Teacher collaboration is hailed as one of the most effective ways to improve student learning, and one high school in Illinois is often credited with perfecting the concept.

Adlai E. Stevenson High School was one of the first in the nation to embrace what are known as professional learning communities. The school’s focus on teacher teamwork has catapulted it from an ordinary good school to an extraordinary one, advocates say: Among its many accolades, it has been a U.S. Department of Education Blue Ribbon school for four years—one of only three nationwide to achieve that honor. Moreover, as many as 96 percent of Stevenson’s students go on to college. So well known are the learning communities here that each year, 3,000 people visit the school’s sprawling campus 30 miles northwest of Chicago to experience firsthand how its teacher-collaboration model works.

Eric Twadell, the superintendent of Stevenson High, a one-school district, describes the professional learning community, or PLC, as “teachers working smarter by working together.” From the beginning, he said, the idea was not to create something new or different, but simply to foster an atmosphere in which teachers could learn from one another and share their colleagues’ expertise so that, in the end, students would benefit.

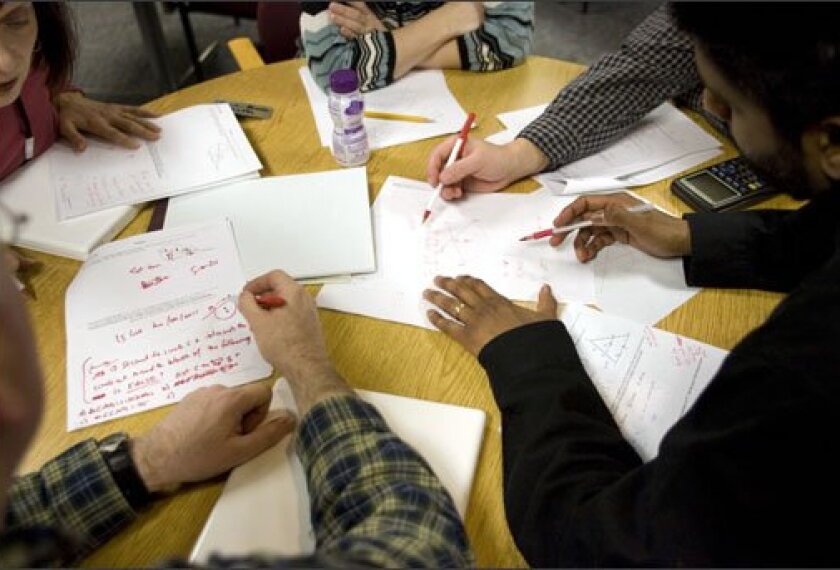

In a professional learning community, each teacher has access to the ideas, materials, strategies, and talents of the entire team. At Stevenson, teachers meet in course-specific, and sometimes interdisciplinary, teams each week to discuss strategies for improvement; craft common assessments, the results of which are analyzed to improve instruction; and brainstorm lesson plans.

Instead of the isolation of their classrooms, they spend their time between classes and before and after school in open office areas where their desks abut those of their course peers. The arrangement ensures that the give-and-take between teacher teams is almost constant.

“Many of the best things we do don’t happen in team meetings,” said social studies teacher Brian Rusin. “The real collaboration happens outside.”

Even professional development at the school is targeted at the teams, and the hiring process for new teachers takes the teams into consideration. Candidates meet the teachers who constitute the teams they’ll be in if hired, in addition to administrators and department heads.

The term “professional learning community” emerged among researchers as early as the 1960s, when they offered the concept as an alternative to the isolation in which most teachers worked. Over the years, more and more schools have adopted PLCs, and the concept has gained wider acceptance in education circles. A broad range of stakeholders, from state education departments to teachers’ unions, sing the idea’s praises.

Several states, including California, Missouri, and New Jersey, incorporate learning communities or collaborative teaching in their professional-development standards.

While it is not clear how many schools actually practice collaborative teaching or have established PLCs, Stephanie Hirsh, the executive director of the Oxford, Ohio-based National Staff Development Council, points out that versions of it can be found at many successful schools.

“You find any high-performing high-poverty school, and you will find elements of PLCs,” Ms. Hirsh said. “You will find schoolwide goals, teachers working together on lesson plans, … all those critical elements that make up a PLC.”

But implementing professional learning communities is challenging. For starters, they require a deep cultural change within the school. Education consultant and author Richard DuFour offers the example of movies about great teaching that usually feature a single teacher making a difference in the lives of his or her students.

“That’s the story we’ve told ourselves about teaching, but now we’re saying we have to collaborate and make a collective effort” to help students succeed, said Mr. DuFour, who was the principal at Stevenson High when it first took steps to set up its PLC in 1983.

At Stevenson, Mr. DuFour said, teachers had some reservations at first, and although local union leaders were cooperative, they had concerns about whether assessments, for example, would be used in a punitive way.

“The beauty of working in isolation and doing your own assessing is that you are buffered from an external source of validation. But here we want you to talk to colleagues, want you to look at common assessments that you and your teammates have developed, and that’s pretty scary initially,” he said. Doing that required a lot of sensitivity and dialogue with teachers early in the process before the cultural change could happen, Mr. DuFour said.

