Most school districts wait for leadership talent to emerge by posting job openings and then seeing who applies. But at least some districts and charter-management organizations are starting to take a more active role in identifying and supporting future principals earlier in their careers.

This more systematic approach to leadership development, known as “succession planning,” has long been common in business, the military, and other fields. Now, a combination of factors is causing school systems both here and abroad to take succession planning more seriously.

“There’s a perfect storm in the whole education profession, including in leadership—a massive demographic turnover, where the boomer generation is leaving and there’s no intermediary generation immediately ready to take over,” said Andrew Hargreaves, a professor of education at Boston College and the co-author of the 2006 book Sustainable Leadership, with Dean Fink.

The increasing expansion of the principal’s role and responsibilities, and the changing job expectations of the younger generation, Mr. Hargreaves said, mean fewer and fewer people are ready or willing to take on the leadership challenge.

Succession planning “is essential to widen the applicant pool for school leadership and increase the quantity and quality of future school leaders,” argues a report to be released this week by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development comparing leadership policies and practices in 22 countries. “It is a way to counteract the principal shortages that are looming in many countries, and to ensure that there is an adequate supply of qualified personnel to choose from when the incumbent leader leaves the position.”

Yet the study, “Improving School Leadership,” found that “insufficient attention is being given to identifying and fostering potential future leaders in most countries.”

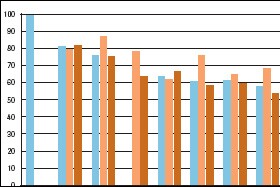

In 2004, according to data from the federal Schools and Staffing Survey, school leaders were typically older than those working a decade earlier. Over the course of a decade, the median age of principals rose from 48 to 51.

** Click image to enlarge

SOURCE: Editorial Projects in Education Research Center

Here in this country, districts and charter-management organizations have waded into succession planning for a variety of reasons, ranging from an aging principal workforce, to rapid enrollment growth, to concerns about the quality of job candidates.

“Districts are large, complex organizations,” said Frances McLaughlin, a senior director with the Los Angeles-based Broad Foundation, “and the care with which they are thinking about building redundancies into their leadership, and planning for natural succession as people retire or move on, is not happening with the same regularity and forethought as it does in comparably complex organizations.”

“Having a plan for the succession of the actual people,” she added, “is a good way to ensure that your cultures, values, and mission stay intact.”

About five years ago, Delaware policymakers realized that more than half the state’s principals and assistant principals would be retiring in the next five years. So the state formed a task force to look at leadership recruitment, retention, and working conditions. One of its recommendations was to work with districts on succession planning.

In collaboration with Development Dimensions International, which helps Fortune 500 companies identify and train talent, the state designed a one-day training session for districts and charter schools, and encouraged them to apply for $10,000 mini-grants, starting in 2004.

“Currently, we have about 12 districts and two charters that have what we call official succession plans on how they’re going to identify their talent,” said Jackie O. Wilson, the associate director of the Delaware Academy for School Leadership, based at the University of Delaware.

One of those districts is the fast-growing 8,300-student Appoquinimink school system. Concerned that it needed to generate a constant supply of new leaders, the district created the Appoquinimink Aspiring Administrators program four years ago and encouraged teachers with at least three years of experience in the district to apply.

The first year, 31 teachers volunteered to attend evening classes led by district administrators. Out of that group, the district identified 18 people with “high potential,” who participated in an additional year of book studies, conversations, and group learning once or twice a month. Participants also agreed to serve on districtwide committees and to attend school board meetings.

School leaders who are newer to the job are entering the principalship at an older age, and with more extensive leadership training and experience in administrative roles, than those who have been principals for more than 10 years, federal survey data show.

** Click image to enlarge

SOURCE: Editorial Projects in Education Research Center

“We tried to involve them in all phases of what the district does to deliver a quality education with fidelity,” said Marion E. Proffitt, the assistant superintendent. Of the district’s 10 principals, five have come through the program, as have six assistant principals. “They’re able to be what I consider first-day productive,” said Ms. Proffitt. “They already know the district; they’ve been a part of it.” Similarly, in Fairfax County, Va., demographic factors set off alarm bells.

“About seven years ago, we found that we would be losing 70 percent of our sitting administrators in five years,” said Andrew M. Cole, the director of leadership development for the 165,000-student district in the Washington suburbs. While a strong bench of assistant principals was coming up behind them, he said, they were in the same age cohort.

So the district decided to focus its attention on growing a pool of future leaders who would be ready and able to step in. With a grant from the New York City-based Wallace Foundation, which also supports coverage of leadership issues in Education Week, the district created an administrative-intern program that takes teacher leaders out of the classroom for a year and places them with a mentor principal. To be eligible, teachers have to be within 12 hours of earning an administrator’s license or already have one. Interns meet twice a month for classes and during the summer. So far, about 150 teachers have completed the program, and 40 are employed as principals.

“I think that every school district should have this program, or one like it,” said Nardos E. King, a former intern who is the principal of the 1,775-student Mount Vernon High School. “Looking back, it was the best possible way to prepare me to actually step into this job. I had a whole year to ask all the questions that I needed to ask, to observe many different leaders, plus get a whole lot of professional development.”

