Campaigns in individual states to legalize marijuana use may be contributing to a drop in the percentages of teenagers nationwide who see risk in regular use of the drug and to an increase in its use by students themselves, public-health leaders say.

Experts say that shifting attitudes about the drug complicate schools’ drug-abuse-prevention classes, where teachers must navigate conflicts between state and federal drug laws, disputes about the effects of marijuana, and, increasingly, a contrast between how marijuana is discussed in the classroom and how it is discussed in students’ homes.

The changes in students’ attitudes toward marijuana were highlighted last month by findings from the National Institutes of Health’s annual Monitoring the Future Survey, a nationally representative study of teenagers’ drug use and attitudes toward drugs.

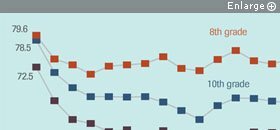

In 2013, 39.5 percent of 12th grade respondents said they viewed regular marijuana use as harmful, a drop from 44.1 percent the previous year and a steep decline from 72.5 percent 20 years earlier, the study said. Among 10th graders, the figure dropped from 78.5 percent in 1993 to 46.5 last year. For 8th graders, it went from 79.6 percent to 61 percent.

While federal researchers saw declines in teenagers’ use of many of the drugs the survey tracks, including alcohol and cigarettes, they saw an increase in marijuana use, they said. That use could continue to grow if young people’s attitudes keep shifting, researchers said.

“We’ve seen, in various historical periods, a strong correlation between changes in an attitude toward a drug and patterns of use,” Lloyd D. Johnston, the report’s lead investigator, said in a Dec. 18 conference call on the results. Of the seniors surveyed, 6.5 percent reported daily marijuana use in 2013, compared with 6 percent in 2003 and 2.4 percent in 1993. Nearly 23 percent of the seniors reported using the drug in the preceding month, compared with 15.5 percent in 1993. And 36.4 percent said they had used it in the past year, up from 26 percent in 1993.

Among 10th graders, 4 percent reported daily marijuana use, compared with 1 percent in 1993; 18 percent said they’d used it in the past month, compared with 10.9 percent in 1993; and 29.8 percent said they’d used it in the past year, compared with 19.2 percent 20 years ago. And 12.7 percent of 8th graders said they’d used marijuana in the year preceding the survey, versus 9.2 percent in 1993.

The 2013 survey was administered on paper to 41,765 students in grades 8, 10, and 12 in 389 public and private schools around the country.

Noting Progress

The research also showed some positive downward trends. Of 12th grade respondents, 39.2 percent reported using alcohol in the month before the survey, compared with 48.6 percent in 1993; and 16.3 percent reported smoking a cigarette in the previous month, compared with 29.9 percent in 1993.

Teenagers’ use of illicit drugs excluding marijuana, such as cocaine, crack, and heroin, has remained relatively constant over the last 20 years, with a slight increase in usage rates at all grade levels in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In 2013, 8.4 percent of surveyed seniors reported use of an illicit drug other than marijuana in the previous month, compared with 7.9 percent in 1993.

The percentage of survey respondents who said they saw “great risk” in regular marijuana use has declined sharply since 1993. Experts link the trend to the growing movement among states to legalize marijuana use.

SOURCES: Monitoring the Future survey, National Institutes of Health

But federal officials focused much of their discussion on marijuana in unveiling the findings.

The shifts in attitudes toward marijuana follow changes that have eased state marijuana laws. Since 1996, 20 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws that allow marijuana use for medicinal purposes, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. They include Colorado and Washington, which also approved measures allowing recreational use of marijuana in 2012.

State medical and recreational marijuana laws, which conflict with a federal prohibition on the drug’s sale and use, place varying restrictions on marijuana possession.

Proponents of nationwide marijuana legalization said it is wrong for federal officials to attribute teenagers’ increased use of the drug to legalization campaigns, and they emphasized their support for prohibiting marijuana use below age 21.

“It’s very similar to the way that we deal with alcohol,” said Morgan E. Fox, a spokesman for the Marijuana Policy Project, a Washington, D.C., group that supports legalization efforts. “Parents can drink around kids and are able to educate them that this can be an unsafe behavior. Parents should be able to do the same with marijuana.”

Legalizing marijuana would allow states to regulate and better control its use, Mr. Fox said.

‘Broken Promises’

But R. Gil Kerlikowske, the director of the federal Office of National Drug Control Policy, said many successful medical-marijuana efforts have “broken promises” to voters by implementing ineffective controls that haven’t prevented minors from obtaining the drug improperly.

Of marijuana-using 12th graders living in states with laws allowing medical use of the drug, 34 percent said they had obtained the drug with someone else’s prescription, and 6 percent said they have prescriptions of their own, the survey found.

The conflict between federal authorities and legalization advocates is increasingly making its way into family conversations and opening up rifts in attitudes between educators and students, according to drug experts.

Because most decisions about drug education efforts are made by districts, it is difficult to detect curricular trends in how marijuana is discussed in states with relaxed laws, representatives of those states’ education departments said. But the leaders of some of the nation’s most popular school drug-abuse-prevention programs said they have not changed their approaches, despite shifts in state laws surrounding marijuana legalization.

Even before recent legalization efforts, anti-drug curricula had trended away from exhorting students to avoid taboo substances and toward a social and emotional approach that teaches students to assess what substances are drugs and the consequences of using them, said Michael L. Hecht, a communications professor at Pennsylvania State University. He wrote the Keepin’ It Real curriculum used by D.A.R.E., a widely used Los Angeles-based provider of drug-abuse-prevention education.

“It’s a move toward developing healthy, effective people,” Mr. Hecht said. “When you have those kinds of people, they make good decisions of all types.”

Potential for Harm

While some advocates see little harm in marijuana use for adults, federal officials say that it is still necessary for schools to emphasize abstinence from the drug, and that, to be effective, those efforts should be age-sensitive, comprehensive, and carried out over multiple years.

Chemicals in marijuana bond to cannabinoid receptors in the brain, blocking its normal functions, medical experts said. The teenage brain, which is still developing, has more cannabinoid receptors than the adult brain, and those receptors are concentrated in parts of the brain that regulate memory, problem-solving, and learning, said Dr. Nora Volkow, the director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, a federal research institute based in Bethesda, Md.

Weakening the brain’s ability to retain and process information can rob students of crucial learning time and slow students’ academic attainment, she said.

“Adolescents are more sensitive to the effects of the drug on the brain because the brain is still developing,” Dr. Volkow said.

Mr. Hecht said that skilled drug-abuse-prevention educators will adapt classroom conversations to the concerns of students, and that the same principles that apply to other drugs apply to marijuana, regardless of its legal status.

“Remember that the two most frequently used drugs are alcohol and tobacco, and they’re not legal for the kids in any of the states,” he said.