When I first met “Juan,” then a 2nd grader, he knew about half of his consonant sounds and none of his vowels. I was a new K-5 special education teacher at the time, now more than a dozen years ago, and his initial reading assessment results looked pretty similar to those of the other 21 kids I was servicing.

Juan was a handful—brimming with mischief and vigor. He’d been diagnosed with a specific learning disability in reading and placed in special education early on. I figured we had a long, hard slog ahead of us.

I was, in some ways, quite wrong.

Juan picked up the individual letter sounds and digraphs I introduced in no time. He began decoding shorter, then longer, words and reading books with the sounds he’d learned. The reading gains were coming fast for a student who’d stagnated for two years prior.

It wasn’t my pedagogical ability making the difference—my lagging classroom management and unsteady math instruction made that quite clear. But I did have a secret weapon of sorts. Before coming to the public school, I’d spent a couple years working at a tutoring center that taught, among other things, an intensive phonics program to students with reading difficulties. I’d had dozens of hours of training in several different research-based reading programs, and taught close to 100 students how to read.

At the time, I figured most early-reading teachers had, at some point, had similar cognitive science-based training.

But as results from two new nationally representative surveys show, that’s not the case.

In preparing this reporting series, the Education Week Research Center surveyed about 670 K-2 and special education teachers and 530 education professors who teach reading courses. The findings—among the first to look at teacher and teacher-educator knowledge and practices in early reading across the country—tell an illuminating story about what’s happening in classrooms, including what teachers do and don’t know about reading and where they learned it.

It’s all part of a larger project we’ve taken on this year called Getting Reading Right, which explores the challenges teachers face in bringing cognitive science to the classroom. We think it’s timely, given that recent scores on the “nation’s report card” show that just 35 percent of 4th graders are proficient readers—and that the gap between low and high performers has grown.

Our new survey showed that 75 percent of teachers working with early readers teach three-cueing, an approach that tells students to take a guess when they come to a word they don’t know by using context, picture, and other clues, with only some attention to the letters.

Similarly, more than a quarter of teachers said they tell emerging readers that the first thing they should do when they come to a word they don’t know while reading is look at the pictures—even before they try to sound it out.

And yet, as the research primer in this report details, those techniques aren’t backed by science. They’re methods employed by struggling readers; proficient readers attend to the letters.

The survey also showed that 1 in 5 teachers confuse phonemic awareness with letter/sound correspondence. Only about half knew that students can demonstrate phonemic awareness by segmenting the individual sounds in a word orally.

We also asked teachers about their philosophy of teaching early reading. Sixty-eight percent said “balanced literacy,” while 22 percent chose “explicit, systematic phonics (with comprehension as a separate focus).”

Getting Reading Right - An Education Week Online Summit

Balanced literacy, as many will point out, has no single definition—though there’s agreement among most balanced literacy advocates that comprehension and immersion in authentic texts are key. Yes, students need some phonics, but not too much or they’ll become disengaged, the thinking goes.

And yet a multitude of studies over many decades have shown that systematic, explicit phonics is the most effective method for teaching early readers. And a much-validated framework, known as the Simple View of Reading, says that reading comprehension is reliant on both decoding and language skills. A student cannot understand a text that he cannot accurately decode.

In all, the survey points to a willingness among teachers to spend time on phonics—the majority who responded said they devote 20 to 30 minutes a day to it. But that’s coupled with a commitment to practices, such as cueing, that research has shown can actually counteract good phonics instruction by encouraging students to look away from the letters on the page.

So where are teachers learning what they know about the foundations of reading?

According to the survey, most of this training is happening on the job. Teachers were most likely to say they learned what they know about reading from professional development or coaches in their district (33 percent), or from personal experiences with students (17 percent). Our reporting bears this out, too—a culture of reading instruction is often passed from classroom to classroom. Teachers learn what to do from trusted colleagues and cherished mentors.

Fourteen percent of teachers surveyed said they learned to teach reading from their school-provided curriculum. Teachers also listed the instructional materials they’re using for reading, and an analysis of the top five shows they often push cueing strategies and fail to implement phonics in a systematic way.

Teachers were less likely to say they learned what they know about reading from their preservice training.

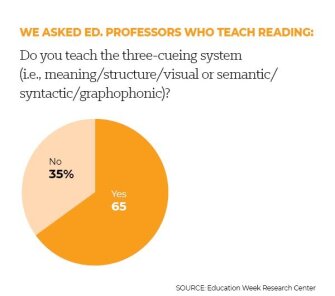

Still, a look at the survey results from professors offers insight into where some ingrained literacy practices come from. Nearly 6 in 10 professors said their philosophy of teaching early reading is balanced literacy. And ideas about teaching reading are coming from the professors themselves—most said they have some or complete control over the syllabus for their early reading courses.

Most professors (86 percent) said they model how to teach phonics in their classes. But like the teachers, about 1 in 5 professors confused phonemic awareness with letter/sound correspondence. And 1 in 10 professors could not correctly identify that the word “shape” has three phonemes.

Like the teachers surveyed, the education professors seemed to hold sometimes dissonant beliefs about how reading should be taught. Eighty-one percent of professors disagreed with the statement that “most students will learn to read on their own if given the proper books and time to read them.” But more than half of professors agree that “it is possible for students to understand written texts with unfamiliar words even if they don’t have a good grasp of phonics,” indicating a lack of familiarity with the Simple View of Reading.

Teachers want what’s best for their students—it’s simply not possible to put in the hours and sweat needed for the job if you don’t. But wanting that and having the training, materials, direction, and support to provide it are not the same.

I won’t go so far as to say Juan was misdiagnosed with a learning disability—he did struggle in many ways. But I do often wonder how his trajectory might have changed if he’d finished his elementary years having never been exposed to a systematic, science-based reading program—a possibility we know is very real for many children.

Data analysis for this article was provided by the EdWeek Research Center. Learn more about the center’s work.