Teachers with national certification could spearhead improvement in many of the most challenged schools, but only if policymakers and principals see the complexity of such an undertaking.

That conclusion was reached at a gathering here last week of school and community leaders from four big-city districts with sizable contingents of teachers who have won certification from the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards.

Cautioned Lori Nazareno, a teacher with the credential at Myrtle Grove Elementary School in Miami, “We can’t expect national board-certified teachers to parachute into the middle of a school that is saying, ‘Save me!’ ” and have success.

Chicago leaders convened the meeting jointly with the Arlington, Va.-based NBPTS to consider how the district can best use its existing crop of 380 nationally certified teachers while encouraging more of its 27,000 teachers to seek the credential. The district has set an ambitious target of 1,200 board-certified teachers by 2007.

Arne Duncan, the chief executive officer of the 435,000-student district, calls the endeavor “a core strategy” for improving the city’s schools. It has drawn $2.4 million from the Chicago Public Education Fund, a “venture capital” philanthropy that raises money in the local business community.

At last week’s meeting, which was the brainchild of the fund, Chicago leaders drew ideas from the Charlotte-Mecklenburg, N.C.; Los Angeles; and Miami-Dade County, Fla., districts, where the proportions of board-certified teachers are greater than in Chicago but still under 1 percent of the total in each of the districts.

Bonuses Targeted in California

In one sense, the gathering reflected the widespread conviction that high-caliber teaching holds the key to raising student achievement and closing gaps between poor and minority children and their more affluent white peers. But in another, it underscored perhaps the greatest obstacle to making that insight pay off: Skilled and experienced teachers have long been underrepresented in schools serving disadvantaged children.

Many at the meeting said change at struggling schools can’t depend solely on the efforts of highly accomplished teachers. Even if financial incentives and high hopes can get them into such schools—or can cultivate them there—such teachers will not stay without a supportive working environment. Nor will they be effective unless they are groomed for leadership and given opportunities to influence the quality of teaching and administration at the school.

Currently, the more than 40,000 teachers nationwide who have earned the advanced certification through testing and a year of documented self-reflection are less likely than their counterparts without the voluntary national credential to be teaching in schools serving poor and minority students, according to a paper by Barnett Berry and Tammy King of the Southeast Center for Teaching Quality in Chapel Hill, N.C.

The exception is in California, which abolished an across-the-board bonus for teachers who earn the certification but kept a $20,000 award paid out over four years for those working in low-performing schools. Los Angeles also offers a bonus of up to 15 percent of a teacher’s salary, half in exchange for doing such work as mentoring other teachers.

Even within the four urban districts that were the focus of the meeting here, board-certified teachers overall are not at the low-performing schools that the organizers say need them most. Partly that’s because such schools are often hard places to earn the credential, which typically requires hundreds of hours of work. It’s also that accomplished teachers are unwilling to stay or move to troubled schools where their chances of success seem remote, Mr. Berry and others stressed.

“I see a pattern of a lot of people who achieve [national-board certification] as a way to move to a better school or one that doesn’t have the problems their current one has,” said Victor Harbison, a Chicago teacher with the certification who attended the meeting.

Money’s Not Enough

Even substantial money doesn’t make the job of luring teachers to a struggling school much easier, said Nancy Webber, another board-certified teacher at the gathering. Ms. Webber moved to a low-performing high school in the 122,000-student Charlotte-Mecklenburg district this year to be part of a pilot project that uses teachers like her to help keep other teachers from quitting.

Ms. Webber estimates that the financial incentives available to teachers in the district’s lowest-performing schools next year will go as high as $15,000, part from the state and part from the district. “I’m out grassroots-recruiting big-time, and I’ve got two,” she said, who are willing to move to a school in her project. She considers her experience “proof positive money is not the issue.”

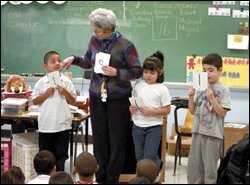

Or it’s at least not the only issue. During one panel offering, three Miami teachers with national certification discussed what drew them to Myrtle Grove Elementary School, a low-performing school that gets special help under a new program in the 363,000-student school system. They cited the chance to work in a building with like-minded colleagues and a principal who grants them the freedom to teach in the best ways they know how.

Michelle Ivy, who moved from a high school to work at Myrtle Grove Elementary, decried the idea of forcing teachers with the advanced credential into low- performing schools, a power that the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school board is considering. “Some teachers do not belong in [such] schools, and they’ll leave,” she argued.

Barbara L. Johnson, the principal at Myrtle Grove, said principals need to understand the certification process. “Some principals have no idea what [board-certified teachers] can do,” she said.

Leadership Isn’t Automatic

At the same time, teachers and researchers cautioned that accomplished teaching does not automatically translate into leadership, without which a board- certified teacher’s influence remains largely confined to a classroom or two. Teachers who would help colleagues raise the level of teaching need to have the confidence born of knowing, for example, how adults learn best.

Districts must also help map out ways to best use the teachers. In Charlotte-Mecklenburg, for instance, which has among the highest density of teachers with the credential in the nation—almost 750 among some 7,700 teachers—the district has paid for a full-time coordinator of activities (herself a board-certified teacher) involving the teachers since 1998. As a result, teachers with the credential are involved in curriculum development, research, professional development, and service on committees at various levels.

Though the 10-year-old credential is not without its critics, who claim it has not proved itself as a way for teachers or schools to improve, many applaud an attempt to get more of those teachers into the most challenged schools.

“I think there’s tremendous value in bringing in talent to dysfunctional schools,” said Kate Walsh, the president of the Washington-based National Council on Teacher Quality, which advocates better teaching and more flexible entry into the field. “There are plenty of heroes in those schools who stick it out, but too often, they are a revolving door for teachers.”