It also took some work to convince the school board. Stevenson, located in a middle-class community, was doing reasonably well in the 1980s, and “there was no sense of crisis, no [No Child Left Behind Act], no state standards,” Mr. DuFour said.

As a result, he said, the initial reaction from the school board was “why should we change things; the results are all right, the community seems to like us. There were no imperatives or sense of urgency.” The first step then, he said, was to start out with an assumption that “we didn’t want to be a good or good enough school, but an exemplary school that lived up to a model of success for every student.”

By now, the culture of coolaboration is so deeply embedded at Stevenson High that even the school’s counselors and administrators are organized in teams, all working in tandem with the teachers’ teams to help students.

Each freshman, for instance, is assigned a support team to monitor his or her emotional well-being and progress in achieving academic goals. Students who fall behind academically are given an extra hour of study time each day and specific intervention, if needed.

Richard DuFour, a consultant who is considered a leading expert on professional learning communities, says educators can enhance the effectiveness of teacher teams by focusing on essential points:

Every Tuesday at Stevenson, classes start 35 minutes later than other days, but teachers arrive early for their team meetings. The teams range in size from three to 20. Some teachers belong to more than one team, but all the school’s 300 teachers are on at least one.

On a recent snow-swept Tuesday morning, French teachers Paul Weil and Agnes Aichholzer make their way into an empty classroom for their meeting. A third team member is on leave.

This morning, Mr. Weil and Ms. Aichholzer strategize on how best to attract new students to courses in French—not an easy job at a school that offers many languages. Other mornings, the team might talk about student progress in their courses, or perhaps, how to better teach a certain aspect of grammar.

“It is our way of gathering and checking in. … We have much better results when we speak to each other and come up with different solutions,” Mr. Weil says.

A few doors down in the 4,500-student school, five members of a math “problem-solving” team are putting their heads together. They talk about different ways of doing problems. Someone wonders if grading tests as a team might be a good idea.

Disagreement occurs sometimes when teachers sit down to brainstorm, but even when that happens, says math teacher Victoria Kieft, they eventually agree on what is in the students’ best interests.

Superintendent Twadell suggests that some dissidence can be good. But while at other schools that might mean a teacher who disagrees will escape to his or her classroom, at Stevenson it means working together through the differences to find common solutions.

All teams identify team norms of interaction—rules that govern behavior. “We work hard to make sure we all get along,” Mr. Twadell said. Teachers on each team choose their leader, who then heads up the discussions and assigns duties to each member.

The culture of teacher collaboration at the school dates back so far that even veterans have long been used to working together, although the format has changed over the years, from meetings in which teachers would just sit down for informal discussions to the present, more structured format, said Dan Larsen, a social studies teacher.

Linda Reusch, a math teacher, said PLCs are just a buzzword. “We have always talked to each other, and not at each other.”

Proponents say one of the most important goals for any school planning to establish learning communities is to tailor them to the school’s specific needs, rather than copying an existing model.

“One of the worries that NSDC has had is that the label is being used for a lot of experiences, from staff meetings to something that we would genuinely call a professional learning community,” said Ms. Hirsh, the staff-development council’s executive director. For instance, she said, she has been at schools with so-called PLCs where the conversation at meetings centered on organizing field trips and managing classrooms or students’ failure to turn in homework.

While all those topics are important, Ms. Hirsh said, the agenda of PLCs needs to be more about examining, for instance, available data on how students are meeting standards and determining what needs to be done to help them succeed through sound lesson plans and strategies.

Members of newer learning communities that have made gains in student achievement agree that while they found learning from the experiences of schools like Stevenson invaluable, they’ve had to create their own versions.

Mike Mattos, the principal of Pioneer Middle School in Tustin, Calif., began the process of setting up teacher teams in his school four years ago, after having done so previously at an elementary school where he had been principal.

“When I came [to Pioneer], I didn’t say that I will start a PLC,” Mr. Mattos said. Instead, he focused the teachers on working together to get the school’s 30 percent of children who were not proficient on state and federal tests to a proficient level. It worked, he said, because the teachers, too, wanted to ensure their students’ success. “Almost every teacher that I have ever worked with joined the profession to help people,” he said.

“Most teachers don’t want to work in isolation,” Mr. Mattos said. “They want to be part of something bigger. They realize that collaboration is good not just for the children, but for the teachers as well.”

At some schools, the collaboration has extended outside school boundaries. At Fargo North High School, for instance, the single French teacher collaborates with the French teacher from the other high school in Fargo, N.D. So do the German teacher and the health teacher.

“The way we think about this is that when teachers collaborate for learning and development, all students benefit,” said Principal Andrew Dahlen.

Mr. Twadell of Stevenson High points out that getting teachers to collaborate does not cost any extra money, nor does it require an enormous investment of time. The most important part, he adds, is to home in on the right questions.

“Schools can begin by organizing teachers into collaborative teams and have them ask the question: What do we do when students don’t learn?” he said. “It will slowly but surely change the culture of the school.”

Coverage of new schooling arrangements and classroom improvement efforts is supported by a grant from the Annenberg Foundation.