U.S. 15-year-olds scored above average on a first-of-its-kind international assessment that measured creative problem-solving skills.

However, their mean scores were significantly lower than those earned in 10 of the 44 countries and economies that took the Program for International Student Assessment, or PISA, 2012 problem-solving test.

The assessment, which was the subject of an Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development report released on April 1, defined creative problem solving as the ability to “understand and resolve problem situations where a method of solution is not immediately obvious.”

Worldwide, a representative sample of 85,000 15-year-olds took the computer-based exam, including 1,273 U.S. students in 162 schools.

The Paris-based OECD introduced the exam based on the belief that today’s high school students will enter an economy in which on-the-job problem solving has gotten progressively more complex because computers have replaced many of the human employees whose jobs once consisted of completing simple tasks.

U.S. students performed just above the international average on the new Program for International Student Assessment problem-solving test.

SOURCE: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

“In modern societies, all of life is problem solving,” states the report.

It is the fifth of six OECD reports on the 2012 assessment, which also tested mathematics, reading, and science, and collected information on students’ communities, lives, and schools. “Complex problem-solving skills are particularly in demand in fast-growing, highly skilled managerial, professional, and technical occupations,” the report says.

Range of Scores

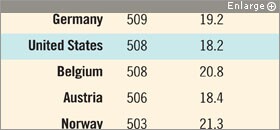

With an average score of 508 points, U.S. students exceeded the 500-point average on the exam, in which countries’ mean scores ranged from a low of 399 (Columbia) to 562 (Singapore). This meant they performed on par with students in England, Estonia, France, Netherlands, Italy, the Czech Republic, Germany, Belgium, Austria, Norway, and Ireland.

Singapore, Korea, and Japan earned the highest scores. In those countries, about one in five students was able to solve the most complex problems, compared to the international average of one in nine.

Heinz-Dieter Meyer, an associate professor of governance, education, and policy at the State University of New York at Albany, said the scores raised questions for him because these nations are not necessarily known for creativity. “Educators may be surprised to see that the results of the new study again list ‘the usual suspects'—Singapore, Korea, and Japan—ahead of everyone else, even though we know from a wealth of sociological and anthropological studies that the cultures in these countries reward conformity above all,” he said.

Other countries that earned significantly higher scores than the United States were Macao, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Chinese Taipei, Canada, Australia, and Finland.

Content and Creativity

U.S. performance was especially strong on tasks designed to measure interactive problem solving, which requires students to find some of the information they need on their own. For example, one interactive task on the exam required students to explore the buttons of an MP3 player on their screen in order to correctly respond to questions about how to use the device.

By contrast, a “static task” provides all the information upfront. In one static task that appeared on the exam, students were given a list of rules regarding the seating preferences of guests invited to a birthday party and then asked to sit them around a table, according to these rules.

The ability to excel in interactive problem solving suggests that “students in the United States are open to novelty, tolerate doubt and uncertainty, and dare to use intuition to initiate a solution,” according to a report released with the results.

“We believe probably that has to do with the way mathematics or reading or science is taught in the United States, especially when you compare that with how it is taught in other countries,” said Pablo Zoido, an analyst with the OECD’s PISA office in Paris. “We think problem solving, or teaching through problem solving, is more developed in the United States than it is in other countries.”

U.S. students also performed better on problem solving than on mathematics, meaning that their problem-solving skills exceeded those of students in nations with similar performance in math. Even though they scored above average on problem solving, U.S. students scored slightly below average in mathematics in 2012.

However, U.S. students lagged behind those in the highest-performing nations when it came to tasks that required them to “select, organize, and integrate the information and feedback received in order to represent and formulate their understanding of the problem,” according to the OECD report.

In addition to presenting results for all students who took the test, the PISA report also broke out average scores for subgroups. In the United States, girls’ scores equaled those of boys even though, internationally, boys outscored girls by 7 points. Exceptions to that trend were Australia, Finland, and Norway, where girls outperformed boys.

However, as in other nations, more U.S. boys than girls earned extremely high scores on the exam. Across all participating countries, there were an average of three top-performing boys for every two top-performing girls.

Students with immigrant backgrounds scored significantly lower than non-immigrants in the United States, as they did in most of the other nations that participated in the exam. Finally, as in the rest of the world, the relationship between socioeconomic status and assessment results was weaker in problem solving than in mathematics.

Reopening Debate

Michael J. Feuer, the dean of the graduate school of education and human development and a professor of education at George Washington University in Washington, suspected that these latest PISA results could play a prominent role in discussions of how schools prepare students for the world of work.

“I anticipate that the results will reopen a longstanding and important debate about the general versus specific nature of ‘problem-solving skills,’ and about where (school, work, family) and when (at age 15, during the pre-K years, throughout the lifespan) those skills can and should be formed, especially in an era when skill demands are changing because of technology and other global economic realities,” he said. However, Mr. Feuer was also concerned that too much might be made of the results of a single test of a single age group.

“Although performance on this test, which is based on simulated problem situations, is perhaps mildly indicative of a more general and long-lasting set of relevant competencies, it would be a mistake to infer that knowledge and skills assessed at age 15 are somehow fixed or predictive of future performance or of ‘success in life,’ ” he continued. “There is abundant research showing that much learning takes place ‘on the job’ or experientially, and that performance on even high-quality simulation tasks on standardized assessments are weak predictors.”