Includes updates and/or revisions

In the research on dropouts, the experiences of students like Robert Ortega, an 18-year-old senior at San Bernardino High School in California who dropped out of high school and re-enrolled twice, were once an invisible piece of the puzzle.

That’s because most studies on dropouts tend to focus on their numbers and what causes them to give up on school. A study released last week by researchers from WestEd, a San Francisco-based research group, takes a different tack, shedding a spotlight on the students who come back.

The study examines what happens to high school dropouts when they return to their studies, whether they graduate on the second, third, or fourth try, and the systemic disincentives that conspire to keep them out of the classroom.

“These are truly resilient, remarkable people,” said BethAnn Berliner, a senior research associate at WestEd and the study’s lead author. “And large urban districts with high rates of low-income families and high rates of retries are confronted with lots of disincentives to re-enrolling them.”

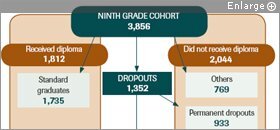

For their study, which was conducted for a federal regional education laboratory that WestEd runs, Ms. Berliner and her colleagues tracked 3,856 students from fall 2001, when they entered 9th grade in San Bernardino city schools for the first time, until 2006, when most had finished high school.

Even though the study focused on San Bernardino, a 59,000-student district south of Los Angeles that has drawn negative publicity for its high dropout rates, the findings have implications for many districts nationwide, experts said.

“I expect there are some differences among districts, but, by and large, these conditions exist in a lot of schools,” said Thomas Timar, a professor of education policy at the University of California, Davis, and the director of the university’s Center for Applied Policy in Education. “Trying to find ways of making it easier for students to re-enter school is probably not something that people have the time and inclination to do,” added Mr. Timar, who was not part of the WestEd study.

Out and In

Of the students the study tracked, more than a third—1,352 students—dropped out of school at least once over the five years of the study period. Yet for a sizeable proportion of those students, as for Mr. Ortega, dropping out was not a permanent condition.

Thirty-one percent of the dropouts, or 419 students, re-enrolled at some point. In the end, though, only 77 of the repeat students went on to graduate within five years.

The researchers also found that 15.5 percent of the returning students came back more than once. Fourteen percent of the returning students—59 students—re-enrolled twice and six students made three tries for their diploma.

“But our data underrepresents the problem,” added Ms. Berliner. “The students’ perception was that they had dropped out and come back more times than showed up on legitimate paper.”

For background, previous stories, and Web links, read Dropouts

The study also found that, compared with African-American students, Hispanic students were more likely to drop out and less likely to re-enroll, possibly because many such students in San Bernardino often move back and forth between the United States and Mexico, where researchers are unable to track them. White students and Asian-American students, who had lower dropout rates to begin with, also re-enrolled at lower rates than black students.

The students who dropped out did so for all the typical reasons, including family problems, mounting course failures, poor academic skills, homelessness, and the lure of gang life, according to the study, which drew on interviews with students and teachers as well as district statistics. The researchers found that a similar set of factors push and pull students back to school.

“The primary push was that there was no place in the economy for a teenager without a high school diploma,” Ms. Berliner said. “The primary pull was a caring adult—for the most part, principals and coaches—who understood students’ life story and said, ‘Come back, we’ll do whatever it takes to get you back in school.’ ”

In Mr. Ortega’s case, as with many students, family responsibilities also played a leading role in leaving. Mr. Ortega left school in his sophomore year after his mother became fatally ill. Faced with having to take care of her, raise his three nephews, and earn enough money to support the family, the teenager felt he had no choice but to drop out.

While many dropouts from a large California district never returned, a substantial slice of them re-enrolled at least once. Nearly 85 percent of those re-enrollees did not manage to graduate, however.

SOURCE: WestEd

He re-enrolled last November after his mother died and his estranged sister took the family in.

“I always promised my grandfather that I would finish high school one way or another,” he said in an interview. “It blew my mind, finding out that the school was able to set me back in and get me the chances I need to finish.”

Aware of his personal problems, school officials arranged Mr. Ortega’s schedule so that he could take core academic classes early in the morning and then leave school in time to be home when his younger nephews returned from school.

Dearth of Options

In that respect, Mr. Ortega may be luckier than some of the re-enrollees who preceded him. At the time of the study, none of the district’s five traditional high schools had programs in place to help students recover credit for missed or failed courses, which was found to be a major reason that students drop out a second and third time.

Returning students, for the most part, were treated like any other student, the report found, sometimes returning to the same classes that they had already failed once.

Flexible scheduling, self-paced study, and credit-recovery programs are options at the district’s two “continuation schools,” which is what California calls alternative schools specifically aimed at troubled students. But in San Bernardino, the wait to get into those schools can be as long as a year.

Also, students don’t become eligible for some of the accelerated credit-recovery programs at the continuation school, or for adult education programs, until they are 16 or older, according to the report.

The problem is that 60 percent of the students who come back dropped out in their freshman year, when they were typically 14 or 15, according to the study.

And neither students nor educators view district summer school programs, which are geared to helping students pass state exams, as a good way to earn back credit.

“There needs to be some way to retrieve credits quickly so students don’t fall so far behind, feel hopeless, and drop out,” Ms. Berliner said. One result of the lack of options: A third of re-enrollees leave school before earning even one class credit, the study found.

San Bernardino school officials, for their part, have long put a high priority on luring dropouts back to school. Two years ago, for instance, the district began a twice-a-year campaign to recover errant students, sending staff members to knock on the doors of as many as 700 who hadn’t been showing up for class. The district also offers a middle college high school, Internet-based courses, a fifth-year schooling option, and programs for pregnant and parenting students to keep them on track to graduate.

Built-In Barriers

But school officials and researchers said educators also get penalized for re-enrolling dropouts because of built-in disincentives in the state and federal school systems.

“Under No Child Left Behind, a teacher has to be focused on raising test scores,” said Arturo Delgado, the district superintendent, referring to the far-reaching federal law on K-12 education. “That teacher may not feel very rewarded when we show up and say, ‘Congratulations, here are five or six students who’ve been out the last six months,’ because that student might drag down test scores.”

What’s more, under state accountability rules, districts “get dinged,” as Ms. Berliner puts it, for graduating students in five years, rather than the usual four, and dropouts who re-enroll and then drop out again are counted as two separate dropouts. “Then the school gets labeled a dropout factory,” said Mr. Delgado, “and people lose confidence in the system.”

The report also suggests that, because the returning students often have sporadic attendance and take longer to graduate, districts lose out under the state’s school finance system, which calculates per-pupil funding based on a district’s average daily attendance over the course of the previous school year.

Russell W. Rumberger, a professor of education policy at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and the director of the California Dropout Research Project, said the WestEd study is among a growing number of much-needed longitudinal studies tracking actual dropout patterns among high school students rather than relying on statistical calculations.

He said all the studies underscore the importance of 9th grade as the make-or-break year, and of accumulating course failures as a key trigger in students’ decision to leave school. “The kids with less course failures are the kids who re-enroll,” he noted.