones, we’re miles from the education system of 1981, which took for granted that children would attend the standard-issue, district-operated public school in their neighborhoods unless, perhaps, they were Catholic (or very wealthy).

Plenty more gains deserve mention, including the serious entry of technology into classrooms, ambitious teacher-evaluation systems, networks of charter schools that do a bang-up job of educating poor kids, some rewards for outstanding educators (and some softening of job protections for the other kind), and a host of “alternative” routes into classrooms and principals’ offices.

Yes, there’s much to be proud of—and millions of American children (and the nation itself) now benefit from the reformers’ labors.

Chester E. Finn Jr. has been a frequent contributor to the Commentary section of Education Week for more than three decades, beginning with the back-page essay that appeared in the Sept. 7, 1981, inaugural issue.

Browse through some highlights from Mr. Finn’s prolific run below.

- Trashing The Coleman Report (Sept. 7, 1981)

- Questioning ‘Cliches’ of Education Reform (Dec. 25, 1989)

- Does ‘Public’ Mean ‘Good’? (Feb. 12, 1992)

- Memorandum to the President From Chester E. Finn, Bruno V. Manno, and Diane Ravitch (Dec. 24, 2001)

- Lessons Learned (Feb. 27, 2008)

But we have so far still to go. The reform seeds that we’ve planted don’t yet yield nearly enough harvest of student achievement or school performance, particularly at the end of high school, when it matters most. We still have too many unforgivable gaps, too many “dropout factories,” too many kids left behind, too many without great options. Other countries are making faster gains. And we haven’t yet worked our way down the agenda of essential reforms. Let me note eight of the toughest and most consequential challenges ahead.

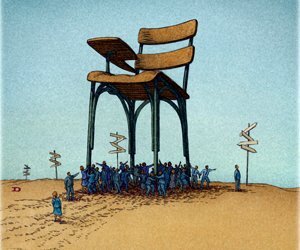

Governance. The basic structural and governance arrangements of American public education are obsolete. We have too many layers, too many veto points, too much institutional inertia. Local control needs to be reinvented—to me, it should look more like a charter school governed by parents and community leaders than a vast Houston- or Chicago-style citywide agency—and education needs to join the mayors’ (and governors’) portfolios of other important human services. Alternatives are emerging—mayoral control in a dozen cities, “recovery” school districts in a few states, and more—but the vast majority of U.S. schools remain locked in structures that may have made sense around 1900, but not in 2014.

Finance. I dare you to track, count, and compare the dollars flowing into a given school or a given child’s education. I defy you to compare school budgets across districts or states. I challenge you to equalize and rationalize the financing of a district or state education system—and the accounting system that tracks it—in ways that target resources on places and people that need them and that enable those resources—all those resources—to follow kids to the schools they actually attend. What an unfiltered mess!

Leaders. We’re beginning to draw principals, superintendents, chancellors, and state chiefs from nontraditional backgrounds, but we haven’t turned the corner on education leadership. We still view principals, for example, as chief teachers—and middle managers—rather than the CEOs they need to become if school-level authority is ever to keep up with school-level responsibility. We already hold them accountable as executives, but nothing else about their role has yet caught up.

Curriculum and instruction. “Structural” reformers—I plead guilty to having been one—don’t pay nearly enough attention to what’s happening in the classroom, in particular to what’s being taught (curriculum) and how it’s being taught (pedagogy). The fact is that content matters enormously—E.D. Hirsch Jr. of the Core Knowledge Foundation is exactly right about this—and that some instructional methods work better in particular circumstances than others. Both standards-based and choice-based reform have remained largely indifferent to these matters, but that ought not continue.

Though too many choices are unsatisfactory, and too many kids don't yet have access to enough good ones, we're miles from the education system of 1981."

High-ability students. Smart kids deserve education tailored to their needs and capabilities every bit as much as youngsters with disabilities. And the nation’s long-term competitiveness—not to mention the vitality of its culture, the strength of its civic life, and much more—hinges in no small part on educating to the max those girls and boys with exceptional ability. Yet gifted education in America is patchy at best; at worst, it’s downright antagonistic to the needs of these kids.

Preparation of educators. How many times do people like former Teachers College President Arthur Levine and organizations like the National Council on Teacher Quality have to document the failings of hundreds upon hundreds of teacher- and principal-preparation programs before this gets tackled as a top-priority reform? Once again, promising alternatives are emerging, and a smallish number of traditional programs do a fine job. But, once again, the typical case is grossly inadequate.

Complacency. Two forms of complacency alarm me. The familiar one is the millions of parents who deplore the condition of American schools in general but are convinced that their own child’s school is just fine (”... and that nice Ms. Randolph is so helpful to young Mortimer”). The new one, equally worrying, is reformers who think they’ve done their job when they get a law passed, an evaluation system created, or a new program launched, and then sit back on their haunches, give short shrift to implementation, and defy anyone who suggests that their proud accomplishment isn’t actually working.

Greed. I hail the entry into the education reform camp of entrepreneurs with all their energy, imagination, and venture capital, but I’ve seen too many examples of their settling for making their venture profitable for shareholders rather than kids. That’s not so different from traditional adult interests within the public and nonprofit sectors battling to ensure their own jobs, income, and comfort rather than giving their pupils top priority. A firm that’s just in it for the money is as reprehensible as a teachers’ union that’s in it just to look after its members’ pay, pensions, and job security.

That’s more than enough to keep the reform army fully engaged for at least another 33 years. I’ll march with them as long as I can, as will my Fordham Institute colleagues. This war needs to be won. My grandchildren are counting on it. So will yours.