In collaboration with the state and area universities, the Fairfax County district also devised an accelerated, yearlong route to principal certification for which the district pays tuition. So far, 39 people have completed the program, and all passed the licensing test for administrators on their first try.

Developing the leadership talent of people who already know the local context and culture may be particularly important for charter schools. “We have come to the conclusion now, after nine years, that we do our best work for our kids when we hire from within, and we make a plan to grow the leadership in advance,” said Don Shalvey, the co-founder and chief executive officer of Aspire Public Schools, a charter school network based in Oakland, Calif.

“We have retained 100 percent of the principals who we grew from within the organization, and we’ve retained 40 percent of the ones we brought in from outside. We found out it’s far more important to understand the culture of the organization from the ground up.”

Across the globe, nations are struggling to address the imminent retirement of the majority of school principals. In the 2006-07 school year, half or more of public school principals were age 50 or over in all but three of the countries in a recent study conducted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

** Click image to enlarge

SOURCE: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

Aspire now prepares its own principals in cooperation with San Jose State University. The network provides the faculty members for the two-year program; candidates pay reduced tuition and earn an administrative credential and a master’s degree. Of the 38 people in the first two cohorts, five are now Aspire principals.

Similarly, the New York City Center for Charter School Excellence, a nonprofit support organization, began its Emerging Leader Fellowship program—which prepares charter school teachers to become assistant principals—after seeing so many schools struggle to fill leadership roles. As charter schools grow in size, said Glenn J. Liebeck, the director of school leadership development for the center, they often take their best teachers and simply promote them.

“Sometimes, when it doesn’t work out, not only do you lose your best teacher,” he said, “you still have to rehire for that assistant-principal job.”

The fellowship reduces teachers’ workloads by 10 percent to make room for a practicum at their home schools and a seminar at the center taught by expert practitioners. “Our plan is to train teachers to become assistant principals,” Mr. Liebeck said. “Hopefully, they’ll be assistant principals for two or three years before they go open up a school or assume a head-of-school role.”

At least some large districts are starting to develop their own talent pipeline.

In 2006, the Long Beach, Calif., district, with 90,000-plus students, faced its first shortage of applicants for principal vacancies, with more openings on the horizon. So it created three programs for people aspiring to become school leaders: a series of three, full-day workshops for people interested in becoming assistant principals; a five-day workshop for assistant principals who want to become principals, with an added five days of job-shadowing a principal, geared to their individual needs; and a program for current teacherleaders, offered in conjunction with California State University-Long Beach, that provides a fast-track toward an administrator credential. University faculty members and district administrators co-teach the latter.

“It’s a huge shift in the last two years over what we were doing,” said Kristi A. Kahl, the program administrator for leadership development. “It’s really exciting because we’re identifying these stars. We’re going back into the pipeline and saying, ‘You have the potential, and we’re going to work with you.’ ”

Starting next fall, the Long Beach initiative will include a yearlong apprenticeship as a principal-in-training, with support from the Broad Foundation. As part of instituting the programs, the district also revamped its selection and evaluation process for school leaders to ensure it was really identifying people with the desire and potential to lead.

Susan Schaeffler, the executive director of KIPP DC, poses with her children Sam, Jack, and Sarah Ettinger.

From her first day on the job in 2001, Susan Schaeffler, who founded the first Knowledge Is Power Program school in the District of Columbia, has hired teachers with an eye to their leadership potential. The strategy paid off when teacher Sarah Hayes became the school’s vice principal and then its principal when Ms. Schaeffler gave birth a few years later.

The Gwinnett County, Ga., district dived into succession planning to cope with rapid enrollment growth. The district has ballooned from some 36,000 students in 1983 to about 155,000 today.

“We looked at the number of applicants that we were receiving; we looked at where they were being prepared and how they were being prepared; and we looked at the quality of the candidates,” said Glenn E. Pethel, the executive director of leadership development for the district, located in the Atlanta-metro area, “and we made a very conscious decision that we had to be involved with the universities, to the extent that we could, in the preparation of new leaders.”

The district partners with five universities, ranging from the University of Georgia to the private Mercer University, to prepare future leaders. Candidates for the programs apply jointly to one of the universities and the district. University and district personnel sit together and review applications for cohort groups, and they both teach courses.

Mr. Pethel said about 75 teachers are involved in the programs, and the district’s goal is to have 100. “We’re not sitting back, crossing our fingers, and hoping that the right people show up at the right time,” he said.

The district also set up an aspiring-principals program for assistant principals who meet certain eligibility criteria. The yearlong program includes 12 days of formal coursework developed by the district, extensive out-of-class assignments, and a residency component. The first group—37 administrators—graduated in December. The district also assigns every first- and second-year principal and assistant principal a mentor to provide ongoing support.

Mr. Hargreaves of Boston College cautions that while a growing number of districts have paid attention to increasing the supply of future school leaders, they may need to think more broadly still.

“The corporate strategy is increasingly to move from succession planning, which is how you replace one person with another, to succession management, which is how you create big pools of people from which many leaders can come,” he said. “And that means creating lots of opportunities for leadership throughout the school, not just one or two favorite children who advance ahead of the rest. That means massive changes in school leadership to operate in a more inclusive way.”

Coverage of leadership is supported in part by a grant from The Wallace Foundation, at www.wallacefoundation.org.